Search

Technological advances, such as telescopes and microscopes, have enabled us to enlarge our world, up and down. Microbes are an example of the two scales, small and large.

We now have more information than ever about nutrition. But, at the same time, we have great difficulties to identify reliable information and, above all, to understand the limitations of science to answer so many of the questions that we make ourselves about how the food we eat and the food we avoid affects our health.

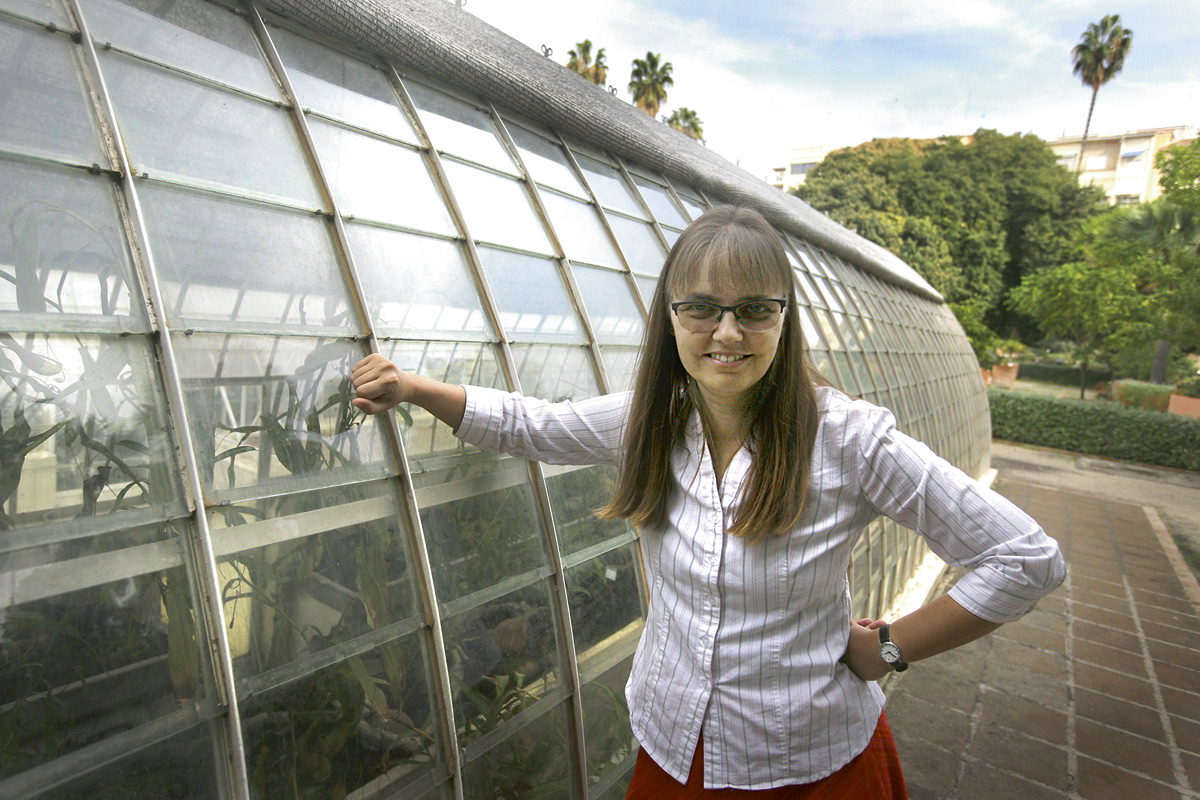

Interview with Hanna Kokko, full professor of Evolutionary Biology at the University of Zurich.

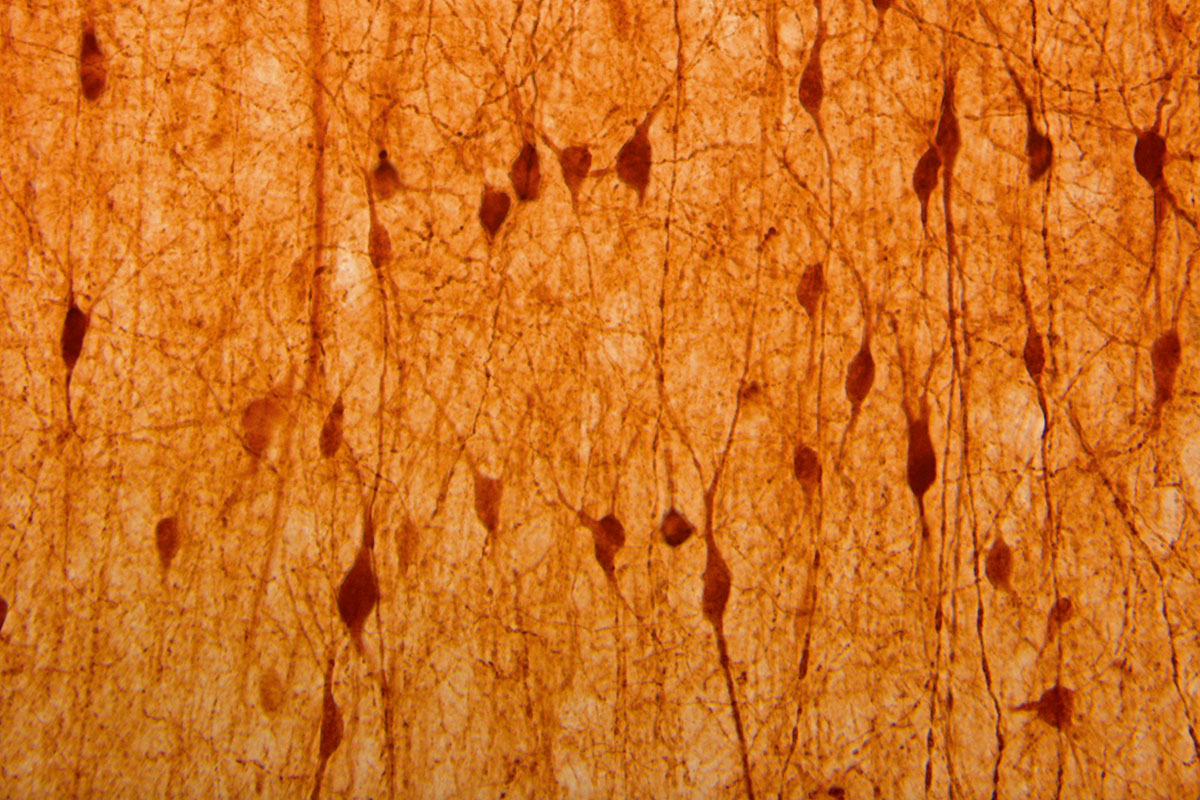

For a correct functioning of the brain, it is essential that the number of neurons is the appropriate one: neither more nor less.

Since Mètode's first issue appeared in 1992, the journal has become a benchmark within the publications devoted to the communication and dissemination of science.

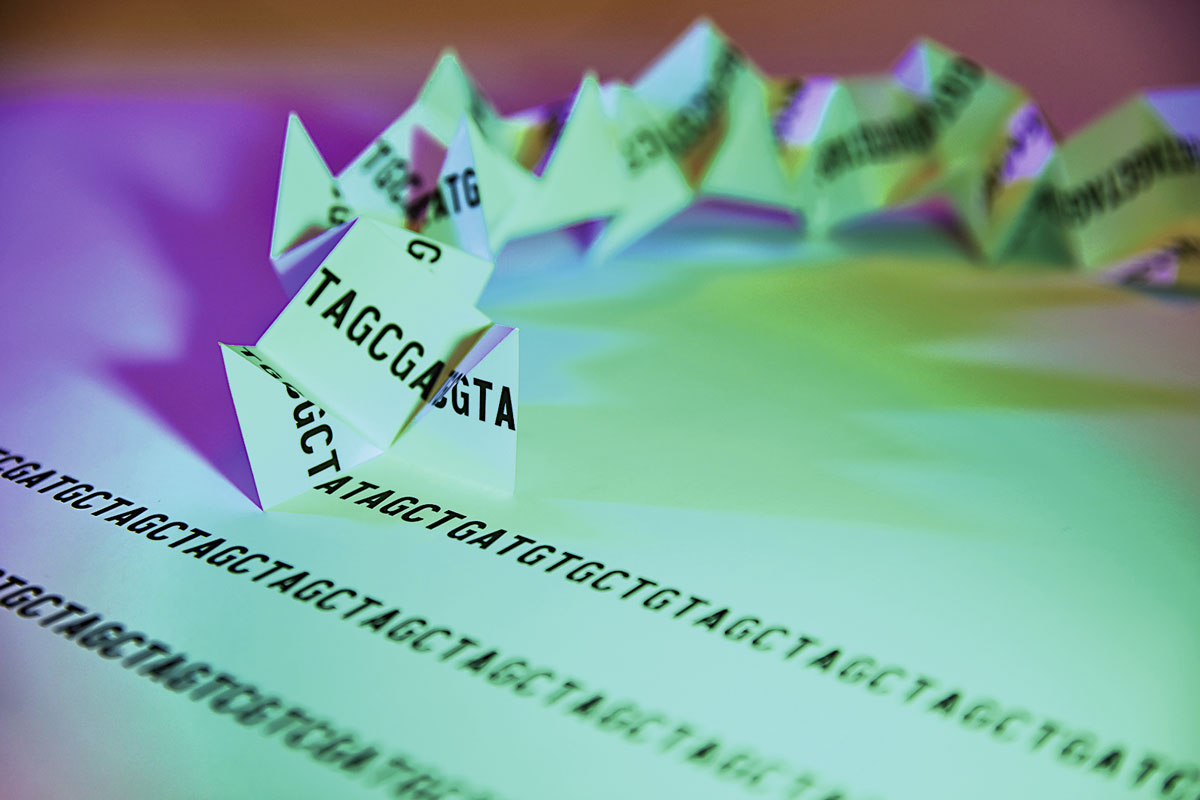

It is clear that the term synthetic biology raises expectations, but it is no less true that it also causes concern. This article starts with a critique of the identification of cells as machines and discusses the current scope of synthetic biology and efforts to standardise it. We also outline some of the social implications of attempts to manufacture life.

Energy is the blood that moves today’s society and is one of the factors that has decisively contributed to improving humanity’s quality of life. This paper addresses the potential challenges and opportunities in the development of global energy systems, emphasising how deeply interconnected the energy and climate debates are.

The following reflections are based on the premise that individual and social life is open to a number of possibilities, among which we can find digitalisation.

We are living through a crisis which we call Anthropocene. Even though we study their ecological impact, their causes are social: the destruction of cultures and biodiversity is the heritage of colonialism, although it is now following different paths or being played out by different actors.

Guaranteeing access to food for a growing human population – based on sustainability criteria and in the face of the climate change threat – is the main challenge for twenty-first-century agriculture. The solutions are inevitably complex, require a variety of coordinated measures, and are dependent on the development of technologies.

Jorge Wagensberg felt as an alien – an intruder – in a world that has lost the taste for slow and reasoned conversation. A society in which humans, trapped by fear of the future, uncertainty and volatility, too often renounce to become what we are.

Can humans control the future evolution of our species? Based on current knowledge in genetics, one can infer and extrapolate what may happen in the near future. After all, if we are to predict the future, we must first understand the foundations of our present.

Adults and older people have most likely always wondered how the young will manage to survive in the world they are left with, and at this point in history, this is a central question in our debates. In order to resolve it, we must resort to one of the main tools we have devised to try to understand the world we live in, the one we call science.

On the occasion of the 100th issue of Mètode, we present reflections on some of these challenges, such as food and energy production, the processing of information, genetic modification, or synthetic biology.

«If we do science but we are not able to disseminate it, we are only halfway there»

Interview with M. Vicenta Mestre

Interview with M. Vicenta Mestre, Principal of the University of Valencia

We do not know what the science of future will bring, but we can assess that the mythical creation of Zarathustra survives.

I confess I have a small problem, which I suspect I share with many fellow scientific disseminators: more and more every day, my interests do not coincide with the interests of my readers.

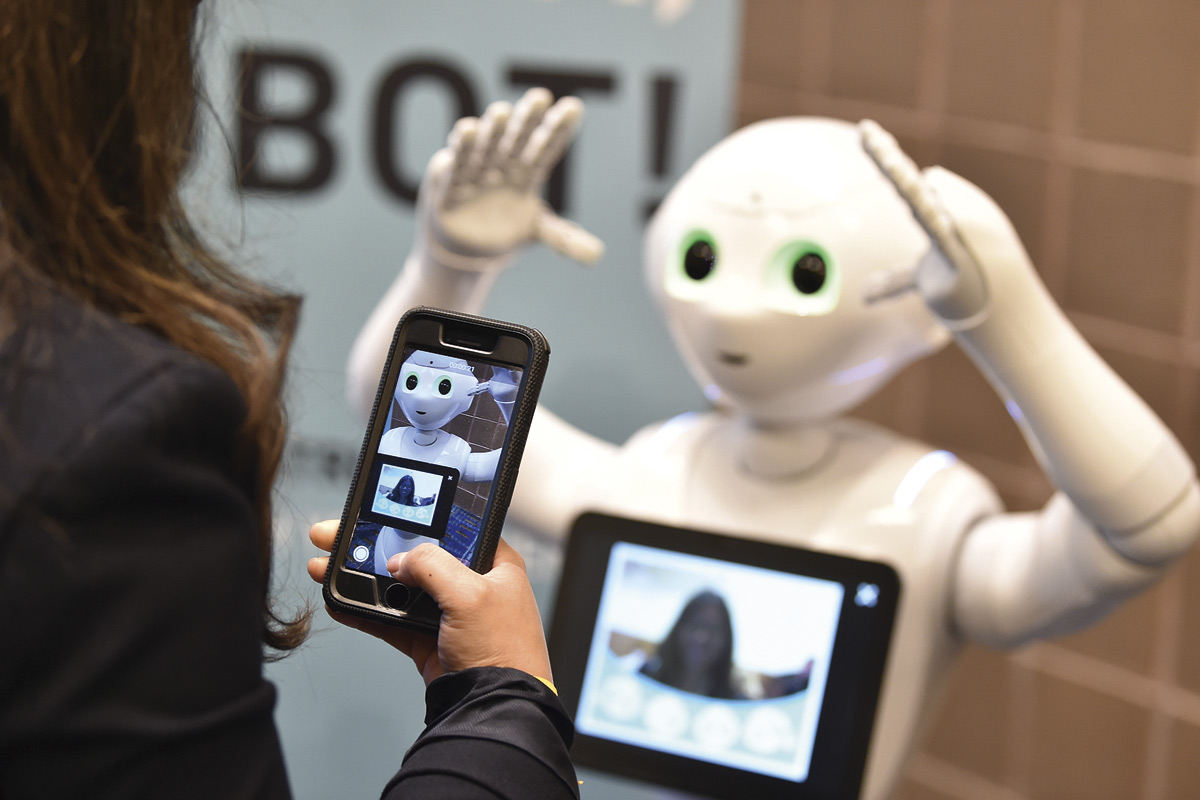

The growing interaction with machines poses several questions about which we have no previous experience, nor can we reliably predict how they will influence the evolution of society.

Enjoy red radishes: we look for some seeds among friends and make room for them in out garden so we can have them almost at any time of the year.

Robotics and automation and artificial intelligence technologies hold immense potential in addressing many of the societal challenges as exemplified in the sustainable development goals of the 2030 agenda of the United Nations.

Some say that a humanoid should have a «full body» including two arms and legs, exactly like a human. This article intends to cover research on humanoid robotics in a broad manner.

Brain-computer interfaces allow the control of devices without the generation of any active motor output but directly from the decoding of the user’s brain signals.

Deep learning is an undeniably hot topic. However, interestingly, the current success and practice of deep learning seems to be uncorrelated with its theoretical, more formal understanding.

The ultimate objective of the field of artificial intelligence (AI), the creation of a machine with a general intelligence like that of humans, is one of the most ambitious scientific goals ever set.