Search

Every historical period has had its epidemic executioner, and it has almost always been the ecological changes between human communities and the environment that have caused changes in pathogenicity and epidemic diseases.

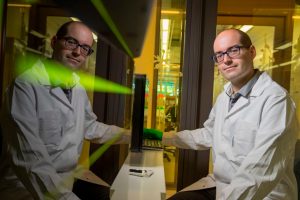

The biochemist Vicent Pelechano, together with his team in Sweden, has developed a simple, fast, and affordable method to detect the SARS-CoV-2 virus in patients. He explains in this interview.

We need to rethink many aspects of our daily lives, of our values, of our economic and cultural practices; in short, of our coexistence with the rest of nature and, especially, of our respect for non-human animals.

Is the planet benefiting from a halt in human movement? Is pollution decreasing? Experts from the Polytechnic University of Valencia and the University of Valencia reflect on the environmental impact of confinement policies.

Most probably, the current coronavirus1 pandemic represents the uncertain epilogue of an epidemiological period marked by the renewed prominence of the infectious disease in the last decades of the twentieth century

Next time we could be facing an even deadlier virus than SARS-CoV-2. Now is the perfect time to start working.

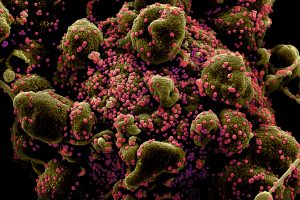

The history of coronaviruses as human pathogens dates back to the mid-1960s, when they were first isolated from respiratory tract samples extracted from adults with symptoms of the common cold. Currently, seven types of coronavirus are known to infect humans.

The current healthcare crisis forces us to reflect on the way to act, the resources available to science, or the importance of good communication.

Knowing the detailed genomes of viruses and their phylogenies allows us to understand the origin of the outbreak. Was it a zoonosis from bats or were other hosts involved? Where did this fatal transition occur? What is the rate of change of the virus?