Today, I would change the title and content of the monograph: «From the enchanted cove to the busted cove», because the dossier published in the summer of 2012 belongs to a different time in which we did not revere tourists any more, but we did not hate of abhor them. Of course, hotels and associates – an important sector for the Balearic Islands – think otherwise, if they do think about it at all. We have lost not only our identitary features, but also privacy: there is no corner of the city of Majorca or the rest of the island free from the presence of a rather striking or uneducated invader. Rustic (territorial) heritage is slipping away; foreign owners cut or privatise roads, close what was ere open field with barbed wire or walls, lock themselves within their ghettos. Urban and rural tradition decays; civility in urban areas dissipates (night rest, for instance), even in the most traditional neighbourhoods; very few people greet each other in the streets of little towns…

«Rustic (territorial) heritage is slipping away; foreign owners cut or privatise roads»

Many years ago (1981) I wrote that massive visits led to the destruction of nature… It is a selfish stance, I must confess, with the implied reasoning «I am the respectful one, the clean one, the ideal citizen to whom enjoyment is due, the beneficial owner of nature; the rest are…» And this concerns especially the coastal strip where nature was particularly lavish. Those areas show – sometimes in the true explosion of biodiversity that are wetlands – the lithosphere (the ground), the atmosphere (the air, wind, rain…), the hydrosphere (the sea and fresh water) and the biosphere (animals, plants, and… humans). The ecotone is sometimes so complex that it would be necessary to treat it with exquisite respect.

The 2012 monograph focused on a restricted concept of cove, the one referring to our limestone coasts, that are prototypical in Menorca’s Migjorn and in Majorca’s Sa Marina, where we can find hundreds of them. The contrast between an estuary and a cove is not forgotten, where the former refers to a river mouth invaded by the rising sea and usually subject to tides; while the cove, sensu stricto, often connects with ravines or ephemeral «Streams», yet does not obey to a system of fractures or to Karst dissolution. These sea invasions are always long, rather than wide, and the limestone substrate is implicit.

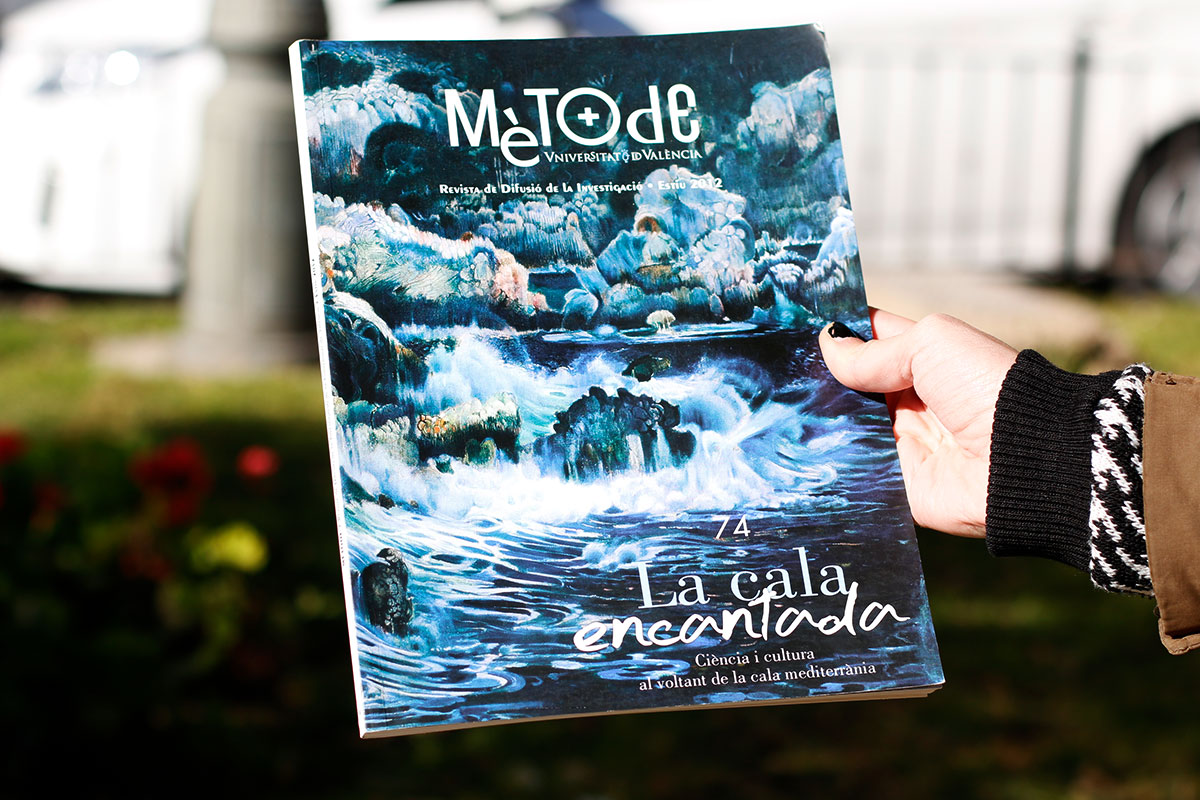

This collection of articles included writings by scientists (geographers and geologists, including submarine spelunkers) and writers (literary critics and art commentators). And a precursor, the traveller archduke Ludwig Salvator of Austria who introduced the Balearic coasts to scientific and travel literature with Die Balearen (1869-1891); Albrecht Penck (1894) might have extracted the concept of cove as Ingressionsbuchte from him. To finish, I would like to make a special mention to the artists and writers. Particularly to Joaquim Mir, the best landscape artist of his time, who arrived together with Santiago Rusiñol and painted the avalanche of light and blue that is The enchanted cove (1902). A few years later (1907), Miquel Costa named Formentor «the corteous cove», the object of his walks. Blai Bonet (Entre el coral i l’espiga, 1952) transfigured the Figuera cove, almost intact at the time. But Calaloscans (1966) by Bartomeu Fiol was the one to change the course of the usual optimistic landscape: we went from the paradise cove to the «unfriendly cove», the curse cove», the «hysterical marine». Predators had arrived.

Despite the declaration as world heritage and as biosphere reserve, concrete and cement keep undermining the landscape: they are «collateral damage», justified by capitalism.