Interview with Cordelia Fine

«Neurosexism justifies old-fashioned gender stereotypes and roles in ways that aren't scientifically justified»

Professor of Psychology at the University of Melbourne (Australia)

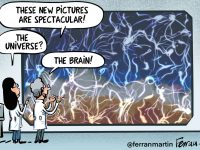

New arguments for old stereotypes. That’s how professor Cordelia Fine describes «neurosexism», a term referring to the use of neuroscience to justify traditional gender role models, models that do not include the stereotype of the female scientist. That might somewhat explain the poor presence of women in high-level research positions (only 20%) in Spain, as recently published by Materia.

Cordelia Fine, professor of Psychology at the University of Melbourne (Australia), published Delusions of Gender in 2011, in which she delved in the issues around neurosexism, a theme she has also researched in different academic papers. The last of them was published in Trends in Cognitive Sciences. In the paper, she proves how easy it is to find newly published books defending sex-difference through neuroscientific aspects, and how the media reproduce the same patterns.

Professor Fine participated in ESOF 2014, the European science conference that took place this year in Copenhagen, and we could talk to her about neurosexism, women and science.

I would like to start with a recurring question when we deal with differences between men and women. What makes us different, biological or social factors?

I think what’s changing in researching gender and biological sex is that for a long time you needed to have two parallel streams of research. The one that’s looking at social influences on gender – psychology and social circumstances and so on – and then a parallel stream that’s been interested in genes and hormones and brains. What we’ve realized for a long time is that these two aren’t really separated. We have no pure biological variables. All of our hormones, and genes and our brains are sort of entangled with the physical material and social experiences that we’ve had. What we’re starting to see in gender research is a bringing together of the two kinds of research, and I think it’s quite an exciting time from that point of view.

Photo: Anna Mateu

In your books you write about neurosexism. What does the term entail?

Neurosexism describes the use of neuroscientific claims or language to justify old-fashioned gender stereotypes and roles in ways that aren’t scientifically justified. So that last part is very important. Some people think that if you criticise neuroscience scientific investigation of sex differences, that you’re just against it across the board, you just think it is intrinsically wrong. That’s not the case, it’s poor methodology, systematic biases, its overinterpretation, that produces results that support a kind of stereotypical view of the sexes in a way that actually doesn’t have reliable science behind it.

But it is true that our male and female brains have different structures, so it seems only logical to think that they work differently and make us different.

That’s the standard story, but there are three main issues with that line of argument: One is often is the case that one particular study can often have small sample sizes, and when being replicated, there are major issues. The second point is that we are not far enough along our journey in neuroscience to know what it means psychologically for a brain structure to be different or for a pattern of brain activity to differ between males and females, so people can make speculations, and often those speculations are formed by gender stereotypes. And the third problem, of course, is that just because you see something in the brain it doesn’t mean that is hard-wired or innate, because our brain is developed through constant interaction with the environment. When you think about how gender as a social phenomenon influences the life that you have, the hobbies that you take up, or the jobs that you do or the educational path that you take… it would just be amazing if we had identical brains. So these are the three key issues. Is the result reliable? What does it mean psychologically? And where did it come from?

But there are differences that we accept as natural, especially when we see children reproducing it at an early age. You comment as much in Delusions of Gender, how some parents feel sure that they offer egalitarian education but they end up accepting innate sex differences observing their children. Do we learn how to be a girl, how to be a boy?

I think to the extent that the meaning of being male or female does change starkly across times, it’s clear that to some extent we develop a gender identity. But at the same time I don’t think that means that we are slaves to cultural norms. We might start off with quite small predispositions that differ by sex, and culture sort of enhances response to those and reinforces them. But should we place so much weight on small differences and biological predispositions? In the last century we thought of development as basically travelling from genes to hormones to brain to environment, and now we have much more interactive, complex models, where everything is supposed to be seen as equal, co-constructing the individual. I think we have to think about how to take those changes to scientific models and relate them to how we think about gender and small differences.

Reading books like The Female Brain by Louanne Brizendine, which you put as an example of neurosexism, I had the impression that the book had a somewhat soothing effect. That is, women are the way we are because of our genes, so we can stop fighting for equality, a fight that demands a lot of effort everyday. What do you think about this?

I think that’s part of the appeal of these books. It is actually more comforting to think that, that it is natural, inevitable, that to some extent we can relax now because we reached the limits of equality, everything is fair now, there’s an equal playing field. There is a common impression that, since there’s legal equal opportunity, people assume that there is also psychological equal opportunity. I don’t know what the limits of equality are but I think it’s certainly not the case that we have equal psychological or social opportunities still, because we have a huge amount of cultural baggage about gender, and we carry it around with us.

This cultural baggage also influences researchers, as you mentioned in Delusions of Gender, and personal prejudice can affect the results or design of an experiment. To which point can we say that science is a product of its social environment?

When I first started to do some research for Delusions of Gender, my target were the popular writers. I was very shocked by what the popular writers were saying, that neuroscience had shown that males and females are ‘hardwired’ differently. Later, when I came to look at the neuro-imaging studies themselves, I was very surprised at the conclusions that were drawn from the studies. There was this dawning realization that science isn’t completely objective, and scientists are embedded in the same culture as the rest of us and that can influence the way they design their research and the way they interpret their research. And that was a horrible shock to me, to be honest, and it became a much more complicated book as a result, because I wasn’t just saying talking about what the science is, but actually the problems in the science itself.

Maybe that’s the reason why you make a difference between good and neglected science. In fact, in your book you claim that those who are interested in gender equality do not fear good science. The only thing that worries them is neglected science, misinterpreted science and neurosexism.

When you look at the evidence for this idea that new-born boys are more interested in looking at moving objects, whereas new-born girls are interested in looking at faces, the study itself is not terribly rigorous, it hasn’t been replicated, all the findings have been contradictory. So I think we need to be careful before saying something like «this is just biological». We have to wonder what’s the rigour of the science behind these claims. And secondly, we have to be very careful about what those particular differences can explain in the world. Boys may be on average more active as infants. Does that explain why they’re more likely to become scientists? Probably not. We have to also appreciate what cultural creatures we are, and make sure that we are paying enough attention to how changing social norms can influence how much girls participate in sport, for example. You can see these enormous shifts over time, and from this be a bit open-minded about what is possible.

Photo: Anna Mateu

What do you think of the way the media communicate scientific results. I feel that we journalists tend to publish more works highlighting the differences between men and women. What is our responsibility?

Clearly, science journalists have the responsibility to report as accurately as they can, but I think the interesting question is at the intersection between science and science journalism. You can’t all be specialists in the particular fields that you’re reporting on. And of course, if a scientist is being more speculative and presenting more exciting stories, he’s more likely to get picked up by the media. So I think it’s not fair to just scapegoat the journalist.

Preparing this interview, I reviewed the representation of women scientists in the media, and their presence is almost anecdotal. How does this influence the social perception of women scientists?

I do think it is important that women get the representation that they deserve, and not be underrepresented. But that, again, can’t just be the responsibility of the media. There are many impacts on the younger generation, who is thinking about being a scientist. There’s been some wonderful work showing that children studying science learn about male scientists. When children want to make sense of that, they might think that women are just not cut out to be scientists. If we explain to them that women were not actually allowed to go to universities and do this sort of thing, they would discover it is not because females are not good at science, it’s because they’ve had these obstacles; and that actually increases their interest. It’s obviously an important issue.