Search

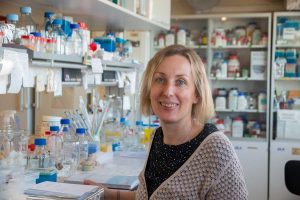

I am Glòria Sánchez, researcher at the Institute of Agrochemistry and Food Technologies (CSIC) in Valencia and principal investigator of the Environmental Virology and Food Safety Group. Our group works with food-borne pathogens and we have three lines of research. On the one hand, we

Cristina Crava, Ramón y Cajal researcher at the BIOTECMED group, develops techniques to improve the use of entomopathogens to control crop pests.

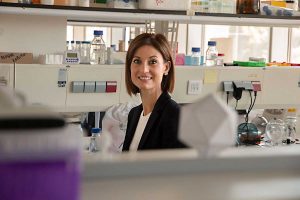

Pilar Domingo Calap combines her Ramón y Cajal research work at I2SysBio, where she leads the «Environmental and Biomedical Virology» group, with teaching at the University of Valencia in the Department of Genetics.

The covid-19 pandemic has altered the infection routines of other respiratory diseases and, in some cases, has made us more vulnerable. The ancestral method of immunisation in pre-vaccination times was, precisely, infection.

The outbreak of H5N1 avian influenza declared in October 2022 in an American mink farm in Galicia is concerning because of the level of transmission from animal to animal.

Although a One Health perspective has, in one way or another, been around at least since the time of Hippocrates, the term itself was coined by William Karesh in a 2003 The Washington Post article. Since that time, the concept has been discussed, applied, and

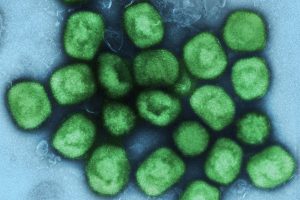

Monkeypox circulated under the radar for an undetermined period of time in many non-endemic countries. How did this happen?

The use of phages in biomedicine can address the problem of multi-resistant bacteria. However, there are some weak points we must overcome before using them in clinical practice.

The scientific community agrees that viruses are not alive. However, the idea sparks some debate because it depends on how we define life.