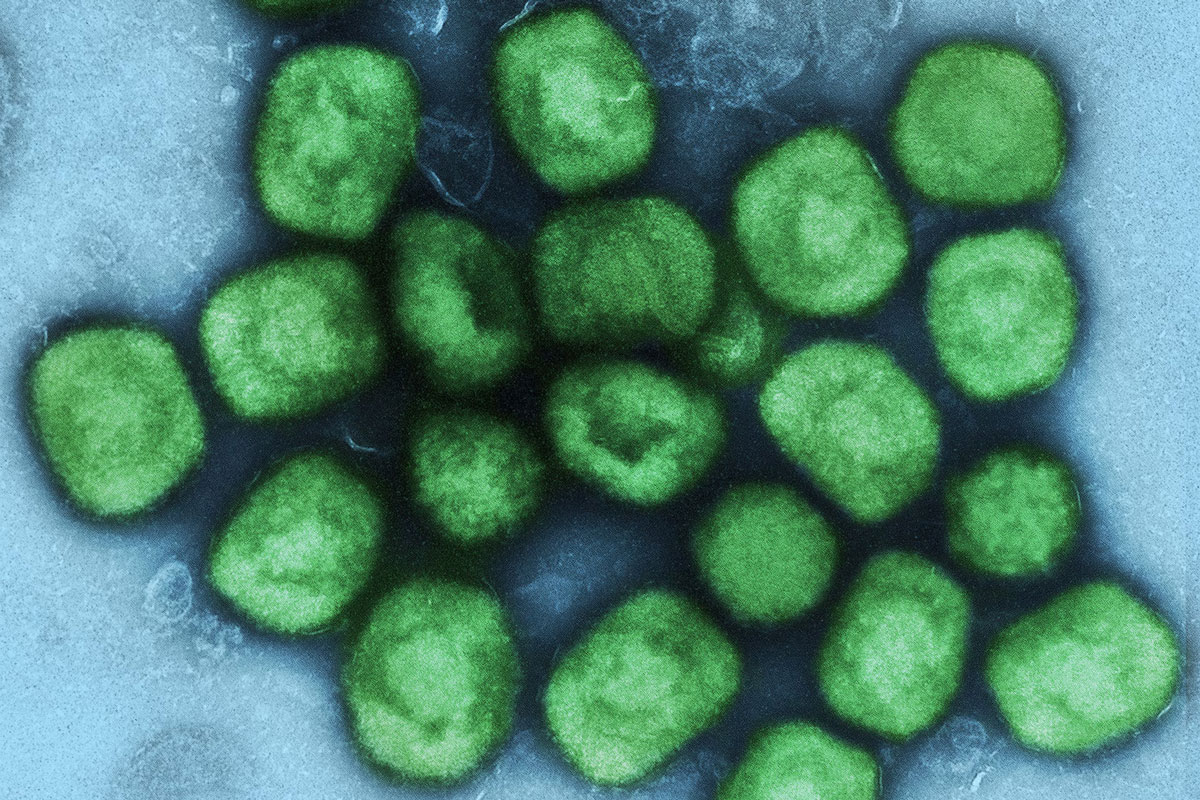

The steady trickle of monkeypox cases in different corners of the world is keeping health authorities on tenterhooks. The World Health Organisation (WHO) said at a press conference on 14 June that «the global outbreak of monkeypox is clearly unusual and concerning». Their director, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, has convened the Emergency Committee for 23 June to consider whether the outbreak represents a public health emergency of international concern, and says they do not want to wait «until the situation is out of control».

So far, more than 1,600 cases have been confirmed and almost 1,500 suspected cases have been detected in 39 countries. In seven of those countries, the virus was already endemic, while in the remaining 32, the pathogen was identified for the first time. A total of 72 deaths have been reported since the beginning of 2022, all of them in countries where the virus had been circulating for years. In Spain, 313 cases have been confirmed, most of them in the Region of Madrid (194). 308 of the cases are men and, according to the available data, transmission has occurred through intimate and prolonged contact during sexual intercourse.

The WHO suggests that the transmission of monkeypox may have gone unnoticed for several weeks or even longer before the health alarm was raised. The sudden and unexpected appearance of multiple cases in different regions of the world, unrelated to travel to areas where monkeypox is endemic, points to this phenomenon.

How could monkeypox spread off the health care radar?

There are several reasons why this emerging disease has slipped off the radar and spread outside the African continent without raising any alarms. First of all, the disease was mainly confined to seven countries in Africa, where it remains endemic. Healthcare professionals in the countries where cases are being detected for the first time had probably never encountered the disease before and therefore lacked the expertise to diagnose it.

Faced with a series of symptoms and signs of a disease, doctors will then consider the most likely causes for diagnosis. Hence the famous aphorism, widely used in medicine: «when you hear hoofbeats, think horses not zebras». In other words, when faced with a series of signs, it is advisable to think of the most frequent causes and not of the unusual. An idea that brings us back to Occam’s razor: «all other things being equal, the simplest explanation is usually the most likely».

Unfortunately, this is a problem when we are dealing with a rare disease or a disease that is totally unexpected in a country (such as monkeypox). To diagnose a disease, you need to consider it, and hardly anyone thought of monkeypox until the outbreak was announced. It was a zebra in the middle of the European continent. It was an exotic thing, and you had to be able to think about it in order to diagnose it. Doctors thought of horses such as sexually transmitted infections.

On the other hand, the fact that Spain is the only European country without a speciality or sub-speciality in infectious diseases could have contributed to the fact that many cases were detected a posteriori, after the announcement of the monkeypox outbreak in the media. Without formal and specific training in this field, such cases are more likely to go undetected.

During the recent conference of the Spanish Society of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology (SEIMC), the Director of Infectious Diseases of the Gómez Ulla Military Hospital, Francisco Javier Membrillo de Novales, pointed to this reason and explained, regarding a clinical case of monkeypox: «The truth is that now we all see it and it is a textbook case, you can even see its adenopathy, but this has passed in front of many doctors in Spain during the previous weeks. There is no doubt about it. Patients were telling us and we did not suspect it. And now we see a series of cases because many countries have gone through the same process as Spain. We detected the cases the day after they appeared in the media».

Another reason monkeypox went unnoticed is its variable clinical manifestation. The WHO reports that «many cases in this outbreak are not presenting as the typical clinical picture of monkeypox», which features fever, swollen lymph nodes, and characteristic rashes on the face and extremities. Some of the atypical features being documented include: few lesions or only one skin lesion appearing in the genital or perineal/perianal area and not extending beyond… On the other hand, the localisation of these lesions, and their generally favourable resolution with no complications in developed countries, may also have deterred some patients from seeking medical attention.

Monkeypox is not the first, nor will it be the last, emerging infectious disease to circulate undetected in Spain for an undetermined period of time. Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever was already present in Spain since 2013 and a timely coincidence led to its identification eight years later. Humanity faces an ever-increasing risk of emerging diseases, and if epidemics such as monkeypox, COVID-19, and the Crimean-Congo fever teach us anything, it is that being prepared for the unexpected might be one of the best investments we can make in the future.