Interview with Angela Saini

«We should study race as a social phenomenon, not as a biological one»

Writer and science journalist (UK)

In 1907, a large colonial exhibition was held in Paris at Garden of Tropical Agriculture within the Bois de Vincennes. There, five different villages were recreated and, in addition to typical constructions and landscapes, people belonging to the each represented culture were part of the exhibition. Nearly two million visitors went through that human zoo in six months, some observing in awe what they considered to be just another exoticism; others taking notes that would lay the foundations of race science.

In her book Superior, the scientific journalist Angela Saini (London, 1980) described her visit to the site (a sort of «Edwardian Disneyland», in her words), a park which remains open to the public but without much indication of the event, with ruined monuments and no sign explaining why they are there. A good metaphor for what happened with the colonial past of so many nations: it became a shameful relic a shameful relic best left unmentioned.

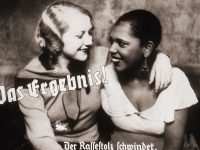

This is not the first time that Angela Saini has taken on the confusions and prejudice affecting scientific research. In her previous work, Inferior, Saini focused on how science has studied the differences between women and men, while in Superior she brings us to the origins of scientific racism to show its ramifications. The science of human difference was born in the years of colonialism and slavery; it divided the world into races and placed the white race on a biological step higher than the rest to justify the conquest of territories, the plundering and annihilation of wealth and populations. Inevitably, these facts have left a mark in scientific research to this day and Saini confronts this fact without hesitation.

Superior, published in English in 2019, was considered «Book of the Year» by the Financial Times, The Guardian, and The Telegraph, as well as being included among Nature‘s ten best 2019 books. As the author tells us, this book caused strong reactions between white supremacist groups, but also many scientists and institutions wanted to work with her towards a science that studies human beings detached from race science. In fact, Prospect magazine included Angela Saini in the list of the 50 most important thinkers of 2020. Superior has been recently published in Spain (Círculo de Tiza, 2021) and we have had the chance to talk to her about it at length.

Your book shows how keeping the concept of biological race in science research never actually works. It never provides reliable enough data. Why do many researchers still use it in their research?

I think it has to do with the way we started to think about human difference right from the beginning, from the Enlightenment onwards, at the birth of modern Western science. There were certain assumptions about the human species, some to do with gender –for example, that women were not the intellectual equals of men–, and some to do race and ethnicity. Even the idea that we can be divided into discrete groups is a political ideal, because it does not exist in biology. There are no hard discrete different human groups in biology, we are very homogeneous as a species. In fact, we are one of the most homogeneous species on the planet. Also, the way we are divided is always going to depend on the politics or the social world that we are in. So, when this Western European scientists came up with the categories they did, they were informed by the world around them. They were informed by colonialism, notions about European superiority, about slavery… All the different hierarchies that worked in the social world were imported into the science of human difference and that became the basis for research. So, for hundreds of years that is what scientists used to do their research. Racial assumptions, as well as gender assumptions, were baked into scientific research from the start, and it is very difficult to let go of these ideas once they are deep-rooted within you, within the establishment.

Besides deep-rooted ideas and prejudice, do you think there is deal of scientism involved in this matter?

I do, and in fact a lot of my work over the last years has focused on the problem of scientism. There is a degree of arrogance and hubris in an establishment which believes itself to be perfectly objective, that we sit above society, that we are not affected by politics, that this is not a problem for us because we deal with data, we deal with empiricism, and that is beyond any of the everyday problems of people. That has never been true. Scientists are human beings like the rest of us, they sit within society, they are affected by society, the questions they ask are always affected by society and if they fail to recognise that, they fall into the same traps that scientists in the 19th century fell into, which is looking at the world around them and assuming that the inequality, for instance, is biological. Of course, it is not biological, it is a product of very different factors and we have to appreciate all of them.

«I would love a science of difference that looks at us as individuals, that understands that every single person is unique, and we are a confluence of different factors»

Instead of trying to discover genetic differences between people who basically look different, what other questions could science be asking to understand, for instance, health differences between people?

I would love a science of difference that looks at us as individuals, that understands that every single person is unique, and we are a confluence of different factors. Not just genetics, but also the way that we live, where we live, the diet that we have… Most of the things that kill us, that kill human beings, in the West at least, are things like heart diseases, strokes… Things that are very heavily mediated by the way we live. So, I would love to see a science of human difference that takes into account all those social determinants of health as well as looking within our bodies. We have to remember that individual difference is where the vast majority of human difference sits, most of it does not sit at the group level. There are very few diseases that show population level differences, and even then, it is statistical: it is not the case that there is a gene that exists in all the members of one population and not another population. There are no «black» genes, nor «white» or «brown» genes. We have to understand all that if we want to have a truly tailored personalised health care system.

In the book, we can find two main expressions of race science: racist scientists exploiting scientific structures like the publishing world to justify their believes, but also people who consider themselves to be antiracist who still think the concept of biological race is worth exploring. Do you think the latter perspective somehow helps the former to remain, even if residually, in the scientific sphere?

Yes. I think that confusion is what makes it possible for these ideas to remain alive within the sciences. Mainstream science keeps these ideas alive because there is enough of that narrative, enough of a belief in race to keep that within the equation when it should have left the equation a long time ago. Or, at least, if it stays in the equation, it should stary as a social quantity. For example, a hundred years ago it was quite common in Britain for scientists to think about different classes being genetically different, that very poor people were somehow genetically weaker than wealthier people. And, generally, we do not think those terms anymore. That is how we need to think about race. We need to think of it as a social quantity in the same way that we think about class as a social quantity, so that is not to say that we should not study it, but we should study it as a social phenomenon, not as a biological one. And I think sometimes that fine line gets confused because even as a social phenomenon, it can have an impact on health. For example, black Americans die of almost everything at greater rates than white Americans, but it does not have to do anything with «blackness». The reason that we see these differences is because people are treated so differently, they live different lives based on the social perception of who they are, in the same way the poor live very different lives based on the circumstances and the perception of who they are. But it is very easy for that to bleed into this idea that there are genetic differences as well.

How can race science, even if supposedly marginal and located in only certain groups, end up reinforcing stereotypes in society?

There are two ways of approaching human difference: one it is just saying that we are pretty much the same underneath, and that there are also marginal statistical differences that make us individually different, and then some very small statistical differences that you may see between population groups. The other is to focus on all the marginal differences at the edges. The narrative that you chose really guides the way the public thinks about human difference as well, and I worry that scientist have been so focused on the differences they have not emphasised enough the similarities between us, the fact that we are pretty much the same underneath. For example, since the vaccine for COVID-19 came out, there has been some slow uptake of the vaccine about ethnic minority groups in the UK, and I have had people say to me: «Is it safe for me to take the vaccine? I am brown, or I am black, and I do not think it has been tested on black people». And after all it does not matter who is being tested on, as long as you have a wide enough sample. We are not that different underneath that a drug tested on white people will not work on black people. But I think because the narrative around race and health has been so focused on the little differences, it gives the impression on the public imagination that those differences are salient when in fact they matter hardly at all. So, I think scientists have to accept some culpability for that, the media has to accept some culpability as well, because it is about narratives, it is about storytelling, about the way that we tell the story of human difference. And I do not blame the public that sometimes fall under these misapprehensions when they are told these stories.

In one of the last chapters, you actually explain how in the US a hypertension drug got approved as a medical treatment to be solely marketed to black people…

Yes, this has to do with long-standing racial myths around hypertension [as a disease that particularly affects black people]. These ideas have been around for a long time, particularly in the US, but also in the UK to some extent. There are more black patients present with higher hypertension, but we have to remember that hypertension is heavily affected with how you live, diet in particular. For instance, my mum has hypertension and I know that is because her lifestyle and what she eats. It is affected also by being an immigrant: there are studies that show that your blood pressure is higher if you are an immigrant because of the pressures and the stresses of living that kind of life. Therefore, to assume that there is some genetic difference again I think speaks to the desire in the medical community to have a very simple biological explanation to what is a very complex social phenomenon.

«We are not that different underneath that a drug tested on white people will not work on black people»

Even in supposedly well-meaning projects, you remark in several parts of the book how the methodology to study biological differences between populations has often been problematic, especially regarding data and privacy protection.

That has certainly been an issue historically. We have seen for instance that there has been abuses of data, especially when it comes to indigenous populations. In the last twenty-thirty years, there was a big push within population genetics to study isolated indigenous groups because they imagined they might be genetically different in some ways. It has turned out that they are not that genetically different. But in the process of doing that, sometimes they used data in ways they were not intended to. There has been a lot of activism around this as a result, people have been concerned: when they hand over their DNA, will it be used to benefit them, or will it be used to try and prove some kind of genetic difference or genetic inferiority, or to claim that they are distinct or strange in some other way? Those mistakes have been made, and sometimes by very-well intentioned people… I think they have done enormous damage to science, but I still see that happening now. I still see scientific researchers tell minority groups «if you do not participate in our clinical trials, our drugs might not work on you» which is threatening and false. That is no way to approach this kind of research. What we need to continually remind people is that it is good to have diversity in clinical trials, but not because we are different as groups, but because we are different as individuals and a broad set of people will always be more reliable than a narrow set of people. Look at the COVID-19 pandemic, the biggest differences we are seeing are between age groups, and how many clinical trials use age as a variable, or run tests on older people? Very few, most clinical trials are done on younger people and yet, we do not consider that as salient factor. So, I wonder sometimes about why we pick the variables that we do. Not every variable will always be salient depending on the context. If we pick certain things over others, we have to explain why we are choosing those things and involve people in those discussions, rather than assuming that we are going to see the differences that we think that we are going to see.

Due to its recent history, would you say that the US are as the core of race science today?

This is tough one because I do think there are a lot of racial myths in American society because of its history, and those myths probably survive in wider society and scientific communities because of it. But I have to say here that also in the US there is a very mature and intelligent discussion around race and health around the social determinants of health. Some of the best research within the social sciences around race is in America. In that sense, in the UK we are lagging a bit behind, that we still think sometimes in genetic terms first and social terms second, whereas in the US I think that narrative is already shifted. I do a lot of talks to American universities and I have done a couple of talks in the National Institutes of Health last year… And I am really heartened to see how much they already moved on when it comes to this debate.

You also mention how other countries such as China or Russia, or India even, are now trying to prove that their ancestry goes back before Homo sapiens even left Africa… Why do you think these countries are insisting in these myths now, as well?

I do not think it is countries as a whole, I think it is certain political forces within these countries and it speaks to the rise of ethnic nationalism, religious nationalism… For me, this has disturbing echoes of what happened in Nazi Germany, where the party also tried to create this myth of a Germanic race biologically different from the other ones, and then tie that with this «blood and soil» idea. According to that, if they could see evidence of this Germanic race anywhere in Europe, then they could claim that territory. That also obviously also became the underpinning for the eugenic programme of racial hygiene that led to the Holocaust. And I see those same undertones in modern-day ethnic nationalism trying to tie some idea of genetic difference to their claims to land, or claims to territory, or to origin myths. Every nation, every community in the world has its own origin myths. We should understand them as stories, they are stories, fairy-tales in a way, that serve a political purpose and sometimes very valuable in our kind of human conception of who we are and what our values are, and how we think about ourselves. The problem is when we start to imagine those origin myths are biological rather than ethical or legendary, and I think that is what we are seeing happening in countries like Russia, India, and China, when we see scientists or politicians trying to appeal to biology to support their ideologies.

«Scientist have been so focused on the differences they have not emphasised enough the similarities between us»

Do you think there is way to prevent active racism to exploit the scientific structures or methods?

We have to understand that science is not something that exists separately from society, it is within society. It has to sit within the real world, it has to interact with it, and it has to do that in an honest and truthful way that acknowledges its fallibilities. And I think we need to engage with the public in a way that acknowledges that scientists do not know everything all the time, and that they make mistakes sometimes, and they disagree very often. If the public see how it works in practice and not assume that scientist know everything because [laughs] they are smart and work in these universities and they have all the information… If we could acknowledge that, then I think trust in science with go up, because then we would see it for what it is, rather than imaging it to be something perfect. It is impossible for it to be perfect.

Your previous book was Inferior, which was about how science has studied the biological differences between men and women, again often leaving out social aspects to explain these differences. I wonder if you have found similarities between race science and how science has historically studied women?

This is a tough one because sex is not completely a social construct, we know there are some kind of hard differences between men and women. But I worry that people are falling into the same traps regarding race differences when it comes to sex differences. For example, I have heard some activists claim that drugs tested in men will not work in women. We have to be careful there. It is not necessary the case that drugs tested in men will not work in women. For example, I am allergic to penicillin, my dad is too, and it has nothing to do with my sex, it is just because we are all individually different. Most drugs do not work in everyone, because of that individual difference. But I also have hormonal migraines, and it is heavily to do with my sex, because my hormone levels change during my cycle. So, in one case sex is salient and in the other it probably is not. So, we have to be careful so that we do not assume that men and women’s bodies are completely different in every respect and that, within those groups, that men are completely the same as each other and women are completely the same as each other. While sex may be important when it comes to certain things, that does not mean it is going to be important in everything. In a social media age, it is very difficult to get across this message that we do not have to be completely different or completely the same. It is possible for there to be some areas in which differences do matter, and many areas in which differences do not matter, and for both of those things to be true without having to fall into one specific narrative. We much about women’s health, we know that because of sexism sometimes in medicine women are let down. But that is not because of their bodies, but because of sexism in medicine. We have to understand the nuance and focus on the variables that matter depending on the condition that we are looking at. With COVID-19 is not sex, it is age, for instance. For hormonal migraines, it is sex. It really depends on the question that you are looking at, and I worry that we are just taking blanket approaches, let’s test race, let’s test sex, and see what the differences are. It is very crude, and it does not do justice to human variation.

In fact, to go back to what you are saying before, for COVID-19, sex might be a factor, but then again a more social one. In Mètode we recently published an article about how in Spain, although the mortality rates were higher in men, more women caught the virus because they were more exposed as front-line health workers and carers…

In the UK too we saw men quite heavily affected at the beginning, when the virus hit London, and that was partly because a lot of delivery drivers and taxi drivers tend to be men. It is a social demographic thing, and so of course the data is going to be skewed. We have to be very careful not to biologize things, especially in a pandemic: a virus does not enter into a country and spreads evenly across and affects everyone in the same way. It really depends on demographics and occupation and if you are a front-line worker or not, if you work in a hospital… Like I said, we want simple explanations for why we see the patterns that we do, and there are very rarely simple explanations.

What reactions did you get to this book from people who pursue race science actively? I am thinking of people you interviewed for the book, for instance…

It has been nearly two years since Superior came out and I have had white supremacist organisations after me, after my family, my seven-year-old son…. They were writing articles about him, about my husband, my parents, my sisters… The abuse got so bad I left Twitter and other social media… It became impossible, I could not block fast enough so I had to leave. It was pretty awful.

That is absolutely terrible. I confess I was thinking more of an academic reaction, I had no idea that it had gotten so bad…

Well, in the academy reaction at first there was a little bit of pushback from population geneticists, you may remember that there are a couple of chapters where I criticize some of the racist undertones of population genetics. But now I work with some of those people, and we have forged a really good relationship. I see already the narrative within population genetics community is changing because there is an acknowledgement that mistakes have been made in the past, and that we do need to think more carefully about the way that we structure these debates. But I have to say, the biggest difference came after the George Floyd murder. When the Black Lives Matter movement happened last summer, the scientific community completely changed the way that it talked about these things. Suddenly, all the things that I had been writing about, which had sometimes had pushed back too, especially from doctors… Suddenly, doctors wanted to accept what I was saying and were asking me to work with them, so now I work with a lot of different groups, and I sit on the board of a number of scientific institutions and museums, and I am trying to work behind the scenes with universities to try and develop curricula that helps us understand these questions better.

That is proof that the book was necessary…

I do not know about that, there have been other similar books throughout the decades, but I think it came along at the right time maybe, and the message hit at the right time, which is lucky.