Women… courageous and wise

European women in Africa

Until relatively recently, women have had problems gaining access to jobs traditionally taken by men such as medicine, professorships and research. Some women, however, like the three given as examples in this article, managed to become pioneers in the most difficult disciplines and areas requiring utmost dedication.

Keywords: anthropology, ethnography, research, travel, women.

So what about women? Were there any lady-scientist travellers? We know full well there were women accompanying army campaigns or crusades and colonial conquests, and particularly participating in the great pilgrimages (like Santiago) along the dusty roads of medieval Europe. But it is also true that to find women who persevered to discover and convey new knowledge and who achieved appreciable scientific results that have left their mark, we cannot go too far back in time. Indeed, such women are practically limited to the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, when women started to gain access to higher education and began to be accepted into academia, which had previously been reserved exclusively for men (Godayol, 2011).

Social transformation and the birth of the independent woman

For centuries, cultural stereotypes became consolidated, differentiating jobs and tasks as gender-specific, but after the industrial revolution things started to change. One thing to remember here is women’s gradual access to formal education, which was initially reserved for men. Thus, women could begin to enter exclusively male professions such as medicine, teaching and research.

To reconstruct the origins and consolidation of industrial capitalism from the eighteenth century and early nineteenth century falls outside the scope of this article, nor shall we discuss how a new social culture emerged among business elites and professionals, which promoted activities such as collecting, travelling and sponsorship. With this came a new conception of the role of women within the family, and the social impact that would arise from the access to higher education of young women in these social classes. These changes encouraged some of these young women to join the world of science, and in some cases their taste for adventure led them to become heroines at the forefront of research in the most difficult disciplines and areas requiring utmost dedication (Morato, 2005).

«In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, women started to gain access to higher education and to be accepted in spheres previously dominated exclusively by men»

To illustrate this, we will discuss three women explorers, daughters of a doctor, a lawyer and a recognized artist. All three travelled around different regions of Africa, always up against harsh and often dreadful conditions. They all took an interest in the African peoples: as the ancestors of modern humans, as recognized victims of slavery, or as fighters against colonialism. All three women had a passion for life and adventure, and were unique in their day: Mary Henrietta Kingsley and Germaine Tillion, both ethnographers, and Mary Leakey, a palaeontologist. These three researchers represent just a small sample of the many women who worked and excelled in all fields of science and on all continents.

Mary Kingsley, African Queen

Mary Henrietta Kingsley (born London, 1862; died Simon’s Town, South Africa, 1900) could have been a typical middle-class Victorian woman (indeed, in many ways she was) managing the family home and taking care of her sick mother. Her father, George Kingsley, was a physician with a passion for nature and travelling and had married Mary’s mother (a servant whom he had made pregnant) just a few days before Mary was born. As for education, young Mary was virtually self-taught. Her father’s house was full of books and her curiosity and interest made up for the absence of a more formal education; in fact she learned German to help her father prepare some books he was writing on Africa. During her parents lifetime she remained withdrawn from society.

Mary Kingsley could have been a typical middle-class Victorian woman (indeed, in many ways she was) managing the family home and taking care of her sick mother. While her parents lived, she was a recluse from society. / Mètode

Her father and mother both died in 1892, one shortly after the other and it was then that Mary -freed from family obligations- started her thirty-year-long career, travelling in Africa and studying the African peoples. The very same year her parents died, she undertook her first journey to the Canary Islands. This was her first taste of travel, but it was enough to convince her she could not live without travelling, and she made up her mind to know as much of Africa as she could. So, after doing a nursing course in Germany in the summer of 1893, she embarked in Liverpool to Luanda, capital of the then Portuguese colony of Angola.

From this point began a long journey that led to Cabinda, where she began her research into the native peoples and their religions, on the way she also collected specimens of insects, fish, reptiles and batrachians. She travelled through part of the so-called Congo Free State, then personal property of King Leopold I of Belgium, and was shocked by the cruelty of the colonial system instated there. Then she continued northward, through what was then the French Congo, to Libreville, from whence she sailed to Calabar, capital of the then British colony of Nigeria and on to England.

Mary deposited the collections she had made in the British Museum and delivered her father’s book to the publisher MacMillan, which she had completed with her own travel notes. But she could not wait to return to Africa. Both the publisher and the director of the Department of Zoology of the British Museum, Albert Gunther, provided funds for her next venture. Once again in Calabar, she made her way to the Niger delta, visited the island of Fernando Poo, then a Spanish colony, and finally travelled by steam boat and canoe along the river Ogooué and after travelling overland made her way back to the coast by way of the river Rembué to the estuary in Gabon. She even took the opportunity to be the first woman to reach the Cameroon summit, the highest peak in West Africa.

«Mary Kingsley’s publications are packed with irony and humour, but hold accurate ethnographic analysis, flying in the face of the prevailing views of her time»

In 1899 she undertook her last trip to Africa. This time her destination was the banks of the Orange River in South Africa, but on arrival she found herself in the midst of the Boer War and decided to offer her assistance as a nurse. She was destined to taking care of enemy prisoners at the British naval base of Simon’s Town, but she fell ill with typhus and died on June 3, 1900.

Her publications (Travels in West Africa, 1897, and West African Studies, 1899) are packed with irony and humour, but hold accurate ethnographic analysis, flying in the face of the prevailing views of her time. She bravely voiced her own opinions about the abuse and humiliation of native Africans by the colonials and openly criticised the missionaries, Catholics and Protestants alike (Kingsley, 2001a; 2001b).

Germaine Tillion, nomadic ethnologist

Germaine Tillion (Allegre, Haute-Loire, 1907 – Paris 2008) was the daughter of a magistrate and writer (author of travel guides for various European countries), who died when she was 18. Her mother, also a writer, collaborated with her husband on the Blue travel-guide series (Guide Bleues) for European countries and continued this work after his death to support the family.

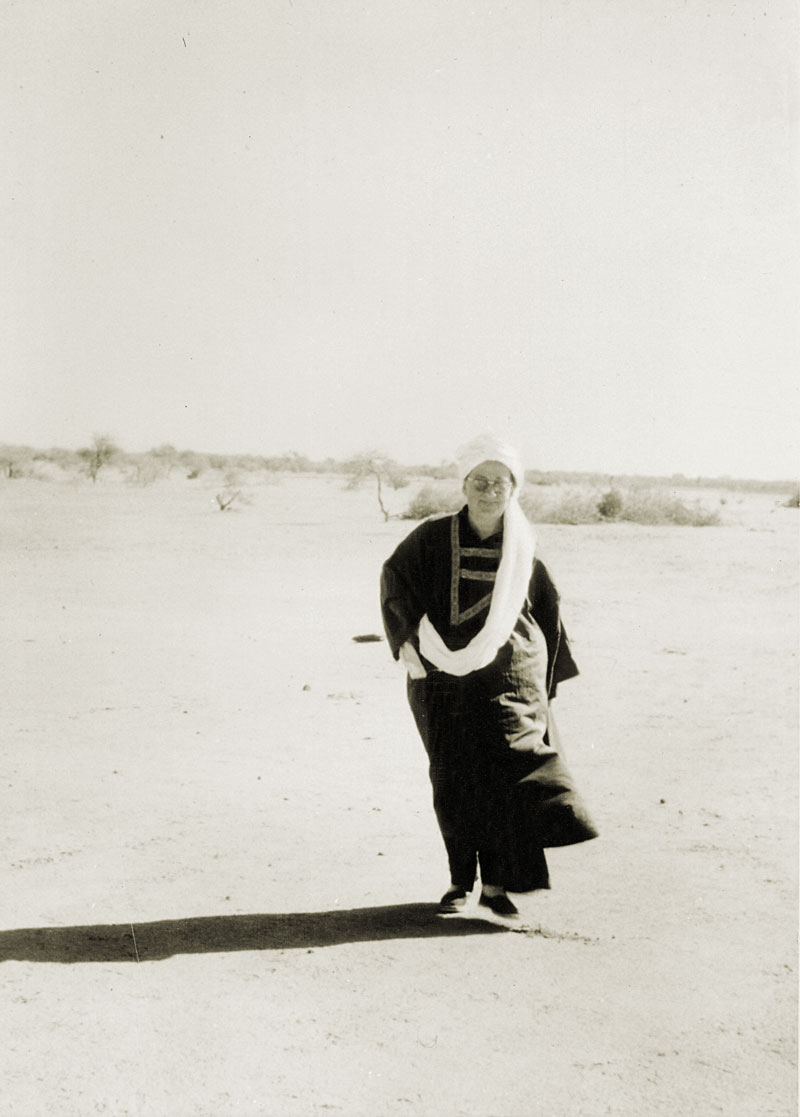

Germaine Tillion spent three years in the Aures mountain range in eastern Algeria, a region inhabited by the Amazigh peoples. Here she lived almost alone, studying the Berber and Chaoui cultures, sharing their nomadic journeys. / Association Germaine Tillion

Despite family troubles, Germaine continued her studies in prehistoric and ancient art at the École du Louvre; folklore, prehistoric and primitive religions at the École Pratique des Hautes Études; sociology at the Faculty of Arts at the Sorbonne; the Amazigh language at the École des Langues Orientales; and, ethnology at the College de France (with Marcel Mauss). After visits to Germany, Denmark and Czechoslovakia, Marcel Mauss managed to get her a scholarship to carry out an archaeological campaign in the mountainous region of the Aures, eastern Algeria, in a region inhabited by the Amazigh. Here she lived virtually alone for three years (between 1935 and 1937) studying the Berber and Chaoui cultures, sharing their nomadic journeys.

On returning to Paris in 1939, she obtained the École Pratique des Hautes Études diploma for her study on the southern Aures nomads, Morphologie d’une république berbère: Ah- Rahman Abdera and then returned to Algeria to continue her research. Back in Nazi-occupied Paris in 1940, she joined the Musée de l’Homme network, participating with her mother in a core resistance organization. Two years later, betrayed by a double agent, she and her mother were arrested (among others) and deported to Ravensbruck concentration camp, where her mother was gassed. Germaine, however, managed to survive possibly helped by the habits she had acquired living alone in difficult places. She even wrote an operetta entitled Le verfügbar aux Enfers (Verfügbar is German for “disposable”, referring to the lowest class of prisoner who is “Ready for Hell”).

After years of activism against concentration camps, based on her experiences, in 1954 she returned to Algeria, which was in a very turbulent state at that time, fighting against French colonialism. Until the end of the Algerian war of independence she was committed to defending the underdog, and trying to end the spiral of executions, torture and terrorist attacks.

This did not prevent her from continuing her research on family structure, which culminated in 1966 with her most famous work: Le harem et les cousins. Her study was to serve as a model for analyzing traditional families throughout the Mediterranean. Its main thesis is that Mediterranean families, regardless of religion, are inbred and seek matrimonial alliances between «cousins».

Germaine lived to a hundred. Her work was a balance between a very strict attitude towards scientific and ethnological description, and an ethical attitude towards the most needy (Tillion, 1966; 2009).

Mary Leakey in Olduvai

Mary Leakey (London, 1913 – Nairobi, 1996) was the daughter of Irish-Scottish artist Erskine E. Nicol, one of the few painters of his time to reflect the horrors of starvation, eviction and emigration in nineteenth-century Ireland. Mary did not study formally, but acquired remarkable skills in drawing under her father’s instruction. From early childhood, she used to go to France and Italy with her family. At twelve years of age, she visited Les Eyzies-de-Tayac-Sireuil in southern France, which holds the Cross Manhon where fossils of the so-called Cro-Magnon were found. This sparked her interest in archaeology.

At Laetoli, the Ngorongoro Conservation Area, Mary Leakey found and described the famous hominid footprints, revealing that they walked upright 3.75 million years ago. / The Leakey Foundation

When her father died in 1926, her mother sent her to a religious school run by nuns. But she was expelled twice. Unable to gain a place at university, she began to attend classes and lectures in archaeology at University College London and the London Museum. Here, her keen interest and skilled drawing brought her into contact with archaeologists, including Louis Leakey, who asked her to illustrate his work Adam’s Ancestors in 1934. This was the beginning of a life-long relationship, which stirred up scandal from the start (Louis Leakey was married and twenty years Mary’s senior – it took over two years for him to gain a divorce). Mary travelled to East Africa with the man she loved, and the Rift Valley was to set the scene of their future discoveries.

Early in her African career, Mary became especially interested in learning about the artistic and manual skills of early hominids. She would soon excel in her ability to guess where to look for -and find- remains, perhaps as a result of her landscape drawing experiences in the Dordogne. First, from 1935 to 1959, Louis and Mary Leakey worked on excavations in the Olduvai Gorge, in northern Tanzania, where they discovered the skull fossil they named Dear boy (1959). They considered it a kind of prize, because they had spent more than twenty years digging and had found mostly fossils of animals and primitive stone tools, but this was the first almost complete and so clearly dated hominid fossil. It was an australopithecine (Australopithecus boisei), and this discovery encouraged them to set up a permanent base camp. It was here that, two years later, Mary was to identify the first remains of Homo habilis, the oldest known human fossil, and later, Louis was to discover the first fossils of Homo erectus.

Louis Leakey died in 1972 but Mary continued to work on the excavations they had started together and, from 1974, started new ones in Laetoli, 45 km south of Olduvai, in the Ngorongoro Conservation Area. It was here that she found and described the famous hominid footprints, revealing that they walked upright 3.75 million years ago. In fact, even though she retired in 1983 at the age of seventy, she never abandoned her research on fossils, and remained active until her death in Nairobi in 1996 (Leakey, 1981; 1984).

References

Godayol, P., 2011. Viatgeres i escriptores. Deu perfils. Eumo Editorial. Vic.

Kingsley, M., 2001a. Cautiva de África. Las peripecias de una viajera intrépida. Mondadori. Barcelona

Kingsley, M., 2001b. Viajes por el África occidental. Valdemar. Madrid.

Leakey, M., 1984. Disclosing the Past: An Autobiography. Garden City. New York.

Leakey, R. E., 1981. La formación de la humanidad. Serbal. Barcelona.

Morató, C., 2005. Viajeras, intrépidas y aventureras. De Bolsillo. Barcelona.

Tillion, G., 1966. Le harem et les cousins. Éditions du Seuil. Paris.

Tillion. G., 2009. Fragments de vie. Éditions du Seuil. Paris.