In early November 1572, a new star appeared in the sky. At the time, the Aristotelian worldview held that the heavens were unchanging, so the presence of a defiant star in the constellation of Cassiopeia caused society to mistrust the divine order of the heavens.

The court in Madrid was so alarmed that Philip II commissioned the wisest of his subjects to explain what this unexpected star was. Jerónimo Muñoz, professor of Astronomy and Hebrew at the very young University of Valencia, set to work and wrote the Libro del nuevo cometa (‘Book of the new comet’), in which he detailed at length his studies of the phenomenon. Despite the name of the treatise, he stated that «it looked more like a fixed star than a comet». Muñoz was also a mathematician, geographer, and engineer. This year, the University of Valencia celebrates the fifth centenary of his birth.

So, despite Aristotle’s ideas, the sky was mutable and the new science based on observation was making its way and beginning to surpass the old science. All over Europe numerous astronomers observed and studied the star. The Dane Tycho Brahe, the last of the great pre-elescopic observers, devoted the most time to it.

The celestial wonder caused great curiosity in European enlightened society. It shone brighter than Venus and could be seen even during the day. It should come as no surprise that this extraordinary fact influenced numerous cultural manifestations. For example, the traditional star located over the walls on the coat of arms of Gandía was raised and a tail was added to it, to relate the death of Saint Francis Borgia with the new star that began to shine only 36 days later, as the astronomer Josep Emili Arias demonstrates in a detailed study.

We also find signs of the star in Shakespeare’s Hamlet: it is quoted in the first act, first scene, when the castle guards talk to each other about the ghost they have seen in the last few nights:

BERNARDO.

Last night of all,

When yond same star that’s westward from the pole,

Had made his course t’illume that part of heaven

Where now it burns, Marcellus and myself,

The bell then beating one…

This is the conclusion of Texas State University forensic astronomer Donald W. Olson. The star to the west of the Pole must belong to the constellation Cassiopeia, given that the scene occurs in autumn and at one o’clock in the morning. However, as there are no particularly bright stars, the new star that appeared in November in Cassiopeia perfectly matches the description of the guardian Bernardo.

There were many explanations for the phenomenon, often in keeping with the geocentric and crystalline sphere paradigm. The astronomer John Dee argued that the new star had descended from the sphere of the fixed stars to the sphere of Venus and then returned to its original location. This would explain the sudden stellar appearance, the increase in brightness and the final descent. And Shakespeare echoed this at the end of Act I, scene V.

GHOST.

But that I am forbid

To tell the secrets of my prison-house,

I could a tale unfold whose lightest word

Would harrow up thy soul; freeze thy young blood,

Make thy two eyes like stars start from their spheres,

Thy knotted and combined locks to part,

And each particular hair to stand on end

Like quills upon the fretful porpentine.

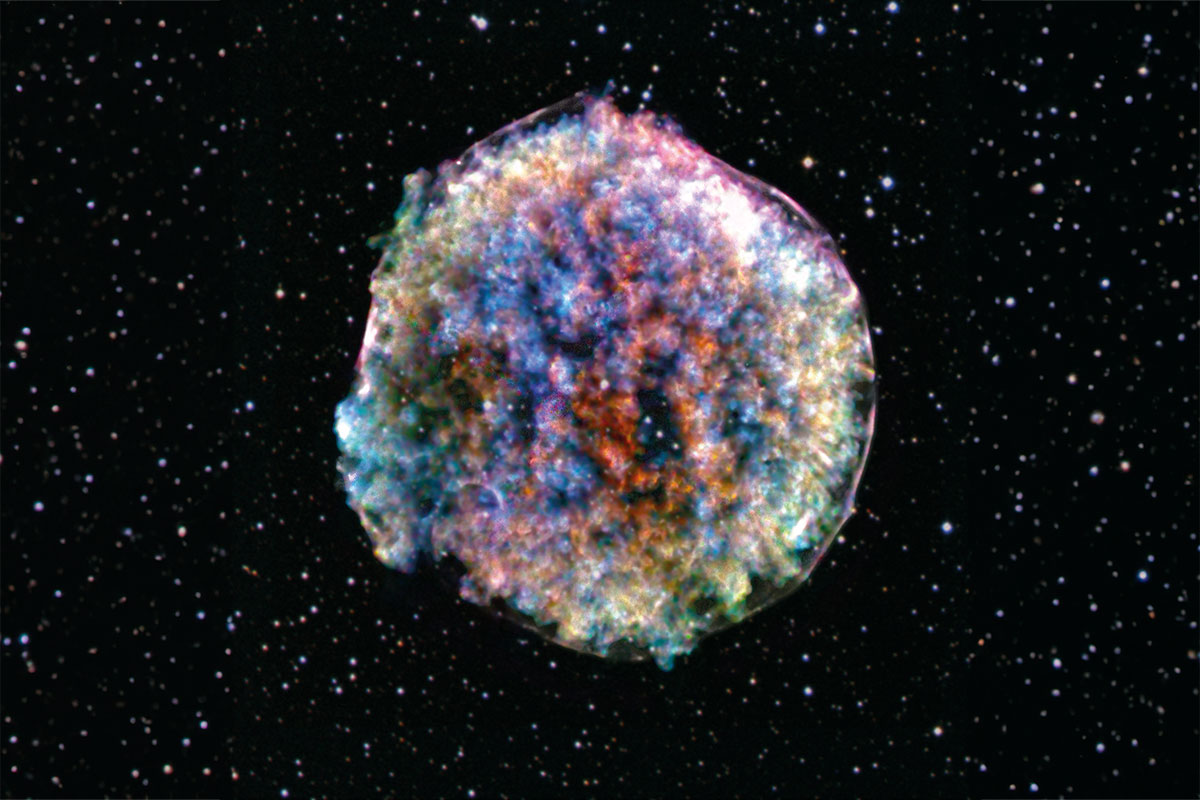

The new star illuminated Europe’s sky for sixteen months during a key paradigm shift. Copernicus had just published De revolutionibus orbium coelestium, in which he proposed a new celestial order centred on the Sun, while new ideas based on reason were gaining ground and banishing the old arguments of authority. We now know that the intense light that shone over Valencia in the autumn of 1572 was the result of the explosion of a white dwarf star in a binary star system some 8,000 light years away, a type Ia supernova. And from that explosion, only a large expanding cloud of gas remains.