Using fire to fight wildfires

Forests, fires and forest management in Catalonia

Forests cover a large part of Catalonia (63%) and this means their management is critical to good spatial planning. Prescribed fires help prevent major wildfires, which have marked recent history, they also help to reintroduce a natural element in the Mediterranean forest: fire.

Forested areas account for 63% of Catalonia. To put this into perspective the European average is 25%, while the percentages of other territories are: Spain 32%; France 27%; Greece 28% and England 15%. Therefore, in Catalonia, forestland is a key consideration when it comes to land management. This high percentage of woodland means there is a need to carefully monitor, study and analyse the forest, and take suitable action to manage it effectively. This is even more important considering the history of Catalan forests, as the intense processes of change and transformation –taking place over the past 150 years– have left wildlands far removed from what a natural forest would be without human intervention.

«The high percentage of forested land in Catalonia means there is a need to carefully monitor, study and analyse the forest, and take suitable action to manage it effectively»

The structure of forest ownership is another interesting point. According to data from the Catalonian Forest Technology Centre from 2008, over 70% of forestland is privately owned. Aware of this reality, the Government of Catalonia created the Centre for Forest Property (CPF), a public company devoted specifically to promoting the planning and management of privately-owned forests. The CPF offers forest owners two technical planning instruments: the «PTGMF» (Technical Plan for Forest Management and Improvement) and the «PSMF» (Simple Plan for Forest Improvement). It must be said, however, that, although the number of forest owners joining one or other of these plans increases each year, there is still a long road ahead. These two planning instruments encompass a variety of management tools, which relate to the goals an owner wishes to accomplish, always on a voluntary basis, because owners are not legally bound to take care of the Catalan wildlands. Thus, these large wildland areas, forests or plantations and multi-ownership, together with forest fires, are among the greatest problems facing the Catalan forest.

Fire and forest management

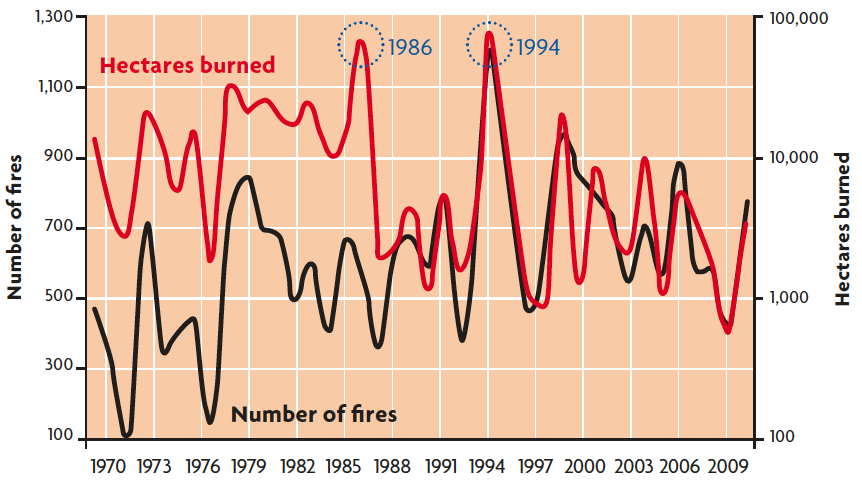

In Catalonia, the change from what is known today as the epoch of major forest fires took place in the eighties. Although fires have recurred throughout history, they had never before reached the magnitude of the 1986 fires, which burned over 60,000 ha, including the area razed by fire on Montserrat mountain. Then followed a number of years with very few forest fires, and had it not been for summer prevention campaigns there would have been the widespread impression that the forest fire problem was history. However, in 1994 the Catalan forests were to witness one of their most tragic moments with fires scorching more than 70,000 ha. In fact 1994 was to become known as «the year of the wildfire in central Catalonia».

This graph shows the number of fires and hectares burned from 1970 to 2009 in Catalonia. 1986 and 1994 stand out as the years with the greatest burned surface area.

Perhaps, at that moment, it was thought to be bad luck rather than problem related, and it was not until 1998, when Solsonès was scorched, did it become apparent that there was a serious and deeply-rooted problem requiring urgent attention. At that time, according to the Support Group for Forestry Projects (GRAF), 0.4% of fires were responsible for 96% of all the burned area. How was it possible that the firefighting services were unable to cope with a forest fire? Perhaps the question in itself could provide the answer. Fire extinction is so efficient that fire fails to burn what is potentially flammable. Therefore, if fire is suppressed efficiently year after year, there is an increase in the amount of fuel ready to feed a huge forest fire. However, this conclusion is not easily reached. This is what is now called the fire paradox: the better we are at putting out fires, the greater the potential wildfires will be when sparked in a high-risk scenario.

Changes in land use and cover

Notwithstanding, this is not the only explanation for this problem. It is common knowledge that in recent decades Catalonia, like many other regions of the developed world, has experienced agricultural land abandonment with the consequent change in land use. This means forests have encroached upon what were once meadows, grasslands, pastures or fields. Not only that, the people who made a living from these pastures no longer use the forest as a fuel source, and thus fuel piles up in the forest, ready to burn.

«In 1994 the Catalan forests witnessed one of their most tragic moments with fires scorching more than 70,000 ha. This year became known as “the year of the wildfire in central Catalonia”»

There is another phenomenon to be taken into account. A fire occurs because the «fuel, oxygen and heat» triangle is completed by a spark. Often this spark is made by someone in the forest, and occurs accidentally, intentionally or by chance. For a number of reasons, more and more people visit woodlands and even build houses there, both first and second homes. Isn’t it becoming rather common to feel you don’t know where the forest ends and the city starts? One should add that probably fires would not present a problem if forests were economically profitable, but currently it is exceptional for forests to provide a source of income and there are more people living in these woodlands but unaware of forest-related economic activities. According to official data, in Catalonia there are over 500 illegal housing developments located in the so-called wildland-urban interface.

After these large forest fires, the time came to think not only about extinction, in other words, how to fight forest fires, but also to consider prevention. In 1999 the Catalan government created the GRAF (Support Group for Forestry Projects) within the firefighting department. This group put forward the idea that firefighters should work not only to extinguish fires but also on year-round prevention activities. They began to establish the idea that fires were «put out» in winter. The GRAF introduced the idea that if they were to fight fire, the first thing was to know about fire. In this respect, history can teach us a great deal and help us to understand why fires behave in a certain way in certain places and situations. This kind of firefighting may be more effective.

Controversial prevention methods: prescribed burning

The GRAF, comprising engineers-come-firefighters devoted to both the prevention and extinction of fires, was responsible for first proposing prescribed burning as a management tool in the experimental stage. Since 1999, fire has been used as a forest management tool in a technique called «prescribed fire» or «prescribed burning». Since then Catalonia has been the only region in the Spanish state to have seriously tried using fire as a potential tool in forest and wildland management and in preventing major forest fires. There are other purposes for which burning has been employed in Catalonia, such as to control unintentional burning of underbrush, for reasons of traffic, grazing, hunting, tourism, or for the practice and training of GRAF members. Controlled burning helps prevent dangerous blazes from breaking out.

A firefighter belonging to GRAF (Support Group for Forestry Projects) lights a prescribed fire. Controlled burning is a way to avoid wildfires, because it prevents the accumulation of potential fuel. / X. Úbeda

The objectives of burning are always very diverse, as diverse as any action taken within an ecosystem. First of all, we should clarify that a burn is not a fire. The main difference is the intensity of the flame, so this factor determines whether the fire benefits or harms the environment. Prescribed burning is based on the practice of low-intensity fire, artificially directed so it cannot spread or develop freely. Prescribed burning follows a previously designed and approved «prescribed burn plan» which clearly specifies the «prescription window», taking into account the weather conditions, topography and available fuel, to ensure burning remains fully under control.

The type of burning prescribed depends on well-defined objectives and can vary depending on whether one target or another is sought. Then according to the conditions established by the prescription window, a particular «ignition pattern» is followed, in other words, a predefined way to start the fire and direct its progression. Burning patterns may vary, however they are mainly based on variations or strategies to drive the fire by a head, flank or tail.

A very important point from the scientific viewpoint is that the GRAF has always allowed research groups to treat the prescribed burns as experimental fields, thus providing a research opportunity. A burn is a scenario where many variables can be controlled which, when known, can be subjected to experimentation. There are several interesting variables to consider: How do burns affect wildlife? What about the vegetation? And the soil? How does the fire behave? Many research groups have taken advantage of this infrastructure scientifically, to carry out fieldwork. Prescribed burns are controversial as not everyone accepts this type of forest management system. Thus, GRAF also encourages research into all aspects of burning. Answers must be given and all the benefits and drawbacks of this type of management should be discussed. Indeed, it is always necessary to find a balance that will help establish a sustainable forest. Nor is the systematic criticism of a forest management strategy valid without proposing an alternative or without in-depth knowledge of the advantages and disadvantages of this strategy.

But we do not wish to advocate prescribed burning as a panacea. In this day and age of global change, global warming and high CO2 levels in the atmosphere, it may seem contradictory to propose a valid management tool that implies the deliberate release of CO2. But just because there are such huge levels of CO2 released by the industrial network, transport, energy… that make up the developed world in which we live, this makes us think that the ancient and natural process of low intensity burning, namely prescribed burning, is counterproductive from the start.

This is where management is essential, and now not only forest management, but the global management of these problems. It is our convenience lifestyle that causes disproportionate amounts of CO2, which we must rapidly minimise if we want to redress the balance. Moreover, from our point of view, prescribed burning should be seen for what it really is: one of several tools available to forest management. It cannot be considered as a universal remedy of widespread and systematic application, as otherwise we would face a new source of CO2 imbalance, released by fire management.

A plot in Tivisa (Tarragona, Spain), before and after a controlled burning event aiming to restore pastures for sheep grazing. After the tender buds sprout, the grazing animals keep vegetation low and reduce the fire risk. / X. Úbeda

A new way of understanding forest management

Strictly speaking, management is defined as the act or manner of managing, handling, supervision, or control. This traditional way of managing forestlands, domineering and abusive and attending to the needs of human beings, should be redefined considering the ecosystem as a whole. As it seems that there will not be a change in economic system in the short or medium term, we must define how to manage forestlands within the neoliberal and production-based economic system in which we live. Thus we could propose a new approach, with more participatory, multi-sectoral and transversal management in the affected communities, taking into account the participation of neighbourhood associations and forest communities, forest owners, administrative departments such as Industry, Education, Planning, Presidency, and so on. However, the Department for Environment should have the last word.

The scientific community should be involved and consulted when establishing the causes, prevention methods and recovery related to fires. Silvopastural systems and sustainable forestry practices should promote combined ecological, economic and social values, taking into account local communities and each and every one of the parties concerned. Rural abandonment should be fought and the value of the intangible services native forests provide should be considered as what we might call «services to the community». These would include the hydrological cycle, carbon sinks, oxygen sources, improved quality of nutrients and soil structures, and reversing the trend in forest fires. All these represent added value produced by the Catalan forestlands, even though they are not rewarded economically in the neoliberal mercantilist economies of today. Finally, we need a forest management plan that promotes an education policy aimed at the general public, helping people to understand and appreciate the importance of environmental resources in general and forestlands in particular.

REFERENCES

Castellnou, M. et al., 2004. «Replantejant-se el futur de la prevenció i extinció d'incendis forestals». In Plana, E. (ed.). Incendis forestals, dimensió socioambiental, gestió del risc i ecologia del foc. Xarxa ALINFO. Solsona.

Galán, M. & S. Lleonart, 2004. «Plans de gestió de grans incendis forestals». In Plana, E. (ed.). Incendis forestals, dimensió socioambiental, gestió del risc i ecologia del foc. Xarxa ALINFO. Solsona.

Martínez, E. & A. Larrañaga, 2004. «Programa de gestió de cremes prescrites a Catalunya». In Plana, E. (ed.). Incendis forestals, dimensió socioambiental, gestió del risc i ecologia del foc. Xarxa ALINFO. Solsona.

Outeiro, L. et al., 2008. «Geostatistical Methods to Study Spatial Variability of Soil Cations After a Prescribed Fire and Rainfall». Catena, 74(3): 310-320.

Piñol, J., 2004. «Acumulació de combustible i la paradoxa de l'extinció». In Plana, E. (ed.). Incendis forestals, dimensió socioambiental, gestió del risc i ecologia del foc. Xarxa ALINFO. Solsona.

Piqué, M., 2004. «La gestió forestal com a eina per a la prevenció dels grans incendis forestals». In Plana, E. (ed.). Incendis forestals, dimensió socioambiental, gestió del risc i ecologia del foc. Xarxa ALINFO. Solsona.

Úbeda, X. et al., 2005. «The Effects of Prescribed Fire on Soil Quality (Prades Mountains, North East Spain)». International Journal of Wildland Fire, 14(4): 379-384.

Vadilonga, T. et al., 2008. «Effects of Prescribed Burnings on Soil Hydrological Parameters». Hydrological Processes, 22: 4249-4256.