Refugees and Stateless Persons

Political asylum and international protection in Spain: trends in numbers and red tape

Border control policies have been strengthened, making Spain – and indeed Europe as whole – a kind of fortress that is becoming increasingly hard to enter and, consequently, to request asylum. The Spanish government prioritises what they call the «fight against illegal immigration» over compliance with the State’s obligations on Human Rights, thus violating the right to asylum and International Protection established under the Geneva Convention on the status of refugees, and elsewhere.

Keywords: refugee, stateless person, resettlement, Geneva Convention, Asylum and Refuge Office.

As a result of the atrocities committed in World War II and the large number of displaced persons and refugees in Europe, in 1951 the United Nations signed the Geneva Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, a document that defines, among other conditions, who qualifies as a refugee. The subsequent 1967 Protocol removed geographical and temporal constraints contained in the Convention and left the definition of a refugee as «A person who owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it». This definition therefore outlines the concepts of refugee and stateless person (person who has no nationality).

«Current Spanish law transposes several European directives and regulations that affect issues related to asylum and international protection»

Article 13.4 in the 1978 Spanish Constitution establishes the legal terms under which citizens of other countries and stateless persons may enjoy the right to asylum in Spain. In that same year, Spain signed the Geneva Convention, but it was not until 1984 when the first asylum law was enacted (Law 5 /1984), it was then extensively modified in 1994 and stayed in effect until November 20, 2009, the time when the current asylum law came into effect (Law 12 /2009). This law, which governs the right of asylum and subsidiary protection, transposes several European directives and regulations that affect issues related to asylum and international protection. Article 16 of Spanish Asylum Law (Ley de asilo) deals with the right to request international protection, stating the following: «it will be non-Community nationals and stateless persons present in the Spanish territory who may apply for international protection in Spain». Thus, the concept of refugee is restricted as compared to that provided by the Geneva Convention. Firstly, it is restricted with regard to nationality («non-EU nationals») – questioned, not only by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) itself but also by other organisations, for leading to a contradiction with the principle of non-discrimination on grounds of nationality –, and secondly, because it is dependent on where the asylum seeker is: «present in the Spanish territory». Although Article 38 of the Law is entitled «Applications for international protection at embassies and consulates» it provides that the ambassadors of Spain may promote the transfer of asylum seekers to Spain to enable submission of the application, but in practice this does not happen. Therefore, requests for asylum are just received either at the border or in Spanish territory, while embassies simply process asylum extensions for the relatives of those people who have already been granted international protection by the Spanish State.

NUMBERS AND TRENDS IN ASYLUM APPLICATIONS

By legally reducing the possibilities of who is able to seek asylum and where, either at the border or in the territory, we are faced with a system of Spanish and European borders that clearly prevents the entry of people from outside the European Union, and that fails to discriminate between who may or may not seek asylum on entering the country. Border control policies have been strengthened and the Spanish State has become a fortress that is increasingly difficult to enter or to cross borders, and this prevents asylum seekers from officially requesting protection, which is the first step in the process.

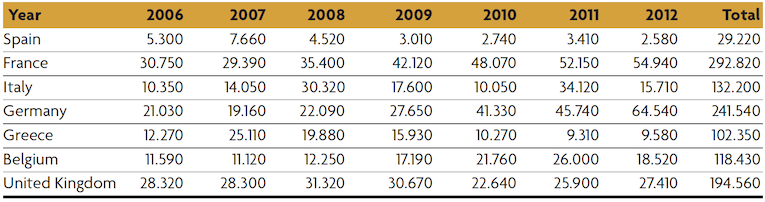

Table 1. Number of refugees per year in several European Union countries. Data from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 2012a and 2012b.

Asylum-application figures differ slightly depending on whether they are provided by the UNHCR, the EUROSTAT (Statistical Office of the European Union), or the Spanish Refugee Office (Oficina de Asilo y Refugio de España, OAR). One explanation for these variations is whether the right to asylum extensions are counted or not, but trends are basically the same: in recent years, and according to UNHCR figures, there has been an increase in the number of refugees in other EU countries such as Germany, France or the United Kingdom, and the figures remain high in countries such as Belgium, Italy and Greece, while in Spain they are decreasing (Table 1).

Conclusively, Spanish statistics are well below European standards in all parameters, not only in the number of applications, which in 2012 hit the lowest figures in the last 25 years, but also in figures granting refugee status and subsidiary protection, which totalled just 20.19 % of the cases. These figures show Spain’s lack of commitment to refugees and their right of asylum.

Taula 2. Table 2. Applicants for international protection in the Spanish State between 2000 and 2012. Data from the Asylum and Refuge Office extracted from CEAR (Spanish Commission for Refugee Aid): 2006-2013.

Red Tape

Successful externalisation of European Union border policies on the southern borders has led to changes in the classic routes of entry into Europe and the Schengen area. Last year it was estimated that nine out of ten people entering Europe did so through Greece. Not only are these policies unable to stop the migratory flows but they also have other consequences, such as the death of thousands of people trying to reach the coasts of Italy from countries like Libya and Egypt, or others who have died on the shores of the Canary Islands, Ceuta and Melilla, or on their way to reach these points, in African deserts or at the hands of mafias. This border control externalisation, in cooperation with the countries of origin, and the migratory transit have meant that the number of boats reaching the shores of the Spanish State has fallen by more than 90 % in the last six years. The numbers of people intercepted while trying to reach Spanish territory were similar in 2012 and 2013 (4,381 and 4,370, respectively), while there was a 15% decrease in arrivals to Ceuta and Melilla in 2012, but a 64% increase in 2013. In short, this has caused a drop in the number of people who have managed to make an application for asylum on the Spanish borders (Table 2).

In the case of Ceuta and Melilla, neither city belongs to the Schengen area, which means that people claiming asylum are not allowed to travel to the peninsula, and therefore have to wait until their request is resolved, in most cases unfavourably. This has led many applicants to withdraw their requests in Ceuta and Melilla, on the impossibility of being transferred to the mainland, which represents another hurdle to accessing international protection. Currently, due to pressure from international organisations and the Ombudsman, the Spanish state has transferred some of the 200 people of Syrian nationality who, fleeing the war in their country, managed to reach Ceuta or Melilla, but still prevents the entry of many more from Morocco or Algeria, waiting to enter.

«Border control policies have been strengthened, turning Spain into a fortress that is increasingly hard to enter»

Pending the publication of the final data for 2013 by OAR, a surge of asylum seekers may be expected in Spain; however, as in previous years, the explanation is not because more refugees have reached Spanish shores, or because there are mechanisms to detect and transfer these people. Rather. this increase reflects, one the on hand, the arrival of people of Syrian nationality, many of whom held a visa issued by the Spanish authorities in Lebanon, or others of the same nationality who already lived in Spain; and, on the other hand, by asylum applications from Mali nationals, most of whom have lived in Spain for years. In both cases, these asylum applications are made by civilians fleeing armed conflict or who cannot return to their country, especially in the case of Syria, where the war is giving rise to millions of refugees and internally displaced persons.

Ceuta and Melilla do not belong to the Schengen area and people who wish to claim asylum there are not allowed to travel to the Peninsula. Consequently they have to wait until the request is resolved, in most cases unfavourably. / Frontera Sur

POLITICAL COMMITMENT AND SUGGESTIONS FOR IMPROVEMENT

The figures in Table 2 show an increase in the number of asylum applications for some years. Once again this is not the result of political improvements in refugee protection or easy access to the procedure, rather it is a result of events similar to 2007 when nearly a thousand Iraqi refugees in Egypt sought asylum to the diplomatic missions of Spain in Cairo and Alexandria. These requests were denied and, therefore, these people were not transferred to Spain. In 2010 and 2011, due to a special agreement signed between the governments of Cuba and Spain and mediated by the Catholic Church, 70 prisoners and their families (379 female and 390 male citizens in all) were transferred to Spanish territory. These people were granted refugee status or subsidiary protection. Even so the above mentioned agreement, fruit of a political commitment, had nothing to do with the ordinary circuits of refugee arrivals, but rather a pact between states. This shows that the reception of refugees is possible if there is greater political willingness.

Resettlement is another possible form of asylum, reflected in the first provision of the Spanish Asylum Act, which involves the transfer of refugees from other countries to Spain, under programmes developed between the government, UNHCR and other international organisations. The law provides that the Cabinet will agree annually on the number of persons subject to resettlement. In this respect, and before the current asylum law, Spain had already resettled refugees; however, after adopting the current asylum law the Spanish government resettled only 17 people in 2010, while in 2011 they approved the resettlement of 80 people who were not transferred to Spanish territory until 2012, and plan to resettle only 30 refugees between 2013 and 2014. These figures are shocking when compared to other countries. In 2012, there were 88,600 refugees admitted to 22 resettlement countries. The countries receiving the largest numbers were: United States, 66,300; Canada, 9,600; Australia, 5,900; followed by Sweden 1,900 and Norway, 1,200. All this shows again that Spain is unwilling to accommodate refugees this way.

«The conditions and treatment of people who reach Spanish ports as stowaways (hidden in ships and cargo vessels) or of those interned in Detention Centres for Foreigners (CIE) are another cause for complaint»

There is another cause for complaint levelled at Spain by the platforms and organisations defending human rights. These concern the conditions and treatment of people who reach Spanish ports as stowaways (hidden in ships and cargo vessels) or of those interned in Detention Centres for Foreigners (CIE), waiting to be returned to their country or to third countries. Regarding stowaways, in 2012 the figures were finally revealed after several parliamentary questions formulated by Izquierda Plural (left-wing coalition). From 2008 to 2012, a total of 978 people arrived, of which 105 were able to land, more than half of them children; however, only five of them managed to seek asylum, which was later denied by the Asylum and Refuge Office. Here we should highlight the fact that these people’s rights to request legal aid is systematically violated, which further hinders their possibilities of being granted asylum. The number of people seeking asylum in Spain who were locked in Detention Centres for Foreigners (CIE) in the years 2010, 2011 and 2012 were 213, 261 and 160, respectively. These requests are handled at the border, which takes less time and, although the Refugee Office does not provide comprehensive data, NGOs specialising in asylum know that the vast majority of them are denied and not admitted. In the meantime, these people are still detained, awaiting deportation.

All these factors together explain the low number of requests made in Spain in recent years. Furthermore, the practices show that the Spanish authorities prioritise what they call «fight against illegal immigration» over compliance with the State’s obligations on Human Rights, thus violating the right to international protection.

Given this scenario, various agencies and organisations defending the right of asylum have made proposals to improve the protection of refugees and their ability to access the asylum application procedures. Proposals include the reform of the Spanish Asylum Act regarding applications made at embassies and consulates, the exclusion of the right of European Union nationals to seek asylum, and improved regulation of the procedures and the status of stateless persons. Improvement is also proposed in the number and quality of refugee resettlement programmes and ensuring access to the Peninsula, or for the people who have made the asylum application in Ceuta and Melilla to be transferred. Other proposals include the creation of advisory committees in collaboration with NGOs for case studies, the recognition of problems related to human trafficking and maras (specialised gangs) in the granting of asylum, greater awareness and specific recognition of international protection for people who are persecuted due to sexual orientation or gender violence, and respect for the right of non-refoulement of persons who may suffer inhuman or degrading treatment in their countries. And, ultimately, there is a call to improve information and overall access to the asylum procedure, which is a fundamental right. Again, it remains to be seen whether these petitions will be heard by policy makers, or fall on deaf ears.

Comissió Espanyola d'Ajuda al Refugiat, 2006. La situación de los refugiados en España. Informe 2006. CEAR. Madrid. Disponible en: <www.cear.es>.

Comissió Espanyola d'Ajuda al Refugiat, 2007. La situación de los refugiados en España. Informe 2007. CEAR. Madrid. Disponible en: <www.cear.es>.

Comissió Espanyola d'Ajuda al Refugiat, 2008. La situación de los refugiados en España. Informe 2008. CEAR. Madrid. Disponible en: <www.cear.es>.

Comissió Espanyola d'Ajuda al Refugiat, 2009. La situación de los refugiados en España. Informe 2009. CEAR. Madrid. Disponible en: <www.cear.es>.

Comissió Espanyola d'Ajuda al Refugiat, 2010. La situación de los refugiados en España. Informe 2010. CEAR. Madrid. Disponible en: <www.cear.es>.

Comissió Espanyola d'Ajuda al Refugiat, 2011. La situación de los refugiados en España. Informe 2011. CEAR. Madrid. Disponible en: <www.cear.es>.

Comissió Espanyola d'Ajuda al Refugiat, 2012. La situación de los refugiados en España. Informe 2012. CEAR. Madrid. Disponible en: <www.cear.es>.

Comissió Espanyola d'Ajuda al Refugiat, 2013. La situación de los refugiados en España. Informe 2013. CEAR. Madrid. Disponible en: <www.cear.es>.

Spain. Law 5/1984, 26 March, Regulating Refugee Status and the Right to Asylum. Official State Bulletin, 27 March 1984, 74: 8389-8392.

Spain. Law 12/2009, 30 October, Regulating Refugee Status and the Right to Asylum. Official State Bulletin, 31 October 2009, 263: 90860-90884.

United Nations, 1951. Convention relating to the Status of Refugees. Geneva, 28 July.

United Nations, 1967. Protocol on the Status of Refugees. New York, 31 January.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 2012a. Asylum levels and trends in industrialized countries. UNHCR. Geneva.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 2012b. Displacement: the New Challenge of Twenty-First Century. UNHCR. Geneva.