As of the nineteen-thirties, some films in Spain probed cautiously into the taboo of the economic migration from the countryside to the city. Florián Rey, pseudonym of Antonio Martínez del Castillo, was an exponent filmmaker of Spanish Second Republic cinema. He made films like Nobleza baturra (1935) or Morena Clara (1936), and two versions of La aldea maldita: one silent in 1930 and one with a soundtrack in 1942. This film relates the story of a family – portrayed as a microcosm and nucleus –, which has to move away from an unyielding Castilla, away from the poverty of dead fields, and enter the «vices» of a gruesome city. The need to return to their origins, to the land and to their roots, represents a return to safety and even to honour.

In Surcos (1951) by Juan Antonio Nieves Conde, editor of the magazine Primer Plano, the fortunes of a family are again presented, this time during the Franco era, as they leave the countryside for the city and fail in the attempt. The film was banned by the regime as it showed the phenomenon of denigration in the course of rural migration, even though the director was a Falangist.

We should also mention La piel quemada (1967), by Josep Maria Forn, which captures the despotism and economic and cultural dearth found in Catalonia at the time. Spanish cinema also became acquainted with some movies like Rocco e i suoi fratelli (1960), by Luchino Visconti, films in which migration occurred within the same country. It was in the seventies that filmography proliferated and Spaniards left their country in search of better luck elsewhere, migrating to places like France, Belgium, Switzerland and Germany. Examples are movies like Españolas en París (1970) by Roberto Bodegas, or Vente a Alemania, Pepe (1971) and París bien vale una moza (1972) by Pedro Lazaga. In the first one, starring Ana Belén as a single mother, a group of Spanish girls survive in Paris as maids or bonnes à tout faire. The director, who left for Paris in 1956, said in an interview that he was running away from black and white film and unreal cinema. And in the iconic and currently acclaimed Vente a Alemania, Pepe a rural Alfredo Landa wearing a beret arrives in a chaotic Munich, following the footsteps of his countryman Angelino, played by José Sacristán, and finds himself with a clashing stark reality that has nothing to do with what he had dreamed of.

This is a film in which political exiles rub shoulders with «serving girls» and has more recently been echoed in films like Un franco, 14 pesetas (2006), by Carlos Iglesias.

Part of Spanish cinema addressing the issue of immigration to Spain has perhaps inadvertently contributed to reinforcing stereotypes about immigrants, especially those of African or Latin American origin. The media has not helped much and often continues to portray immigrants as one of our biggest «problems», continually emphasizing the tragic aspect of immigration and victimization. Films that explore topics and fears of the Spanish towards the African immigrant include Bwana (1996) by Imanol Uribe, a long-time Basque director who has always been interested in social problems (La muerte de Mikel, 1984, or Días contados, 1994). However, in Bwana (an adaptation of the play La mirada del hombre oscuro, by Ignacio del Moral, winner of the 1991 SGAE theatre award) we could speak of an alienating use of stereotype. In this film, a typical lower-middle class family, comprising a relatively young couple (played by Andrés Pajares and María Barranco) travel in their taxi-car from Madrid to a beach in southern Spain for a holiday break with their two preteen kids. They have numerous encounters on this trip, marked mainly by foreigners: two newly arrived blacks to the Spanish coast and a trio of neo-Nazis, whom the viewer deduces to be two Germans and one Spaniard. Ombasi is the only African immigrant to have survived a shipwreck, and who is ultimately left to the fate of the neo-Nazi group. The film provides a particularly interesting view because it arises from the prejudices and stereotypes about blacks that are ingrained in Spanish culture (not only the negative ones but also idealised ones, like sexuality for example). Therefore, these attitudes are the modern heirs of a history of rejection and attraction to the African people. The traditional family is but another link in the chain of this stereotype. Racism is the result of ignorance, as clearly seen in the mother and her views conveyed to her children, perpetuating a xenophobic discourse. It is difficult to identify with these almost grotesque characters but, at the same time, the film certainly addresses familiar and easily recognizable issues, such as the arrival of boats with immigrants, the proliferation of neo-fascist groups, troubled relationships among members of traditional Spanish families and their hypocrisy and cowardice. It was not a box-office hit, although it did rate as the third most popular film on immigration in the nineties, after Flores de otro mundo, by Icíar Bollaín (1999), and Cosas que dejé en la Habana, by Manuel Gutiérrez Aragón (1997).

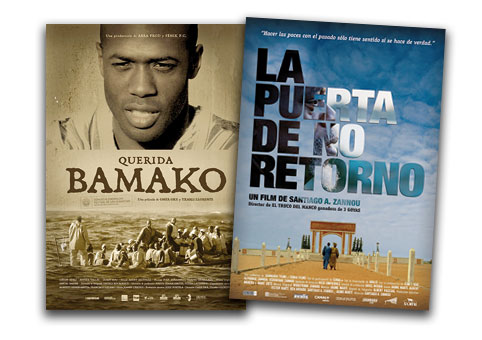

Although it can be said that immigration and the cultural transformations it involves represent an important social phenomenon in Spain, the cultural construction of «travellers» coming from the African continent to Europe has not been dealt with from the immigrant’s perspective as a Spanish movie theme in any depth. Moreover, relating to the fact that it is economic migration, nowadays there is very little literary-artistic-film production as both the first and the second generation are generally very young. The issue of African immigration has been treated with varying degrees of success by Spanish filmmakers, most notably after 1990 we have Montxo Armendáriz’s pioneering Las cartas de Alou (1990) and Chus Gutiérrez’s Poniente (2002) and Retorno a Hansala (2008). However, we should mention the more recent work of directors like Omer Oke, of African origin. In his film Querida Bamako (2007), directed alongside Txarli Llorente, a documentary format is mixed with fiction to present powerful experiences unknown to the Spanish spectator. Thus he creates a collective imagination in which the migrant becomes almost a hero, despite the important message about the costs of this process, especially to human lives. Besides the authenticity, the real-life testimony brings coherence and, at the same time, legitimises the migrant experience. Uncomfortable topics are presented crudely, and at the base of his proposal there exists an educational aim that transcends as much from (pseudo)fiction as in his other documentaries, in which he always deals with issues related to migration in its various stages, such as Trabajadoras invisibles (2008), La causa de Kripan (2009) or OHoun – El tambor (2012). This filmmaker, who was chief of Immigration for the Basque Government, is very socially and politically involved. His aims are to expose Spain’s superficial image of the sub-Saharan immigrant, as a way to respond to the traditional absence in Spanish narrative filmmaking of a solid discourse on otherness or the cultural impact of migratory flows.

«Part of Spanish cinema addressing the issue of immigration to Spain has perhaps inadvertently contributed to reinforcing stereotypes about immigrants»

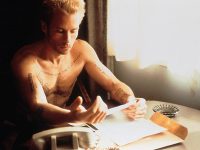

Finally, another director who deserves special mention is Zannou Santiago, born in Madrid in 1977, of an Aragonese mother and a father who immigrated to Spain from Benin in the seventies. With the film El truco del manco (2008) he won the Goya for best young director. In the poignant La puerta de no retorno (2011), where photography and music are particularly important, he also adopts a hybrid form of documentary cinema with aesthetic fiction to give voice to his father, Alphonse Zannou, accompanying him on a trip back to Benin after forty years of absence. In the film, his father will undertake an inner journey to return to his mother’s hometown with wheelchair-ridden Véronique, his only living sister, to collect some soil that he will then place on the grave. It is his way of getting over his feelings of guilt, for what he considers to be a failure: his «failure to return», for his mother and for the corpse still warm with the emotional memory of his origins.