Facing the mirror

Jo Spence and Hannah Wilke

ABSTRACT

Cancer has long been a taboo, an illness surrounded by secrecy, socially silenced and consequently excluded from visual and artistic representation. This article aims to highlight the pioneering role played by two women artists: Hannah Wilke and Jo Spence. In the eighties Wilke and Spence broke away from the fear and shame of cancer to record the disease visually, making it part of their work experience, lived through in the fi rst person. These autopathographic portraits, encompassing different strategies that range from phototherapy to the task of deconstructing stereotypes and taboos or pursuing critical militancy, helped these authors to face this disease personally, and try to unravel the metaphors and stigmas surrounding it socially and culturally.

Keywords: cancer, critical deconstruction, expression of the female gender, growing visibility, self portrait, phototherapy, Hannah Wilke, Jo Spence.

The connections between disease and artistic representation differ greatly and come from long ago. The influence of disease on art can be traced back to ancient times, with amulets and talismans created for healing purposes. But this has not been a benevolent relationship alone; indeed, the portrayal of diseased bodies in the history of art has helped to shape abjection and all that which should be socially stigmatised and denigrated. Another turn of the screw, which is even harsher, comes in the form of stifling taboos, growing around certain conditions that fester in their concealment and their consequent exclusion from representation. Conversely, certain approaches and aesthetic theories have seen disease as a spur to creativity. Awareness of one’s body, pain or reflections on mortality associated with ailments and illnesses give way to depression, leading to the well-known creative melancholy to which Albrecht Dürer dedicated his famous engraving Melancholia I, exploited by romantic theories of art (suffice to say, it was believed that the final stages of tuberculosis were conducive to creation, or that madness played an important role in creativity).

Hannah Wilke. S.O.S. – Starification Object Series, 1974-82. b&w silver gelation prints and 15 chewing gum sculptures mounted on board. / Images courtesy of Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York

«Two diseases like cancer and AIDS have revived contemporary art, which started to take an interest in them towards the end of the last century»

However, coming back to the present – a far cry from romantic approaches – two diseases like cancer and AIDS have revived contemporary art, which started to take an interest in them towards the end of the last century. These two cursed and incurable conditions, which Susan Sontag discusses in her famous cultural analysis of these diseases, are socially plagued by taboos and stigmatising metaphors. A number of artists and writers, who lived through these disease experiences in the first person or very closely, decided to dissect the experience through autobiography, personal diaries and autopathographic portraits. This was true of the work by the American artist Hannah Wilke (1940-1993) and the British photographer Jo Spence (1934-1992), whose artistic production focused on the photographic representation of cancer after having been diagnosed with the condition. In fact Wilke had already made a foray into the subject matter when her mother was fighting against breast cancer. Both were pioneers in making this disease visible, a condition muted and masked for so long, not just in terms of art but also – and more distressingly so – in the social field. These artists implemented various strategies, ranging from critical militancy to phototherapy, using autopathographic portraits to confront the silence and concealment, the denigration and commiseration that Western society employs to deal with diseased bodies, especially women with cancer.

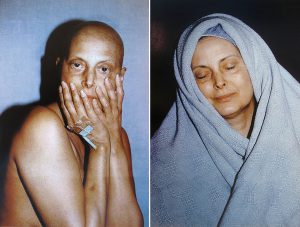

Hannah Wilke. Intra-Venus Series #4, July 26 and February 19, 1992,, 1992. Chromagnetic supergloss prints (diptych), 122,61 x 183,61 cm. / Helsinky City Art Museum, Finland

In this respect, Wilke’s work is paradigmatic since it reveals the importance of gender-related parameters in the physical and psychological experience of this disease. Since the mid-sixties her work focused on the celebration of female physicality (vulva-shaped latex and clay works presaging the vaginal art of the seventies) and she used her own body in a number photographic works and performances. Artworks like the iconic S.O.S. Starification Objects Series (1974) played an ambivalent role between the glorification of women in popular culture and criticism of the oppressive weight that patriarchal society exerts over women, simply for having been born with a particular type of gender difference. In her work, the artist mimics a repertoire of flirty and sexy postures, typical of those adopted by models in adverts; however, she is covered with a series of vagina-shaped «scars» made of chewing-gum. Gender brands individuals, predetermining their position in society in terms of status or power. In the eyes of the most orthodox feminists Wilke’s physical attractiveness was a serious impediment to a critical reading of her work, in fact she was even accused of being narcissistic and of reinforcing objectification of the female body prevailing in Western culture. This reaction to her work changed radically in the nineties, when her Intra-Venus Series was presented posthumously in New York in 1994. She carried out the work after having been diagnosed with lymphoma in 1987, performing a series of drawings and photographs in which the artist is still the focus of attention, but now her body is ravaged by disease. The title (Intra-Venus) refers, on one hand, to Venus, goddess of beauty and love in mythology and Western art and, on the other, to the intravenous medication and feeding she received in hospital.

«Wilke’s work is paradigmatic since it reveals the importance of gender-related parameters in the physical and psychological experience of this disease»

In these pictures Wilke parodies the aesthetic conventions and archetypal femaleness of a beautiful woman, into which she herself had been pigeonholed, but devoid of all the trappings of feminine masquerade. Boldly breaking taboos, she appears without makeup, her body swollen and (in most of them) without hair, adopting poses and gestures of exaggerated femininity. So we see her posing as the femme fatale, a figure both men and women had traditionally linked to the world of art, but bald and with a PIC line piercing her hands on which she rests her face; or looking straight into the camera open-mouthed, alluding to a 1974 piece entitled Gestures, in which her hands make suggestive «holes» in her face, showing it to be a penetrable body, but which in the later work is simply open to being penetrated for medical intervention; or wrapped in a hospital-blue blanket like the Virgin Mary; or Venus-like, naked with a vase of flowers on her head; or sensually frolicking on a white-sheeted bed in a François Boucher style, but with bandages on her buttocks. The look of objectification is doubly paradoxical with her sick body, contaminated and bloated, ravaged by treatment. The illness forced her to distance herself from her own beauty and aesthetic norms of femininity; this distance enabled her to deconstruct the idea of imposing a normative gender identity and, likewise, of a healthy, young and vigorous body. Women with cancer have to face not only physical deterioration in itself but also the loss of two key elements of femininity: breasts and hair. The use of wigs and breast prostheses provides dramatic evidence of Judith Butler’s performativity of gender and also of the healthy body. Gender, sexuality and a healthy body are idealised cultural constructs to which we must respond consistently, and which generate a great deal of anxiety that is magnified in the case of cancer patients. Wilke genuinely exhibits the deterioration of her – once beautiful – body, while simultaneously deconstructing a number of gender stereotypes and representational taboos surrounding cancer, showing herself to be a brave woman who laughs in face of disease and death.

Hannah Wilke. Intra-Venus Series #6, February 19, 1992, 1992. Photography in cibachrome paper. / Helsinky City Art Museum, Finland

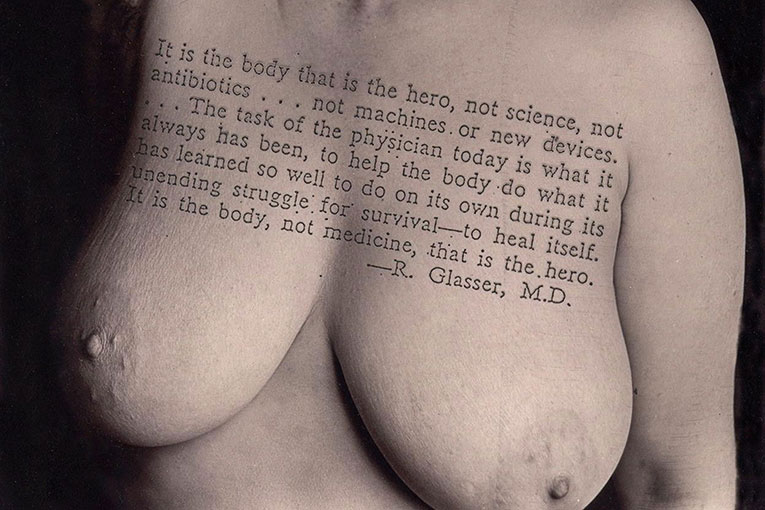

Jo Spence’s work also bravely portrayed cancer through photography, understood in this case as a tool of empowerment and great therapeutic, educational and pedagogical potential. The author, who had been linked to Marxist-rooted militant feminism since the outset of her artistic career, participated in various community-based photo education projects which gave rise to some exhibitions such as Women, Work and Wages (1973-75) or Who’s Still Holding the Baby? (1978) denouncing the situation of women in terms of work, wages or childcare. These projects combined traditional documentary photography with interviews, newspaper cuttings and educational materials in an attempt to inform and raise awareness of the problem addressed. In 1982, when she learned she had breast cancer, the focus of her work changed from social and class-related issues to questions of subjectivity and health, but she never abandoned her aesthetic vision and politically-engaged practice. She underwent a lumpectomy (surgery that removes only the breast lump and surrounding tissue rather than the whole breast) after rejecting the mastectomy recommended by doctors, which she documented in The Picture of Health? (1982-91).

«Jo Spence’s work bravely portrayed cancer through photography, understood in this case as a tool of empowerment and great therapeutic, educational and pedagogical potential»

In this project, as in her earlier work, she set out to empower viewers on a subject rarely dealt with – if not silenced – sharply criticising the social representation of the disease, visions of the healthy body desirable to women, and the medical institution. First of all she conducted extensive research into various cancer treatments and discovered that the medical institution assigned patients to trials, to experiment with various treatments. To her astonishment she found herself on a secret list of people singled out to conduct clinical trials. What is more she found out there were a number of less aggressive alternative treatments, which she then disseminated through lectures and articles in a bid to inform, educate and promote patient empowerment. This project grew out of her own experience as a patient and the feelings she experienced on being treated by the medical system and its protocols. Before her operation she felt like an object, impersonalised, branded, deprived of any voice and infantilised. In one of the photo shoots the artist appears wearing a hospital gown and cap, about to enter the operating theatre, sucking a dummy or her thumb as if she were a baby. Other photos – also humorously caricaturing the reductive stereotypes imposed by social perception of the sick – show the patient as heroine or victim; winner or loser; morally strong or weak – an image of Manichean dichotomy.

On the left, Jo Spence and Terry Dennett. The Property of Jo Spence, 1982-86. Belonging to The Picture of Health?Above, Jo Spence i Terry Dennett. 15th October, 1984, 1984. Part of The Cancer Project.

On the rightA la dreta, Jo Spence i Terry Dennett. Crash Helmet Portrait, 1983. Belonging to The Picture of Health? / The Jo Spence Memorial Archive, London

The photo series documenting her lumpectomy is reminiscent of the crime-scene photographs systemised by Alphonse Bertillon in the nineteenth century. In the 15th October, 1984, photographs, the author appears in a mug shot and sideways on, her headless body decrying the lack of humanisation in the treatment patients receive and their anonymity in the medical system. The image shows her chest pitted by scars, while in her hand she holds a sign showing the date on which it was taken and the state of her body at that time. The author draws an analogy between photographs of criminals and of the sick: the patient’s body is measured, recorded and filed, just like a criminal’s. In some of her last works, like The Final Project (1991-92), she superimposed images; for example in Decay Project I, 1984 (1991-92) she projected a cracked decaying surface onto old photographs of her body – taken in the eighties –, conveying the melancholy flight of time and preparation for death Looking Death in the Eye (1991-92), follows the same lines, superimposing a skull – the image of death – over a self portrait, in such a way that their eyes coincide.

Bibliography

Dennett, T. et al., 2005. Jo Spence. Más allá de la imagen perfecta. Fotografía, subjetividad, antagonismo. Macba. Barcelona.

Hannah Wilke Collection & Archive. <www.hannahwilke.com>.

Le Breton, D., 1999. Antropología del dolor. Seix Barral. Barcelona.

Sander, G., 1988. Disease and representation; Images of Illness from Madness to AIDS. Cornell University Press. Ithaca.

Sontag, S., 1996. La enfermedad y sus metáforas i El sida y sus metáforas. Taurus, Madrid.

Sontag, S., 2007. Bajo el signo de Saturno. Debolsillo Ediciones. Madrid.

Spence, J., 1995. Cultural Sniping: The Art of Transgression. Routledge. London.

Wilke, H., 1995. Intra-Venus. Ronald Feldman Fine Arts. New York. Wilke, H., (1940-1993), 2006. Hannah Wilke: exchange values. Artium. Vitoria.