Suzanne Davit (Paris, 1897–Barcelona, 1973) is little known and studied, despite the relevancy of her legacy to the Catalan botanical illustration of the early and mid-20th century. Great botanists such as Pius Font i Quer greatly valued her unique way of capturing nature. As a woman and an artist who was passionate about nature and who was also scientifically very curious, her representation of plants was different from the typical work of the time. Her innovations are interpreted as an alternative artistic discourse to the dominant patriarchal dialogue and a manifestation of the female touch. Access to unpublished documents – Davit’s correspondence with a friend – has made it possible to reconstruct some of the key aspects of her work, involving the crossroads between the aesthetic exaltation of flowers and a gender perspective.

Keywords: Suzanne Davit, botanical illustration, nature aesthetics, gender perspective, epistolary sorority.

A life in the 20th century: modesty and perseverance

Suzanne Davit, née Suzanne Luddoneau, devoted herself, body and soul, to the study and artistic representation of nature. In her own way, she lived intensely in a world marked by two world wars, the Second Spanish Republic, and a devastating totalitarian regime.

She was born in Paris, where she studied art at the Académie Colarossi, among other important artists, including the Catalans Isidre Nonell and Anglada Camarasa. In 1917, at the age of 20, she arrived in Barcelona with her husband, Dicran Davit, an Armenian-born engineer. The couple soon built up a rich social network, which gave Suzanne access to the city’s enlightened and cultural circles and later helped her survive as a widow. During the 1930s, she took an active part in group exhibitions at the Group of Catalan Watercolourists, Galeries Layetanes, Sala Parés, and the Barcelona Picture Gallery, among others. As far as the years of the war are concerned, there is a gap in our knowledge. According to what her letters tell us, it is very likely that the couple took refuge in Aranese lands, where Davit spent long periods after her husband’s death in 1945. From that time onwards, she felt a close bond with her adopted land and town and became a member of the Hiking Club of Catalonia.

In the 1950s, her activity as a scientific illustrator intensified and she joined the staff of the CSIC (Spanish National Research Council) at the Institute of Marine Sciences, where her important work on marine fauna is still displayed to this day. In 1956 she was appointed curator of the Botanical Institute of Barcelona, a post that allowed her to comfortably retire until her death in 1973.

Davit was curious, eager for knowledge, and came into botany through art, in a self-taught way. She was very methodical and fixed in her habits and became very professional in a highly demanding job, observing, studying, and illustrating plants, mushrooms, and fish. Despite her many friends and acquaintances, she worked in a private and guarded manner and avoided people who asked questions. We know that she did not like to be photographed and as a result there are barely any pictures of the artist.

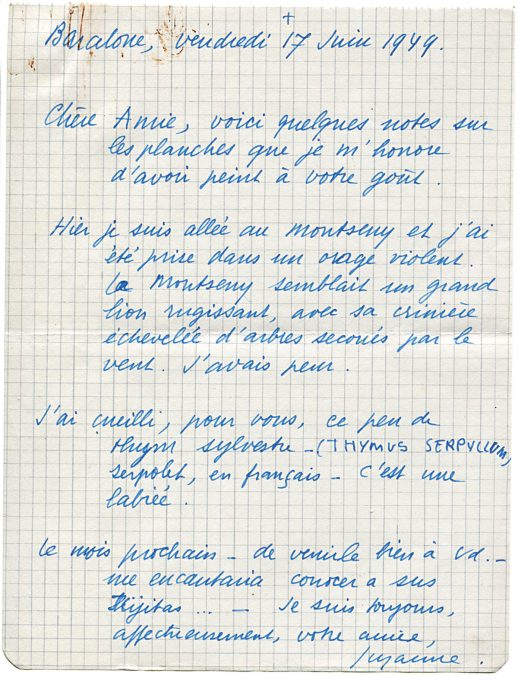

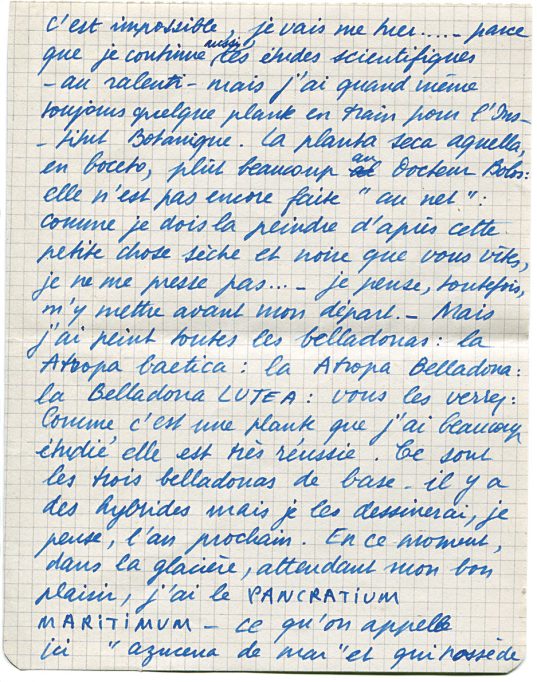

Figure 2. Letter by Suzanne Davit, Barcelona, 17 June 1949. The illustrator’s letters include, in addition to personal comments and confessions, scientific data and botanical references. / Elisa Canela family archive

Despite the lack of documentation, we must also make special mention of the exhaustive monograph on Davit published in 2007 on the occasion of the exhibition «Suzanne Davit. Una il·lustradora a l’Institut Botànic» at the Botanical Institute of Barcelona (IBB), curated by the commissioner and scientific illustrator Carles Puche (Puche et al., 2007).

Epistolary sorority

Reading Suzanne Davit’s letters to her young friend Elisa Canela (1918–2018), we find that she used them as a romantic confession medium, but she also included scientific data. The correspondence began in the mid-1940s and continued until the year of the illustrator’s death. The first letters were more formal, but later a more intimate correspondence would develop in which we can glimpse a strong sense of friendship and sisterhood between two women who lived beyond the limits of the conservative society of the time. The letters were written confidentially and in the style of a personal diary, mainly in French, but also switching very organically to Catalan and Spanish. The medium was always the same: pages torn from a Henry notebook. Indeed, her multilingualism reflects the author’s cosmopolitan character.

Many of these letters were sent from Barcelona or delivered directly to the mailbox of a friend that lived a few streets away from her home. This shows that the correspondence became more intimate, allowing them to share all kinds of information and personal concerns. Their epistolary relationship is probably the answer to the need to go unnoticed in Francoist society, where women were constantly undermined and silenced.

The letters chronicle her travels, excursions, and stays in the countryside, as well as aspects of her profession and artistic work. But what is remarkable about them is that nearly all of them contain some well-documented botanical references (Figure 1).

Stays in nature: sources of inspiration and knowledge

Yesterday I went to Montseny and was caught in a violent storm. The Montseny looked like an enormous roaring lion, with its mane of trees shaken by the wind. I was afraid. (Suzanne Davit, Barcelona, 17 June 1949) (Figure 2)

The exaltation of nature in her writings conveys, on the one hand, the pleasure of witnessing its powerful and alluring beauty and, on the other, fear at its uncontrollable hostility. Davit poetically describes these sublime moments when nature displays its greatness, when natural beauty is ephemeral, immeasurable, and difficult to define.

That went well. If I was melancholic, the madness of my work has comforted me, it has encouraged me to work even harder. The contemplation of the great and small things in nature has always made me happy. (Suzanne Davit, Corbera de Llobregat, Fonda Pujol, 4 January 1953)

Throughout her life she made, periodically and without interruption, many excursions and retreats in the countryside. Some of these excursions were connected with invitations she received from friends and acquaintances, such as Maria Estalella, widow of the artist Joaquim Mir.

On Sunday I might go to Corbera: my friends are there and I would like to go to sleep under an olive tree: it is my great inebriation […]. (Suzanne Davit, Barcelona, 8 August 1951)

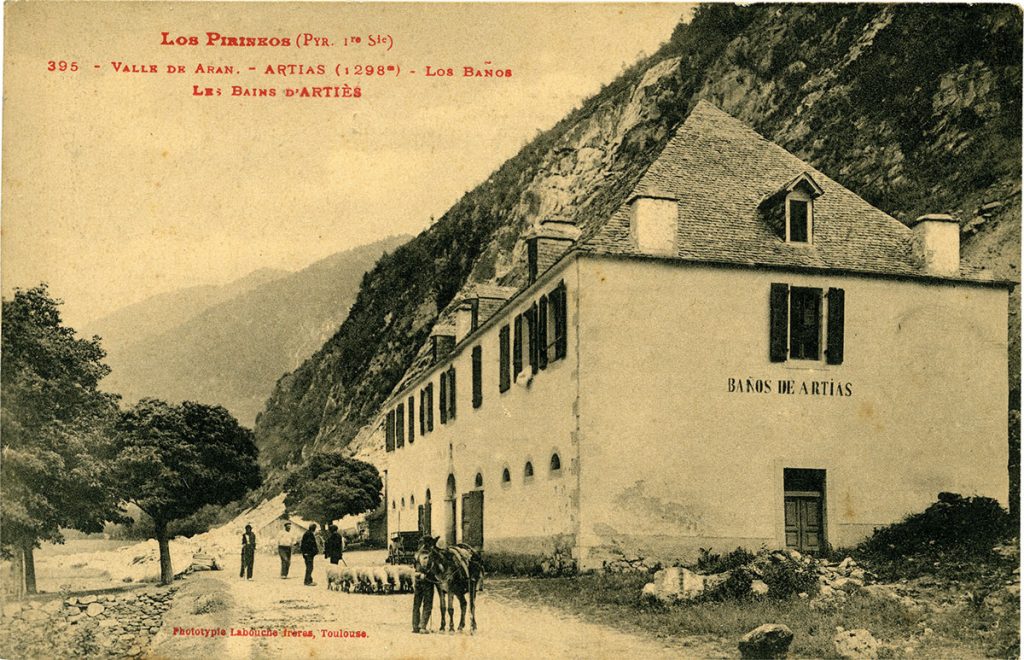

Figure 3. Postcard from the Arties baths, one of Suzanne Davit’s favourite places, from the first decades of the 20th century. / Àngel Romo archive

The most important retreats she is known to have made were on her own, clearly aimed at appreciation and recollection. Here, nature became a balm for the artist, a sort of escape from everyday life, a way of getting away from traumatic events and troubles that were still very much in her mind, as she wrote in relation to a trip to Paris that she was planning:

Before leaving, I must go to Corbera to sunbathe, to look good for my parents, even though they will find me terribly changed, because I have been through the most painful ordeal of my life. Except for hunger, I have gone through everything, and I thought I had reached the bottom of human despair. (Suzanne Davit, Barcelona, 8 August 1951)

However, she had some favourite places to which she always returned, such as the baths at Tredòs and Arties (in the Vall d’Aran region), Xalet de la Molina, and Fonda Pujol, in Corbera de Llobregat (Figure 3).

I have just enjoyed hours of intense happiness: the contemplation of nature is an endless source of infinite satisfaction. A sheet of paper, some colours, and my spirit forgets about the earth and its servitudes. (Suzanne Davit, Corbera de Llobregat, 3 February 1952)

We previously thought that she had limited herself to studying and collecting during these excursions. Davit was not a great hiker, she could not walk very far and moved slowly, and always brought a walking stick with her (she had a good collection with handles she had modelled herself). In fact, in a letter sent from Paris in 1951, she explained that, according to the diagnosis made by a doctor, she may have had polio not long before, rather than the polyneuritis she had previously been diagnosed with, with her difficulties being the result of the former disease.

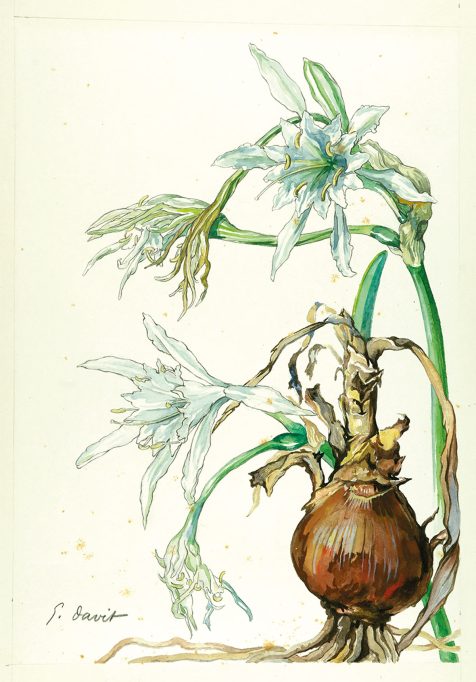

Figure 4. Suzanne Davit, ‘Pancratium maritimum’ in flower, gouache, 21 × 30 cm. / Institut Botànic de Barcelona (CSIC) – Ajuntament de Barcelona

She was a great connoisseur of the flora of the Aranese Pyrenees, thanks to her long stays in the area. From her letters, we can deduce that Davit and her husband spent the six years of the war in these regions. It is important to note that the following letter is the only one in which a fragment has been removed, probably out of concern for the information it contained.

[…] I know, or rather, I think I can describe the entire Aranese valley VERY WELL. I was there for six or seven years and, when my husband died, I stayed there for eleven months, in two periods. That’s where I carried out almost all my studies of Pyrenean flora, for the Portuguese-Spanish Pharmacy Conference. […] my husband could not conceive of life without a stay in Lushon: it greatly benefited his health and were it not for the turmoil of the wars, which suppressed everything, perhaps his end would not have been so premature. (Suzanne Davit, Barcelona, 30 August 1951)

It is interesting to note, therefore, that the stays in nature that we have discussed so far are clearly different from her journeys to France, and specifically to Paris. In the Pyrenees, the approach to nature was more existential and accompanied by an absolutely poetic perception, while Paris represented a cultural stimulus that would help her to develop her artistic research and to acquire the technical knowledge that would later enable her to become a high-level professional.

Art and science: profession and recognition in the scientific field

Although her collaborations and commissions from scientists – such as Karl Faust (1874–1952) from the Marimurtra Botanical Garden in Blanes, and Pius Font i Quer (1888–1964) and Antoni de Bolòs (1889–1975) from the Botanical Institute of Barcelona – had probably started before the war, it was not until April 1952 that she obtained a stable job with the CSIC:

[…] I follow the formula from botany studies: a number of sheets per year and the specimens are brought home to me. (Suzanne Davit, Barcelona, 26 May 1952)

It is interesting that, despite the long-awaited recognition of her work in the scientific field – which allowed her to live independently and enjoy a discreet pension until the end of her life – her artistic activity was clearly differentiated from her scientific work.

Yesterday I finished the works for I. B., and Dr. Bolòs […] came here. He was very appreciative […]. The illustrious Dr. Font will come tomorrow and I am trembling in wait of his verdict, because he is always very rigorous and does not make any compromises in accuracy. Then I will be able to throw myself into pure art work, because what I really want is to have an exhibition with the artists of Gràcia for the festivities – given that I am a Gracian, in fact and at heart. (Suzanne Davit, Barcelona, 16 July 1952)

Figura 5. Letter by Suzanne Davit, Barcelona, 8 August 1951. / Elisa Canela family archive

Both jobs required many hours of dedication and concentration. This responds to the craftsman’s ideal «to do something well for its own sake», which «explores these dimensions of skill, commitment, and judgment in a particular way», and does so with a close connection between the hand and the brain (Sennett, 2009, p. 21). In this sense, as a determined person who got involved in her craft and concentrated completely on it, she was a femina laborans and put a part of herself into everything she did, in other words, she did things with what the classics called meraki.

I need to work for a bit on my art documentation, which I’m constantly «pecking at». Whenever I have illustration or composition commissions (or jobs), I open my study notebooks… – but they are becoming poorer: little by little I have been using almost everything and the time is coming when I will have nothing left to sip from, hungry bee that I am. I will need a month in Corbera, in May, and a stay in Bohí, spending eight to ten hours a day drawing, and then everything will be in order again. (Suzanne Davit, Barcelona, 26 May 1952)

A burst of colour: creative processes

We have very little information about the creative process behind Suzanne Davit’s illustrations. We have been handed down neither notes nor sketches or any procedural documentation. In all her correspondence she referred to the study notebooks only once (the occasion cited above) and it seems that she was not talking about field notes, but rather about art resources. Another significant feature is that none of the botanical explanations in her letters were ever accompanied by any drawings to illustrate the specimens she described.

The absence of field notebooks makes us think that she drew directly from nature. Proof of this are her stays in the Pyrenees and, on the other hand, her preference for obtaining recently-picked live plants – or having them delivered home – so that she could paint from fresh material, which often withered in the process.

That dry plant, in sketch, really pleased Dr. Bolós: it’s not «tidied» yet: since I have to paint it from that small, dry, black thing you saw, I’m in no rush […]. Right now, in the fridge, I have a Pancratium maritimum waiting for me – here they call it a sea anemone, and it has such a sweet fragrance. (Suzanne Davit, Barcelona, 8 August 1951) (Figures 4 and 5)

She probably possessed an eidetic memory, which allowed her to capture and retain all the details she observed without interference. This would also explain her use of the quick and precise gouache technique. Creating the illustrations required absolute concentration, which is why she always worked without an audience or distractions. We know that she did all her work behind closed doors, either in her study at home or in the privacy of an inn room (she always asked for the same one):

I spent three days in Corbera: a small monastic cell where I work so well. When evening falls, I wander aimlessly around the countryside. (Suzanne Davit, Barcelona, 1 February 1957)

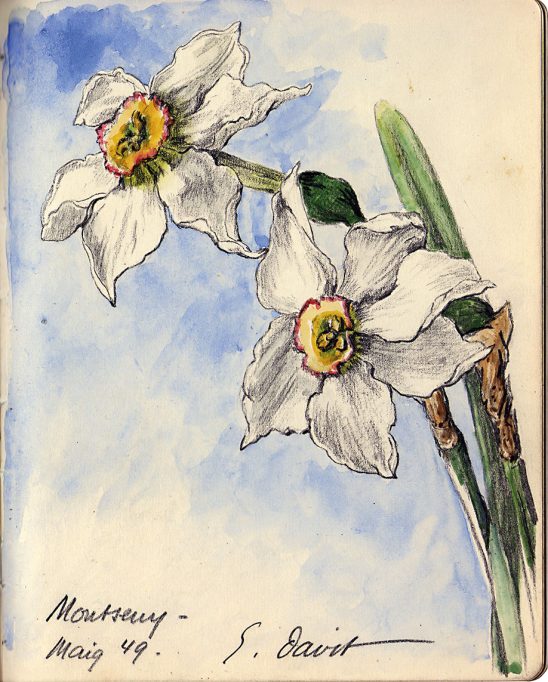

Figure 6. Suzanne Davit, Narcissus, Montseny, May 1949, mixed media, 12 × 16 cm. The use of a graphite pencil in the drawing provides a quality that reminds us of lithography. / Elisa Canela – Album of dedications

Her flat on what was then called Avinguda del Generalísimo Franco, in Barcelona, faced the corner with Carrer del Bruc. The house was a sort of «natural science cabinet», with tables and shelves covered in collections of pine cones, snails, roots, fossils, etc. There were bouquets of flowers and dried plants everywhere:

Your flowers light up the great hall, arranged in an Elizabethan vase […] their perfume invades everything: even the table in my study, with a light, delicious perfume. (Suzanne Davit, Barcelona, 18 May 1952)

Throughout her writings we find an infinite number of poetic appreciations of colours, the fruit of her extensive knowledge of the pictorial palette:

[…] But in the morning, everything calmed down: the sky was cerulean, the sun was shining, and the almond trees were in bloom. (Suzanne Davit, Corbera de Llobregat, 3 February 1952)

Likewise, the artist became interested in the chemical phenomena behind colour changes in plants and studied them extensively (she added in the letter), thanks to the article «Autumn colours» (Pearsall, 1949).

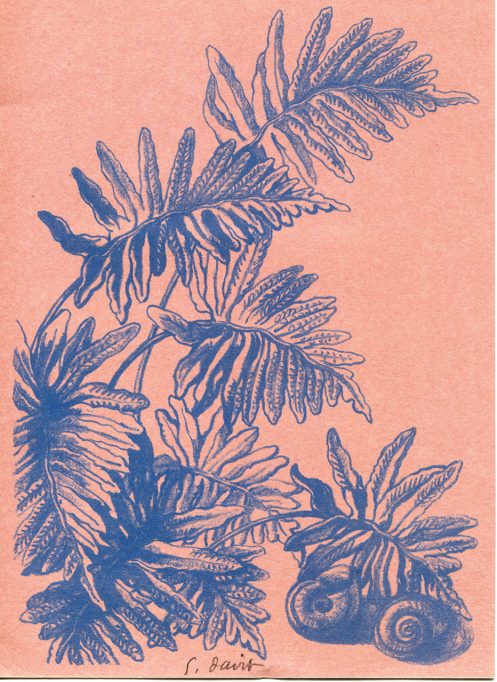

The use of graphite pencils in her notes, like in the Narcissus (Figure 6) – which we can find in the album of dedications – has a pictorial quality that reminds us of lithographs, a technique that occupies an especially relevant place in her artworks (Figure 7). In autumn 1951, she spent a long season at her sister’s home in Paris, where she attended a lithography workshop every morning.

When I do some lithography work, I will gladly show you what little I know. It is a noble art for which I feel a real passion. My dream is to one day be able to buy a press and do all the necessary manipulations at home. (Suzanne Davit, Barcelona, 30 August 1951)

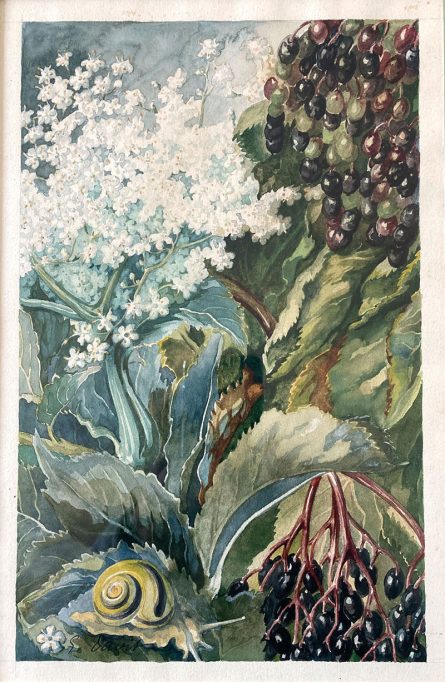

Her palette was very personal, with sober and deep colours, and her meticulous layering and glazing technique gave her works great density. The saturation of colours increases the naturalistic feeling. The composition is designed to capture the observer’s visual attention, sometimes with different focal points; there are no microscopic or micromorphology observations, given that everything is done on its actual size.

Her compositions remind us of still lifes. A Baroque vanitas is ever-present, with decaying organic elements that accentuate the idea of the passage of time. Because of all this, the living plants represented show a great level of expressionism.

Figure 7. Suzanne Davit, Laforest family carol, 1959, blue ink lithograph on cardboard, 15 × 21 cm. In the autumn of 1951, she spent a long period at her sister’s house in Paris, where she attended a lithographic workshop every morning. / Elisa Canela family archive

Her paintings are beautiful and very natural because she used a particularly direct approach. She did not take on a scientist’s cognitivism, scrupulously dissecting each of the parts. Without a magnifying glass, she used a «virtual sentimental zoom» to obtain a virtually photographic image, sometimes partial, of what she was interested in highlighting.

In a certain way, in Suzanne Davit’s illustrations, the plants break the established frame of reference that female illustrators had to tiptoe around in an androcentric scientific world. In addition, far from serving as a purely ornamental theme, they outline a poetic, but also scientific story that jumps out of the intended framework (Figure 8).

Flowers and women: botany in a female spirit

In recent centuries, women have made important contributions to the field of botany, which in most cases have not been recognised, meaning that they are still unknown today. Evidence of this is the very few female names present in the Linnean index of plants. Maria Sibylla Merian, Johanna Herolt, Emily Dickinson, Elisabeth Blackwell, Marianne North, Rosa Luxemburg, and Hilma von Klint are some of the women who approached the world of plants as amateurs from other areas of knowledge such as painting, poetry, medicine, spirituality, etc. All of them created and illustrated their own herbariums.

In fact, from the 18th century onwards, botany became an acceptable discipline for female practitioners. The epistolary genre was adopted to instruct women in the culture of botany, as was the case with Lettres élémentaires sur la botanique (1771–1773) by Jean-Jacques Rousseau. But the discipline would also become an intimate channel of knowledge exchange between women. For instance, An introduction to botany, in a series of familiar letters (1796) by Priscilla Wakefield was the first botany textbook using the Linnaean system and written by a woman, and broke the convention of previous manuals of medicinal plants.

Most of these women lived in cultured environments with a family favourable to the study of natural sciences. The support of a male figure, whether it was their father, brother, husband, or mentor, also played an important role. They often lived outside the domestic bondage of marriage and with no family ties, which allowed them to devote themselves to exploration, adventure, science, and art. In a way, they represent the untamed nature of empowered women, trying to stay out of patriarchal control. Freeing themselves from male protectionism and exacerbated androcentrism meant developing their vocation and dreams. In spite of all this, their work as naturalist illustrators continued to be subjected to male supervision, as was the case for Suzanne Davit with botanists Antoni de Bolòs and Pius Font i Quer, from the Botanical Institute of Barcelona. Therefore, women’s search for beauty was ingrained in a context in which scientific circles were still exclusively male.

Figure 8. Suzanne Davit, Sambucus nigra, 1949, gouache, 17 × 27 cm. Elisa Canela family archive. In the artist’s illustrations, plants do not serve merely as ornaments, but outline a poetic as well as a scientific narrative. / Elisa Canela family archive

Suzanne Davit was one of a few cases in Franco’s post-war Spain, but we must also mention that of Paula Millán Alosete (1899–1979). With the death of her husband, she had to survive without male protection. With no family ties and a marked cosmopolitan spirit, she acquired botany, mycology, and zoology knowledge in a self-taught manner. She preferred travelling alone to have as much autonomy as possible and to create her illustrations in the natural habitats of wild plants. Davit also built botanical visual narratives of the Pyrenees mountains, considered an unknown mountain range from a naturalistic point of view. She provided an Edenic description and visualisation, with sensory images that emphasised the plants’ vitality and beauty. Davit’s work stands out from the traditional botanical illustration resources, in terms of both visual discourse and technique. The use of gouache, an uncommon technique in the scientific field, allowed for a visceral burst of colour in her paintings. In addition, she broke the frame of the plants she illustrated to introduce us to their evolutionary environment, which is to say, to the species living with it. She achieved this by staging a reconstruction using native materials. Therefore, there was a deep knowledge of the locations: idyllic places where she could carry out her fantasies of scientific exploration, sovereign identities, and profound personal longing.

«Botanical illustration is an art form deserving of more complex readings than it has so far received» (Dyson, 2003). More careful research and analysis would be necessary to investigate the complex interactions this type of illustration has with its social context. Indeed, the botanical art of a number of female naturalist artists with a wide background can be understood not only from the point of view of objective science, but must also be read through the subjectivity of their gazes. Suzanne Davit’s work helps us enjoy the beauty of plants. It exudes a unique artistic sensibility towards the natural world around us, and especially of the static living beings that so often go unnoticed.

Note: Among the different publications illustrated with Suzanne Davit’s works, we must highlight those by Pius Font i Quer: Plantas medicinales (Font i Quer, 1973) and Botánica pintoresca (Font i Quer, 1958).

References

Dyson, J. (2003). Botanical illustration or flower painting: Sexuality, violence and social discourse. Colloquy, 7. https://www.monash.edu/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/1768379/dyson.pdf

Font Quer, P. (1958). Botánica pintoresca. Ramón Sopena SA.

Font Quer, P. (1973). Plantas medicinales: El dioscórides renovado. Labor.

Pearsall, W. H. (1949). Autumn colours. Endeavour, 8(3), 157–162.

Puche, C., Puche, C., Romo, À., & Susanna, A. (2007). Una il·lustradora a l’Institut Botànic de Barcelona. http://hdl.handle.net/10261/112038

Sennett, R. (2009). El artesano. Anagrama.

Acknowledgements

Elisa Canela preserved 70 letters by her friend Suzanne Davit. Later, they were archived by her daughter Pilar Viladomiu Canela, to whom we would like to thank for access to and translation of the texts. This article used only fragments of the letters from the 1950s.