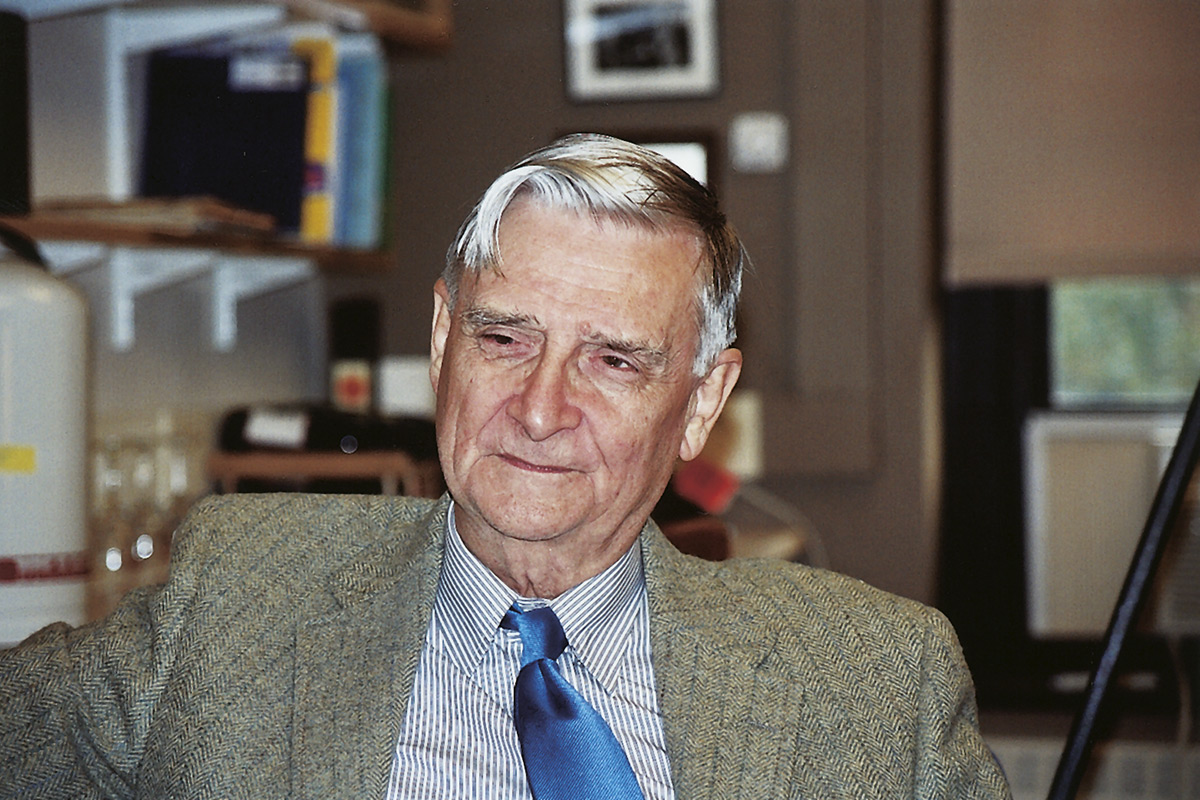

Interview with Edward O. Wilson

Sociobiologist and author of works such as Sociobiology or On human nature

(The following text is only a summary of the full interview published in Spanish and Catalan)

Edward O. Wilson has been fascinated by nature ever since he was a child. He cannot imagine anything more amusing or appealing than the study of the complexity of any ecosystem on Earth. Some years ago, when he was a lecturer at Harvard University, Wilson used to tell his students to go for walk in campus and take a look at the ground. He wanted them to witness the battle between two ant colonies, for instance. “Only a handful of dirt from any of the roads or gardens in campus contains more than a thousand different species”.

Nowadays Wilson is Emeritus Professor at Harvard University and honorary curator in the entomology department a Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology. Wilson is glad he no longer has to teach because he needs time for his writing and to boost his task at the two organisations he belongs to —Conservation International and Nature Conservancy.

Your book Sociobiology was a point of inflection for the evolutionist thought. Although in some sections it is very technical book, it is an easy book to read. Similarly to Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, it is an accessible book to a wide readership…

I am glad you see it that way. (Smiling pleased)

«Some said that any idea that referred to the biology of human nature would result in racist and sexist ideas, but it never happened»

You combine research and popularisation of science ever since you began your work…

This is only partly true. In fact, I almost exclusively did research until I wrote Sociobiology, and by then I was already 46. While I was writing Sociobiology I realised that I had to write in an appealing way for scientists from many different fields, including experts in humanities and social sciences. That is why I focused on an accessible writing with an easy language that included examples and illustrations such as pictures, drawings and the like.

It was afterwards, when I wrote On human nature, that I decided to write for a wide readership. I thought it was necessary due to the controversy Sociobiology had caused. The mass media habitually discussed it, but people were confused and then I thought I should address to a wider readership regarding human sociobiology. It is noteworthy that the sections in my book that dealt with animal sociobiology, that is, a 90% of it, were never controversial. It was welcomed by the scientific community. When I wrote on humans I became involved in a political and theoretical debate. On human nature was a awarded with a Pulitzer prize, and that encouraged me to write more books addressed to the general public. However, I don’t do it very often. Most of the books and articles I write are addressed to scientists.

This work was banned for some time in some communist countries, including the USSR.

Yes, I know, and I cannot understand why.

Maybe your ideas were far too clear, and advocated for a too selfish conception of human kind and nature…

Not at all. I think that many theoreticians from socialist states were against my book because it contradicted the Marxist ideal, better still, Neomarxist ideal, that stated that the human brain is a blank page, easily malleable and that there is no such thing as human nature. For decades socialism believed that there was a better political and social organisation —the form of organisation adopted by socialist states, of course— and that it was necessary for people to adapt to it. Sociobiology points towards a completely different direction. Human nature does exist, and we can find its origins in the history of human genetics. Societies must adapt to this nature and not the other way around. Back then they said, both in Europe and the USA, that any idea that referred to the biology of human nature would result in racist and sexist ideas. However, that simply did not happen. Even though Sociobiology became a quite successful book, it was never used to support neither racist nor sexist attitudes.

«I think that a great deal of the problem lays on the fact that biodiversity is something hard to understand compared to other environmental problems»

Another American science writer was Stephen Jay Gould. It is very interesting that he was also an evolution theorist but opposed most of your views. What do you have in common? What do you disagree in?

Most scientists involved in evolutionary biology are opposed to some of Gould’s ideas. I agree with a British geneticist that once said that Gould’s problem was that his work was misleading, that it was only valuable from a journalistic point of view. He never made any original contribution to science or even supported his contributions with strong evidence as a scientist. It is a very harsh statement, but many scientist share this view.

Sociobiology has many followers, but also many detractors, like the geneticist R. Lewontin.

Indeed, Lewontin and Gould have been my greater detractors. But you should take into account that both of them were Marxists. They were also very honest, open-minded people, but their opposition —they recognised— was political.

Do you think that maybe some of his disciples’ ideas were too sensationalistic? I am thinking about Richard Dawkins’ works ( The Blind Watchmaker, The selfish gene… )

I suppose that some books on sociobiology are indeed sensationalistic. Some of its authors have only gone into speculation with the only purpose of provoking. But most of what has been published is top-quality work, specially in Dawkins’ case… I think Dawkins has been controversial for his strong defense of atheism, for writing against religion in the latest years… But his works on sociobiology are very good.

© T. Poschmam

Do you think that in order to be a good science communicator one has to be first of all an specialist?

Yes, I do believe that. It is obvious that we have excellent authors who write on scientific issues and are basically journalists. I know this from my own experience as a science communicator. But if someone wants to be original and master the topic one is dealing with, then, one has to have a scientific career behind, or at least some scientific education.

Your book The diversity of life strongly calls for biodiversity, and so does your book The future of life. Do you think people is still unaware of the situation of biodiversity, that the problem is the lack of communication?

I think so. I think that a great deal of the problem lays on the fact that biodiversity is something hard to understand compared to other environmental problems. People easily understands what pollution is, global warming or the ozone hole, but they don’t get what the extinction of species or ecosystems means for them. The average American, and most certainly many Europeans as well, have read about the extinction of a great deal of species, especially in tropical forests or in coral reefs, but they don’t see the connection between that and their lives.

So, do you actually believe that people will be able to save biodiversity, according to what you say in The future of life?

Yes, I think so. I am very optimistic…But, every time I start to feel a little bit more optimistic some country or another, including my own, does something so stupid that my faith in the possibility of finding a rational solution to the problems the protection of nature poses weakens.

© T. Poschmam

The editor of New York Times‘ science section once said that one of the obstacles science communication has to face is that scientists like to speculate and to focus on areas of their research that are not very clear yet, while readers prefer facts. What other obstacles make the communication between scientists and the public difficult?

I think the public wants both things. The public wants the facts, but they also want adventure. Scientists live on adventure. Good scientists are explorers and adventurers, and the silver and gold of science are its new findings. One becomes a successful scientist when he or she makes an original finding. The quest for new phenomena is what keeps the best scientists on the edge of knowledge. And that is why the best scientists speculate. But this is not vain speculation. At least it isn’t if it truly stimulates new ways of thinking, new experiments and other forms of exploration to determine what is true and what is not. I understand that people think that scientists spend their life conjecturing.

Scientific knowledge has doubled every fifty years since the mid 17th century. That is why we have so many scientists and technicians. This is mainly an achievement of the Western civilisations. Scientists don’t like spending much of their time talking about what is already known, because that doesn’t fall within the category of «new discoveries». But I think the general public is interested in everything —in what they already know, but also in new findings.

«I actually believe that people will be able to save biodiversity. I am very optimistic»

And don’t you think scientists like very much to talk in a somehow cryptic way?

No, I don’t. Let me explain: bad scientists like to use a cryptic language. Good scientists prefer to speak plainly and make themselves understood. I think it was Lord Rutherford —a great physicist who developed his work a century ago— who said that everything you can’t explain to your barman in ten minutes is probably not worth explaining. Likewise, when scientists talk among themselves they have to be precise. And common English, common Catalan or any other language has not enough vocabulary that enables them to express themselves in a precise way. It is the like going to the doctor and having a prescription written —one needs accuracy.

Likewise, a good scientific article has to have both elements: a technical part to explain methodology and results, but also an introduction as well as discussion. And there is where knowledge diffusion begins.

So, in order to be a good science communicator one has to be a good scientist first.

Of course. To be a good communicator one has to be skilled with language as well. And many scientists, I must admit, are not very good writers.

Do you think that a scientist is morally obliged to diffuse his or her work?

Not in all areas, but they are in many of them.

«We can learn absolutely nothing from ants from a moral point of view —they are the most aggressive beings on Earth»

Such as?

Well, those that affect people. For instance, if a scientist studies the blood chemistry of South American reptiles, he or she may not feel the obligation of sharing with the general public his or her findings. His or her findings can certainly be very important for a better understanding of the evolution of reptile physiology, but it may not be as important as sharing new findings in biomedicine or ecosystem stability. Although it is also important for astronomers and physicists to share what is out there, the cosmos, because people are fascinated by the universe. We have excellent scientific writers, like Hawkins, who do a very good job.

I have heard that people frequently ask you what can we learn from ants, and that you systematically say that “absolutely nothing”. How come? Weren’t ants those insects that would work for the whole summer so that winter wouldn’t catch them off-guard…

From a moral, or social, point of view, better not to learn anything from ants. Ants are, mainly, very harmonious inside their colonies. However, colonies are always fighting one against the other. They are the most aggressive being on Earth, including human beings. If ants had weapons of mass destruction, the world would be over in a week.