What would you think if I was your co-worker and I told you that there was a fire in the building, yet you saw me continue with my work as if nothing happened? You would probably think that I was trying to play a joke on you (not even a particularly funny one), or that I needed a couple more coffees because I was not fully awake. And I am also sure that, the next time I cried fire, you would not trust me. You would not think it important, because surely – you would think – it is just another unfounded alert.

With the sudden shift from climate change to climate emergency in media terminology, but also in the communication of many institutions, experts tried to take a further step forward in communicating what global warming means. To decorate it with the appropriate time scale. Given our very slow and unambitious reaction, new strategies had to be tried, and words matter. For example, global warming has more emotional appeal than climate change, according to various studies. Now, despite the fact that the intention was good and born from a critical reflection of the world of environmental journalism and communication, the incorporation of the word emergency generates two complex problems to solve.

«No government has taken any dramatic measures against climate change after the emergency was declared»

The first is purely communicative. The process that causes this emergency is and will always be a change in the climate. The climate emergency has a human, civilizing dimension, resulting from the very rapid rise in temperatures. But they are not synonymous, and there is a risk, as already happened when change was popularised instead of warming, that certain sectors will consider it to be merely a marketing strategy, an attempt to hide scientific inconsistencies. We must stimulate social awareness, but we cannot ignore scientific dissemination.

The second is more serious, and has to do with the example I gave at the beginning. We declare an emergency in countries, regions and cities: okay. Perfect. What now? No government has taken any dramatic measures against climate change after the emergency was declared. What is the point, then? Why did they do it? The banalisation of the climate emergency will mean, like Aesop’s fable, that no one will pay attention the next time we cry «The wolf is coming!». An institutional declaration is useless, and the lack of action transmits that, deep down, the climate emergency is just a pose. It is important for us to take a picture, to look good, to get on the wave of sensitivity for the environment, but acting is, alas, complicated: it calls for sacrifices, it forces us to compromise and also to make enemies. But an emergency either builds a new framework that makes disruptive actions possible in record time or it is not an emergency.

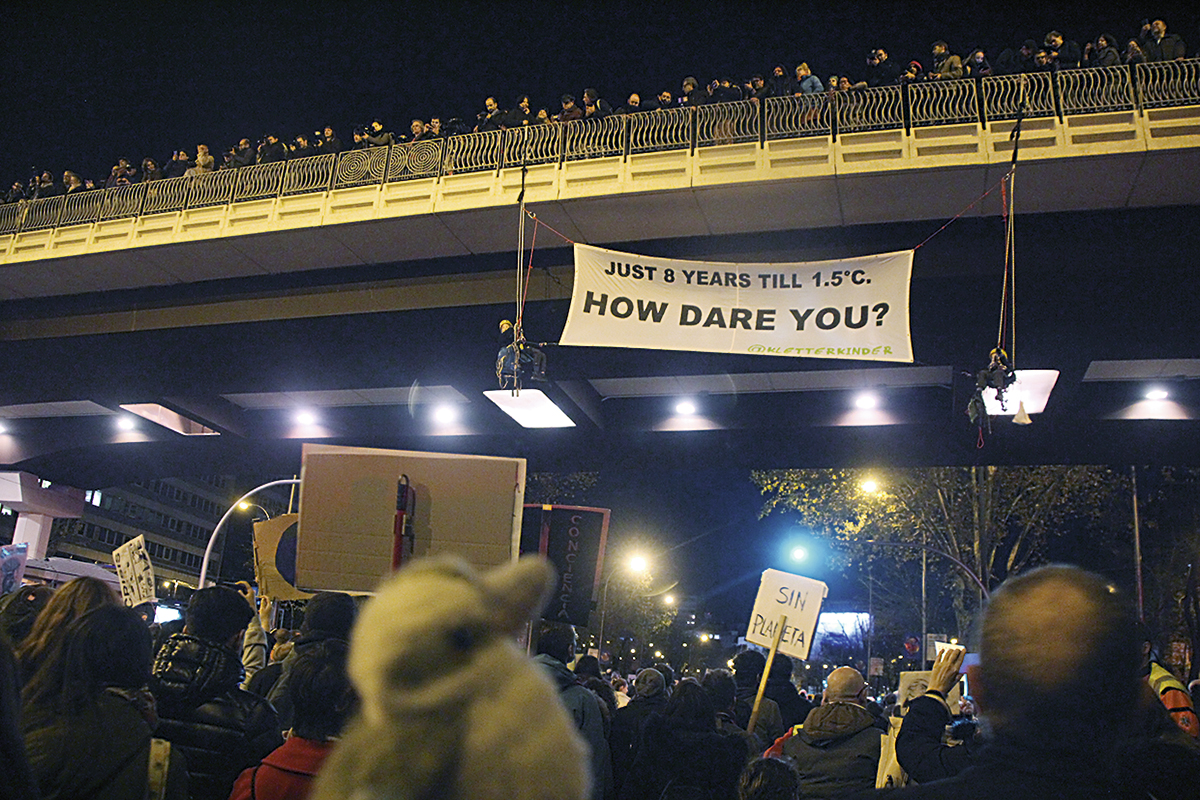

The dissonance between what we say and what we do was most evident at COP25 in Madrid. At the summit, after a whole year of mobilisations for climate, an ambitious agreement was expected, even though the calendar pointed to the Glasgow summit in 2020 as the moment when the rules of the Paris agreement would be defined. But… can we really wait a whole year if we are in an emergency? If month after month we break temperature records, and every report that is published on climate change shows that it is a present, real, and constantly accelerating process… can we afford fourteen days of unproductive talk (sponsored, of course, by Big Energy)? It seems obvious that we cannot.

We have barely a decade to push for a 50% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, and less than 30 years to reduce them to net zero. We are indeed in an emergency. Let there be no doubt about that. But if there is one thing that is even more paralysing than not accepting the situation we are in, it is saying that our house is on fire and then calmly keep watching television.