It is all there in the drawing of the wind

The dialectic between nature and technology in the films by Hayao Miyazaki

Before founding the legendary Studio Ghibli alongside Isao Takahata (1935–2018) in 1980, Hayao Miyazaki (1941) worked for several Japanese animation companies, including Toei Animation and Nippon Animation. At the latter, in 1978, he created the series Future boy Conan (Mirai Shōnen Konan). The opening credits are still astonishing today. They show bombers taking off over a modern megalopolis, triggering a war that wipes out society and life on the planet. The apocalyptic premise repeated in Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (Kaze no Tani no Naushika, 1981), the first film to be produced by Studio Ghibli. Conan and Nausicaä are both set after the catastrophe. In the former, only one generation after the war, we follow a series of survivors at odds over how to live in the future. More specifically, there is the Industria model, where they want to continue using technology and rationally organising society, and the High Harbor model, a community dedicated to agriculture, livestock farming, and craftsmanship. In Nausicaä, on the other hand, many centuries have passed since the war, but we also find humanity divided into different factions, one of which wants to dominate the rest by developing the old industrial technology. However, what stands out in this film is how nature has regenerated in the form of a large forest protected by giant insects that release toxins. These toxins seem to be an antibody against the destructive action of humankind.

Inhabiting the world

It is not hard to imagine that Miyazaki’s fixation on disaster is related to Japan’s contemporary history, marked by the country’s role in World War II and, above all, by the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Moreover, Conan and Nausicaä are products of the Cold War, when the threat of a nuclear holocaust was very real. In addition, Japan, apart from being the only country to have been the victim of nuclear weapons, has developed a powerful nuclear industry, despite the fact that it is a volcanic archipelago that is prone to major earthquakes. In any case, Miyazaki’s great concern is humanity’s destructive potential. There are many more examples of this in his filmography: Laputa, the floating Castle in the sky (Tenkuu no shiro Laputa, 1985), has an unimaginable power of destruction; the horror of the Great War (1914–1919) traumatised the protagonist of Porco Rosso (Kurenai no Buta, 1992); and in Howl’s moving castle (Hauru no ugoku shiro, 2004), one of Howl’s nocturnal journeys brings him to a place ravaged by a terrible conflict.

Miyazaki’s fixation on war disasters is linked to Japan’s contemporary history, marked by the country’s role in World War II. In the image, a still from the opening credits of Future boy Conan shows a modern megalopolis being bombed.

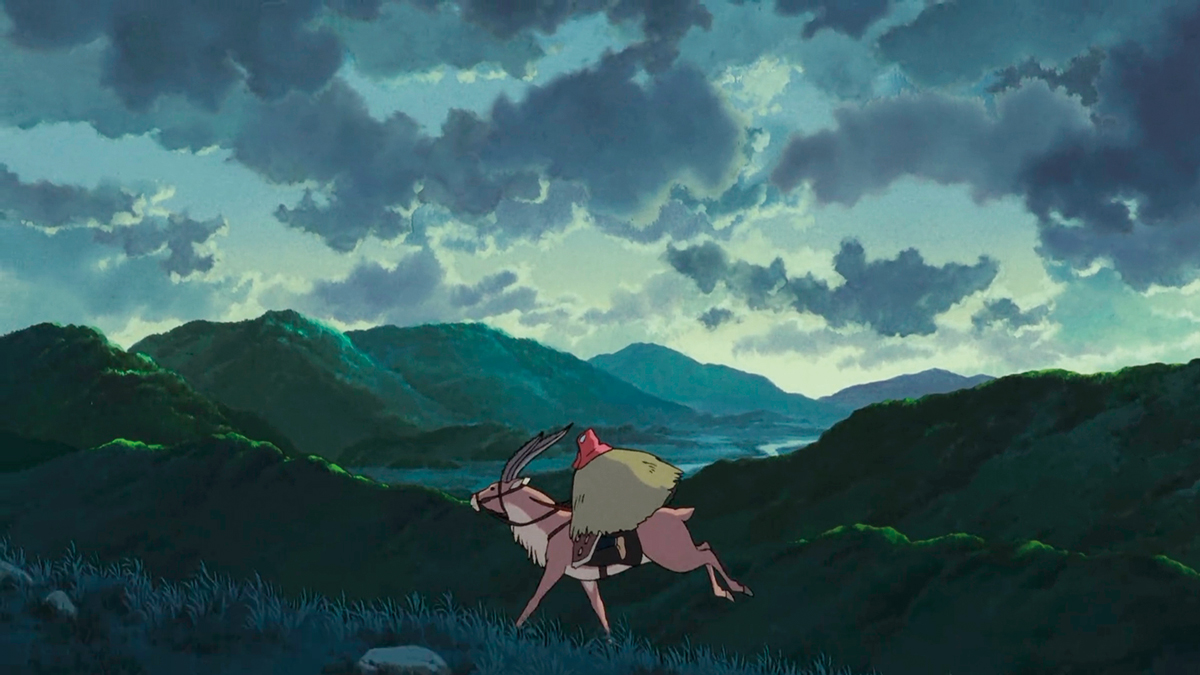

Among these references, however, Princess Mononoke (Mononoke Hime, 1997) stands out. In the film, we witness a confrontation between animals, who represent nature, and an army of humans who want to impose themselves in order to consolidate industry and progress. From this point of view, it is a fundamental film for understanding Miyazaki’s thinking, not so much for its approach as for the problems that arise from it. From the very beginning, Miyazaki presents the conflict in a dialectical way: the confrontation between those who want to live in harmony with nature and those who want to develop human life independently. It is worth mentioning that Princess Mononoke is set in the Muromachi period (1336–1573), a time when Japan underwent significant technical progress and a change of mentality that provoked a crisis in Shinto animist thinking, which conceives of nature as a supernatural entity, governed by spirits called Kami, Yokai, or Yurei. However, Miyazaki’s way of thinking may be dialectical, but it is by no means overly simplistic, i.e., this is not a story of good guys and bad guys. Even in the early Conan, which does present a clear confrontation between two antagonistic positions (the heroic Conan versus the fanatical Lepka), what is most interesting is the dramatic evolution of other characters, especially certain secondary characters who manage to change their minds (Dyce and Monsley). This is emphasised even more in Nausicaä and Princess Mononoke, both of which are choral films with many groups of people, each with their own legitimate reasons.

«Miyazaki’s great concern is humanity’s destructive potential»

Moreover, although his ecological discourse is laudable, which is the ideal, it does not hide the contradictions inherent in the dialectical process itself, which have much to do with the human condition. The films talk, no less, about the difficulties that human beings encounter when living in nature, caused by our own fragility, and how we can only deal with them using our intellect, that is to say, using technology. And our intellect, in turn, allows us to understand life and death, which are always present in Miyazaki’s work. That is why it is very difficult to identify ourselves with San, the uncompromising human leading the animal side in a war against her own kind. Eboshi, on the other hand, is a fascinating character we are eager to learn more about. She is the ambitious leader who founded a city where a fledgling industry is developing. She welcomes the marginalised and dignifies them by teaching them to work (in a context, lest we forget, of great social violence). And, above all, she is prepared to do anything to protect them, even killing the forest gods if necessary. For all these reasons, Miyazaki does not hesitate to show that resolving the conflict is very difficult, hence the need for the help of an external agent who acts as a mediator, which allows him to transcend the conflict, essentially because he is not conditioned by the «blindfold of hatred».

In Miyazaki’s films, nature is presented as magnificent and sublime. This is contrasted with the human capacity for destruction, which is at the heart of one of his most famous films, Princess Mononoke.

Despite the synthetic nature of the solution in Nausicaä or Princess Mononoke, Miyazaki’s approach is most interesting in its realism: condemning technology is a contradiction, yet we understand that it can cause an ever-widening rift between humankind and nature. And even though we know for certain that this is the beginning of all disasters to come. This reasoning starts out as a confrontation between nature and technology, but, as we have already seen, it mutates into a confrontation between tradition and modernity. The key moment in Japan’s history in this sense is what is known as the Meiji Revolution (1860), which was not only the most intense social reform in the country’s history, but also signified an opening up to the West after centuries of deliberate isolation. It is worth remembering that when the Portuguese and Spanish began to travel and colonise the world from the 16th century onwards, the Japanese greeted them with an unstable mixture of fascination and abhorrence. Europeans were so strange to them that they might as well have been voyagers from another planet. In the end, however, the feeling of aversion prevailed, basically against the Christian religion. But everything changed three centuries later, when Westerners, driven by the power and technology of the first industrial revolution, went on another colonising offensive. This was a commercial and military colonisation, not just a religious one, and the Japanese statesmen saw no alternative for survival but to adopt Western technology. To this end, students were sent to universities in Europe and the United States to learn and copy everything they needed for the change.

The collective imagination of this period, which spanned the second half of the 19th century and the early 20th century, was a source of inspiration for Miyazaki. To illustrate this, films such as Castle in the sky, Howl’s moving castle, and Porco Rosso are set directly in European landscapes of the period. And, most importantly, they show a particular fixation with machines, from new means of transport to new weapons. Of course, this group of films includes The wind rises (Kaze tachinu, 2013), his film testament, where we explicitly find the keys to understanding many elements of his filmography. Without going any further, the film is a tribute to the pioneering engineers of aeronautics, a field that has always fascinated Miyazaki. Moreover, The wind rises is an important film, because it is a historical reenactment of Japan’s modernisation process; we see the chimneys of the new factories, the population leaving the rural areas and flooding into the cities, and a progressive change in people’s mentality and customs, as evidenced by the fact that we see citizens who are already dressed in Western clothes, while others still walk around in kimonos and other Japanese garments. Indeed, Miyazaki is well aware of the challenges posed by the transition to a modern society. The Japanese statesmen tried to restrict Western influence only to technical knowledge, but they did not succeed. Technology operates on the surface of life; at first glance, it seems like a plausible option that needs not affect the whole set of customs. But it soon became clear that all aspects of society were intimately connected, and one can certainly come to think of this modernisation process as a sort of mechanical Trojan horse. The most obvious result of Japan’s great industrialisation was the suffering of the working classes and the disaster of World War II, after years of nationalist and imperialist drift, aspects of which The wind rises also echoes.

Again, this question forces us to think about the particular Miyazakian discourse, because the protagonist is an engineer who only wants to design and build aeroplanes, and even travels to Germany to perfect his technique. His passion is genuine and totally altruistic, even though he knows that his inventions will be used as an instrument of death. However, Miyazaki’s stance can in no way be considered naïve, because he knows that human beings cannot give up their capacity for innovation and, above all, their creative genius. This is the clear and courageous humanism that makes the film so heartbreaking and inspiring at the same time. It should also be noted that The Wind Rises is a powerful depiction of the Great Kanto Earthquake (1921), a natural disaster that once again underscores the tension between nature and humans, and how humans can only defend themselves through intellect and technology. Not surprisingly, the film is also an ode to work and effort, which must go hand in hand with inspiration to make us better. In short, it is a difficult situation to resolve, which is why in his most realistic film Miyazaki avoids, unlike in previous works, any conciliatory message in favour of a responsible use of technology. Instead, he has no qualms about showing a negative view of Japanese technocrats, and at the same time, during the German section of the film, showing the climate of horror brought about by the Nazis. This commitment was already familiar in Porco Rosso, where he also valued the combination of work and inspiration, and whose protagonist says an unforgettable sentence when he is celebrated by the powers that be: «I’d rather be a pig than a fascist».

The other worlds

Despite being about the history of Japan, The wind rises is notable for its incorporation of European cultural elements. Paul Valéry’s poetry, repeated throughout the film, the musical and literary references to German culture, the pictorial elements of French Impressionism, and the character of the Italian engineer are evidence of Japan’s cultural fascination with the West, of which Miyazaki is a clear heir. In fact, as we have already seen, what stands out in some of his films is the coexistence of Eastern and Western features, in what could be classified as a cultural collage. It is a playful practice based on a deeper thought: there are many worlds. Indeed, Miyazaki’s importance in cinema lies in how he teaches us to move from one world to another.

In his theory and practice, different approaches can be identified. The first is an undisguised fascination with the magical and the wondrous. Miyazaki builds possible worlds where different cultures are mixed and where fantasy is also a key element. To illustrate this, his historical European settings contain traits that could be considered steampunk. They develop in retro-futuristic settings in which steam and Victorian technology is mixed with fantasy flying or nautical devices. The trick is how quickly the viewer gets used to them. Miyazaki also makes the seemingly impossible easy, as with the door in Howl’s moving castle that is used to move from one dimension to another, the grace with which the protagonist of the film ages or rejuvenates depending on his mood, or the naturality with which Porco Rosso acquires the features of an animal and continues to live in the world of humans as if nothing had happened. This is a commitment to creativity made possible, above all, by the freedom of the artist in front of the blank page, which Miyazaki exercises with a boundless imagination. But, at the same time, it is much more than that. The animated figures, be they realistic, fantastic, or even objects coming to life (like Calcifer, the fire genie in Howl’s moving castle), must be creative sources of expression, capable of conveying a feeling or an affection.

«In his films, Miyazaki notes that the boundless confidence in progress and growth inherent in modern thinking and state dynamics leads directly to catastrophe»

In the same line, we must also consider the resources of dreams and legends. On the one hand, the role of oneirism in his most realistic film, The wind rises, stands out, as it serves to visualise in a very beautiful way the workings of inspiration and, at the same time, the links with a tradition that connects us to our origins and helps us to reach originality from tradition. It is an idea conveyed through a sequence of images that create an alternative reality to portray an immaterial value: creativity connected to tradition, a splendid counterpoint to the harsh reality of modernisation, which only aspires to continued progress and to sever links with the past. It is therefore essential to take into account the memory of those who have gone before us, which we can integrate through narratives to give them the value they deserve. This is precisely the purpose of the legend Porco Rosso tells about his experience in the war, in which he draws a picture of a community of fallen airmen who inhabit another world and who find redemption and reconciliation in their afterlife.

Miyazaki’s oeuvre also includes works with an exclusively Japanese theme and setting, but marked by the same desire to expand the limits of reality. Shintoism and Buddhism, the two traditional religions of Japan, play an important role here. From the outset, some of the keys that we have seen in Miyazaki’s poetics are clearly inspired by these religions; not surprisingly, Shinto animism calls for an integration with nature and Buddhism teaches that the relationship between human beings and nature is not one of opposition, but of reciprocal dependence, not to mention that Miyazaki is also interested in the Buddha’s pacifism. Apart from Princess Mononoke and The wind rises, two other films stand out for their exclusively Japanese setting are My neighbor Totoro (Tonari no Totoro, 1988) and Spirited away (Sen to Chihiro no kamikakushi, 2001). The former is set in the post-war period and is a delightful journey into rural Japanese life, when pre-modernisation ways and traditions had not yet been supplanted by Western customs. On the other hand, Spirited away shows the journey of a girl from present-day urban Japan to a fantasy reality in which different aspects of Japanese cultural tradition are blended. In both films, religious references are explicit, as seen in the various Shinto shrines and temples dedicated to the divinity Inari, which show the characters’ respect for nature, as Inari provides with food through land and cultivation. Miyazaki also uses various ghosts, spirits, and supernatural creatures that are part of Shinto mythology. What stands out is how these references are used to move from one reality, the modern and rational one, to a different one, more traditional and fantastic. These journeys are also conceived as a rite of passage, not only bringing the protagonists into contact with other realities, but also serving as a way for them to mature.

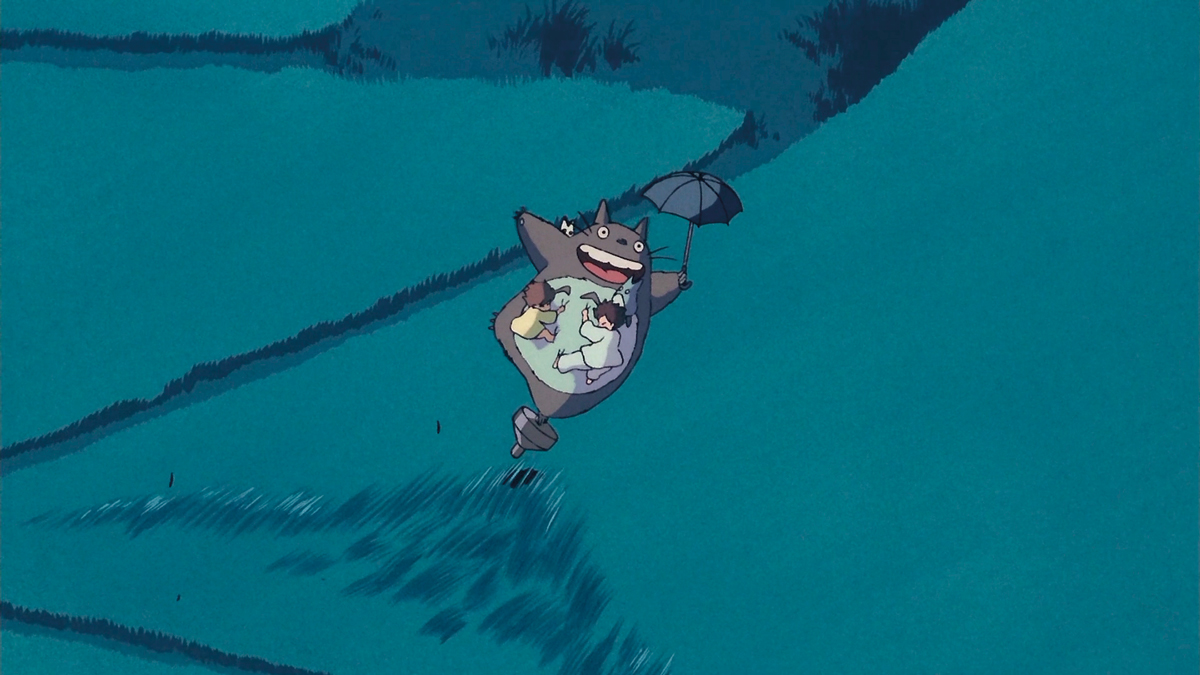

Miyazaki’s poetics blend ideas from Shinto and Buddhist folklore, based on respect for nature for providing us with food from the land and cultivation, and the idea that all beings are equally important in the workings of the universe. Films aimed at younger audiences, such as My neighbor Totoro, are representative of these ideas.

Finally, this poetics of the plurality of worlds brings us to a level that is, actually, the first of all: childhood. In many of Miyazaki’s films, the children are the ones who encounter a marvellous creature and run to their parents, who do not pay much attention because they consider it an illusion arising from the senses and the imagination of the little ones. The best example of this is Ponyo (Gake no ue no Ponyo, 2008), starring children and, above all, designed for them. Miyazaki works with the idea that in children’s experience the boundaries between the physical and psychic worlds, between the material world and the spiritual world, are blurred. And the beauty of it is that he manages to present this integration without making it look like an adult perspective. This approach is, in fact, extremely difficult, because it is necessary to show the essence of an extraordinarily complex world very clearly. Not surprisingly, Ponyo uses Japanese mythology, Greek mythology and Hans Christian Andersen’s tale of The little mermaid to reproduce the essence of a child’s thinking. Indeed, Miyazaki depicts the sea as a mother figure, as the origin of life, a myth found in many cultures around the world. However, this is not just cultural syncretism, but rather a child’s capacity to wonder at the world, to learn, to intuit somehow the complexity and anguish of our world. This is basically why a film aimed at children is so enjoyable for adults too, not only because we can remember who we once were, but because we understand that childhood provides very important experiences for everyone. These experiences are the key to the fundamental problems of life: the meaning of things, what is good, justice, etc.

In Miyazaki’s films, drawing the wind becomes the perfect metaphor for the forces that transcend material boundaries and move the world, but are invisible to the naked eye. In the images, the protagonists of Spirited away (above) and My neighbor Totoro (below) are carried by the wind on their great adventure.

Conclusion

Hayao Miyazaki’s films have something else in common. Those pictures of nature, both in the skies of Castle in the sky and in the forests of Princess Mononoke, present it as grandiose and make human figures insignificant living something that is close to anguish. Of course, there is also the importance of the sea, so present in Conan or Ponyo. It represents a danger to human life, as well as a mysterious fascination, essentially because it is both a source of latent violence and the space where life emerged. In any case, it is related to sublimation, an aspect that is very present in Miyazaki’s innovative action scenes. Miyazaki conceives chases as efforts to overcome human physical limits, be it through pirouettes in the sky piloting fabulous machines or in races on land or water. Finally, there is an effort to reproduce the wind as a force of nature, in one of his major stylistic features. For example, in My neighbour Totoro, the wind carries people from one world to another, while in Spirited away, the wind seems to push the girl into the tunnel that will mark the beginning of the adventure. There is also the wind of history, fundamental to understanding the historical film The wind rises or the desolation of his post-apocalyptic works. This is why it is all there in the drawing of the wind, which becomes the perfect metaphor to represent forces that go beyond material limits and move the world, invisible to the naked eye.

Through his exciting filmography, Miyazaki has certainly developed his vision as an auteur, but he has also been able to abstract himself from the contingencies of life to catch a glimpse of a space where the values with which we usually measure life – coming from scientific modernity – are just not enough. Miyazaki is greatly fascinated by technology, but at the same time he misses thinking about the sacred aspects of the world. In all his films, he seems to be telling us that something more is necessary, some sort of transcendence. This quandary came from the West, which is perhaps why Miyazaki’s films are so moving to us in this part of the world, because he is able to create a lost space for humans not as individuals, but as part of a community, of humanity, and of the entirety of the cosmos.