When it comes to disasters, catastrophes, and apocalypses, it is not easy to take us by surprise. In the course of our lives, each of us has been given an intensive course in the assimilation of potential scenarios in the form of fictional stories: from children’s fairy tales to fantasy films, the diversity of scenarios rehearsed in our minds is enormous. Of all the evils that can befall us, as far as reason and the laws of physics allow, every one, or practically every one, has been written somewhere. Meteorites, world wars, volcanic eruptions, popular revolts, environmental catastrophes, pandemics… Agustín Fernández Mallo put it very well in his book Teoría general de la basura (“General garbage theory”): fictions do their job “[…] so that, when disaster strikes, when the cataclysm comes, our unconscious, thanks to paranoia, already has a rehearsed constant, a plank to hold on to in order to withstand the transition to a new environment […]”.

Human beings have been telling stories for as long as we have been able to do so, ever since language equipped us with the ability to mentally exchange ideas. This function of storytelling, preparing our minds for what is to come, has a fascinating parallel with the greatest of our fantasies: the dreams that creep into our sleeping minds every night. They are a daily treatment before we wake up, warming up the engine to gradually unwind our nervous system so that, when the moment comes to return to reality, we are not taken by surprise. Or at least this is one of the hypotheses put forward about the function – or one of the functions – of dreams.

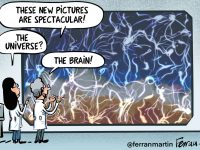

Neuroscience is still far from clear on why we need to sleep, although there are several hypotheses that may explain the function – or functions – of the different phases of sleep. Essentially, throughout the night, periods of deep sleep – or slow-wave sleep – alternate with moments of sleep in which our eyes move in a distinctive way, as if we were watching some internal fiction (REM sleep, for rapid eye movement). Deep sleep and REM sleep alternate throughout the night, but their timing changes. The REM phase, in which most dreaming occurs, increases in duration as the night progresses, so that as we approach dawn, we also spend more time dreaming. Some researchers believe that this crescendo facilitates a quick and efficient transition from sleep to wakefulness. According to this, dreams, the hallucinatory and implausible journeys that we experience every night – even when we do not remember them – play a role similar to that of cinema and literature in our societies: they prepare us for tomorrow; but not because of the content of the story, which is inconsequential in dreams, but because they simply trigger neuronal activity.

Newborns spend more time in REM sleep than adults, and it spreads over their entire daily sleep cycle. In this case, it would not be a preparation for awakening, but rather a training process that would facilitate the development and consolidation of neural architecture.

In adult life, fantasies are indispensable, they are part of our human nature, we need them as a society to face the surprises along the way and, as individuals, they allow us to face each day with well-oiled neuronal circuits. The dream of reason produces monsters, yes; monsters we eat up as a preventive treatment against what the future may bring.