We are (and will always be) ephemeral

Stories about futures with improved humans

Stories about the future, and about the humans living in the future, stem from our awareness of our own limitations and all that which we may never be. These representations, whether utopian or dystopian, are evidence of the contradiction between our desires and our doubts.

Keywords: science fiction, mythology, superheroes, pop culture, dystopia.

Let us pick two very specific moments in which beings reinterpreted and sublimated in fiction were faced with evidence of their own fragility. One of them is the fateful moment when the warrior Achilles saw Paris’s arrow pierce his heel – his only weak point – according to the legend started by the poet Statius. The other one is issue 61 of Superman’s adventures, when the hero realises that kryptonite, a mineral from his home planet, could dim his powers and make him as vulnerable as any other human being (Siegel & Schuster, 1949). These moments were separated by several centuries; in fact, the former became the canon in the light of which the latter was created but nonetheless, both share the same essence. The discourse surrounding the concept of posthumans, or the vision of a world in which we are better and more advanced and have managed to challenge our expiry dates, always stems from our realisation of our own fragility. We are aware of our ephemeral condition, and fiction creates heroes and antiheroes to embody the eternal battle for eternity.

Since the beginning of time, we have imagined realities in which we transcend our limitations and overcome old weaknesses, but nonetheless they still end up being an inseparable part of our stories. This is because, in the end, we cannot conceive a future (or the humans who will live in it) without assuming that all these narratives are a parable for our awareness of that which we may never be able to become. The representation of any future, be it utopian or dystopian, captures the present and with it, our desire or hope to become a different thing. It is a reflection of our drive for survival in a world that condemns us to disappear, or maybe of our fear of being absorbed by the machine or by the misuse of technological advances. The novel 1984 (Orwell, 1949/ 2010) is one of the most influential examples of this. Most of these stories talk about what we would like to be as a metaphor for what we really are, and they often start from a contradiction: their protagonists are our salvation while also being the ultimate expression of our doubts, as well as our lights and shadows. That is the reason why the idea of a future with improved humans involves an in-depth study of the persistence of pain, resignation, and sacrifice as the driving forces behind the transformation. Countless authors and titles fall into this group, which can be subdivided following three axes to understand their relevance along the history of popular culture: mythology, evolution, and technology.

Of myths and humans

In narratives about the future, the fear of being absorbed by the machine or the misuse of technological advances are often present. George Orwell’s novel 1984 is one of the most influential examples. / Anaconda verlag

It is not at all outlandish to state that much of modern Western fiction can be articulated mainly from three distinct legacies: biblical texts, Greek mythology, and Arthurian legends. The former were expressed as stories of redemption, of assumption of the punishments of existence and the Stations of the Cross that the characters must face to overcome their heavy consciences and unconfessed sins; the second group chronicles common individuals who are actually destined to reign and the glory of great feats that would have otherwise been out of their reach; and the third group manifests worlds populated by hyperbolic heroes who represent our collective aspiration for eternity.

They all share many features, two of which are quite obvious: the fight against time (i.e., our ephemeral and finite condition) and our desire to be recognised by a higher entity that can sanction the meaning of our journey. They also share a common search for moral or emotional refuge, a compass to guide us towards our destiny and our own selves. Mass culture is full of these sorts of representations of never ending searches in which most characters are the children of what Umberto Eco called the ideology of consolation (Eco, 1964). In other words, heroes who comfort us because they are not the superhumans they would like to be.

The legacy of mythology is palpable in both classical literature and the production of audiovisual fiction throughout the 20th century (Arnaudo, 2013; Reynolds, 1992; Unceta Gómez, 2007). The collection of divinities of Greek mythology and the long list of heroes looking for their approval have adopted countless faces and have now become the pop culture mould for a new way of narrating. Superheroes are the clearest and most valid manifestation of this model. They were born in comic strip form as an antidote to the social and political crises of the last century and turned into a synthesis of our concept of modernity thanks to their TV and cinema translations. Superheroes embody our projection of an improved humanity and are sometimes even the result of the evolution of divine figures (either our own or those of others). Thus, comics, films, and TV series deal with the search for divinity in human beings and, above all, the search for humanity in divine beings. They exceed our limits, but they are a simultaneous reminder that we do have those limitations.

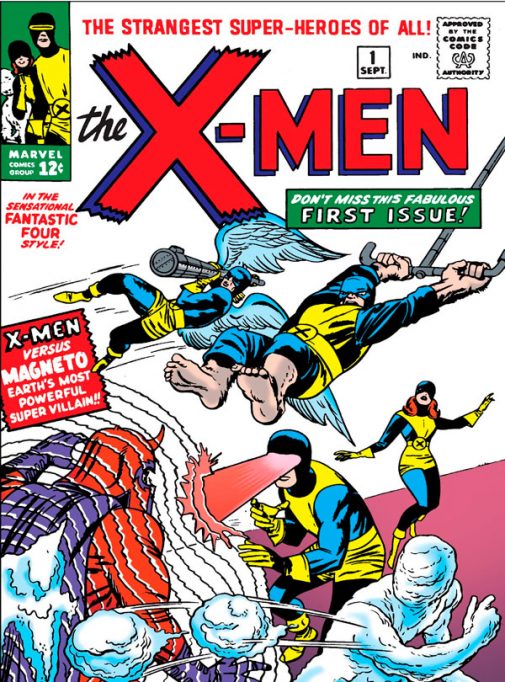

The X-Men are feared by their compatriots, who are intimidated by their superhuman powers. This thematic interest comes from a transversal canon which applies to all genre fiction: fear of the different. / Marvel Comics

An approximation to some of these characters might provide some eloquent insight into this argument. Superman, one of the most iconic superheroes of all time, moves between messianism and being a traditional superhuman. His transition through our daily lives chronicles the tension of being aware that he is exceptional and knowing that the realisation of such exceptionality is unequivocally human. One needs only to look at the paradigm of how the mythological superman hides his true identity in the guise of an unrefined, insecure, and socially dysfunctional journalist. Similarly, Captain America, a symbol of the fight against absolute evil as personified in Nazism, was a weak, sickly, and futureless young man who, thanks to a serum, became a super soldier in one of the best and most evident depictions of improved humanity. Strictly in reference to films, M. Night Shyamalan proposed another example in the trilogy that started with Unbreakable: the idea that the improvement of humanity has already occurred and that superhumans already live among us. However, in this director’s universe, we are not yet ready to accept these heroes (nor are they, deep down, ready to accept themselves) because we refuse to transcend what we understand as normality. In this sense, we must also mention the premise of the comic book Watchmen and its cinematic and television counterparts (especially the latter, as a true distillation of its essence) which describe a reality in which superhumans are perceived as subversive and are threatening to trigger an apocalypse. Another example is The boys (both the comic book and the TV series) in which the superhero paints a vivid picture of double standards and the progressive degradation of our values.

It is no coincidence that representations of superhumans in popular culture, once established as a genre, repeatedly torpedo their foundations and increasingly reflect upon the configuration of these narratives. After all, we live in an era in which we have become more aware than ever of the fragility of something we took for granted and which superheroes embody – ultimately, the collective idea of a better world that is far from becoming real. Thus, our collective certainty that we are all living in a dystopia from which we should have been saved has forever changed audiovisual formulations.

The dangers of evolution

Evolution is one of the most common recurring formulas in fiction and is used as a means to discuss the future of humans – either naturally or by breaking some imaginary «life ceiling» as the result of genetic manipulation. The main exponents of the first category came from the X-Men comic books (Lee & Kirby, 1963) as well as their cinema and TV adaptations. These stories were born as a reverberation of the 1960s social struggles in the United States and as a metaphor for generalised intolerance (issue number one was published in 1963 and was quite clear on its intent); the mutant characters depicted are feared by their compatriots, who are intimidated by their superhuman powers. This thematic interest comes from a transversal canon which applies to all genre fiction: fear of the different. We have always imagined what would happen if our species made an evolutionary leap, and these fictional channels are mostly used to warn of the consequences of such a leap. Again, imagining a near future is used to discus the present—the here and now. Therefore, despite being born during a specific and particularly agitated historical period, the X-Men still stands as the perfect representation of the political conflicts of any given time.

Another key aspect in the portrait of the evolution of modern fiction is the one emerging from the novel Brave new world, by Aldous Huxley: a utopian society based on the superiority of exceptional individuals. The improvement of the species based on genetic selection is a plot device that has led to the emergence of an entire era of fantasy stories. One of the best audiovisual versions of the book, although not an official adaptation, is Gattaca, by Andrew Niccol. Released in 1997, in the midst of debate on the applications of genetic engineering, the film wonders what would happen in the future if births occurred according to artificial selection criteria that allowed societies to be led by exceptional individuals. The main characters are two brothers, one of which was born with assistance and a future full of opportunities, while the other was the result of a natural birth and suffers from a heart condition that limits his chances of achieving a lifespan exceeding 30 years. Ultimately, it was the perfect synthesis of evolution debates. On the one hand, we want to believe that future generations will correct and improve our own, but we also have doubts regarding the extent to which we can manipulate the natural order of things.

Captain America, a symbol of the fight against absolute evil as personified in Nazism, was a weak, sickly, and futureless young man who, thanks to a serum, became a super soldier in one of the best and most evident depictions of improved humanity. In the image, stills from the film Captain America: The first avenger (2011), directed by Joe Johnston in 2011, showing the moment of his transformation. / Marvel Studios / Paramount Pictures

Challenging nature and its consequences is another inherent aspect of projections of our future. In this sense, we cannot avoid referring to the mythology of Frankenstein in its many forms. What if, in the attempt to create life where there is none, we create a being that mirrors the monster within us? Many modern formulations have tried to answer this question, from warnings such as Splice by Vincenzo Natali (in which a group of scientists create a hybrid being that learns to manipulate their emotions and instincts), to influential video games like Hitman, about a genetic experiment that inhibits the development of feelings in newborn babies in order to turn them into relentless killers.

Regarding cloning – another recurring theme in relation with evolution – we must mention the TV series Orphan black, about a young woman who discovers she was the subject of an experiment that had created numerous copies of herself. In addition, the classic The boys from Brazil, a thriller by Franklin J. Schaffner based on Ira Levin’s novel about a scientist who wants to clone Adolf Hitler, follows similar themes.

The fear of monsters – most importantly, the monster within – is one of the driving forces behind the genre. To analyse its importance, it is paramount to also consider the novel The island of Doctor Moreau, by H. G. Wells. This book explores how the drive to replicate and evolve humans degenerates into the creation of a genetic nightmare, framing a discussion of the dangers of tyranny.

Another key work about mutations and their different readings is The fly, by David Cronenberg, a version of a short story by George Langelaan that had already been adapted by Kurt Neumann in 1958. Cronenberg relates the story of a researcher who invents a teleportation machine but ends up merging with a fly during one of the tests. The film focuses on his metamorphosis, which the scientist initially perceives as an opportunity to improve the human species. Indeed, before his horrible realisation of what it really meant for his humanity, one of the consequences of the transformation was the belief that the skills obtained from the insect had made him superhuman albeit doomed to be feared and misunderstood. The fly was released over three decades ago, but it is still one of the best cinema representations of the dangers of believing that we can accelerate our evolution. According to a monographic essay by Jorge Gorostiza and Ana Pérez (2003), as a director, Cronenberg has delved deeper into the symbolism of meat as a means to map human transformations than anyone else.

Virtual eternity

There is an old idea that progress is associated with the achievement of immortality. According to these fictions, humans will be able to extend their time in the world thanks to different technological advancements that will correct the conditions that make us vulnerable and, in the long run, finite. Authors including Frank Herbert (The eyes of Heisenberg), Isaac Asimov (in his Foundation series), or Michael Crichton (The terminal man) have explored a future based on the dialectic between man and machine. Stories about the loss of humanity implied by the existence of machines predominate in genre fiction, as do others about machines gaining self-awareness and demanding their place in the world. In this sense, iconic films such as Terminator or Blade runner are good examples (Sala, 2017). But there is also a third option in the form of technical advances that can turn humans into superhumans, always presented with a warning – once again – about the dangers of trying to reshape nature’s moulds. In these stories, characters revive, survive, or improve thanks to machines, but along the way, they compromise their societal role and end up having to reconsider who they really are. One of the films that explores this topic best is Robocop, by Paul Verhoeven. Policeman Alex Murphy is reconstructed and brought back to life with the help of robotics, but the memories and emotions of his time as a human create conflicts with the character’s software guidelines. Indeed, this is a very current duality, given that modern society is often in a constant struggle between who we are and who we pretend to be through virtual devices.

Fiction shows us technical advances that can turn humans into superhumans, always presented with a warning – once again – about the dangers of trying to reshape nature. In Paul Verhoeven’s film Robocop (1987), the policeman Alex Murphy is reconstructed and brought back to life with the help of robotics, but the memories and emotions of his time as a human create conflicts with the character’s software guidelines. / Orion Pictures

Similarly, in Upgrade, by Leigh Whannell, we see a man who can walk again thanks to technology but who uses the titular improvements to carry out an act of revenge with somewhat biblical connotations. The debate here focuses on the legitimacy of taking advantage of technology to satisfy our primary instincts. Touching on a different sort of extreme (and extreme is the right world, because the film is absolutely radical), the Japanese film Tetsuo: The iron man, by Shinya Tsukamoto, introduces us to a protagonist who dreams of a metal and wire world that will enable a collective mutation within a technological delusion.

Just like humans, machines have also undergone an evolution in films. Contemporary fantasy cinema has turned parables about elementary geared machines into great dissertations on the invasion of virtuality into our lives. The most seminal film of this type of our time is The Matrix, by the Wachowski sisters, in which society is enslaved within a computer programme until a few heroes (quite powerfully named Neo, Morpheus, and Trinity) rebel to recover human dominion. Few modern films have combined such diverse languages so well to imagine the role of superhumans in a hypothetical future: Neo must learn to separate reality from appearance, to shape himself as a character (with a priceless scene in which he learns martial arts because he is able to reprogramme himself to do so), and finally assume his role as the new messiah in a war between the virtual and tangible worlds. Another essential title to understand future humans is the TV series Black mirror, an anthology about how technological applications can affect the way we live, relate, or even die. Among many other things, it proposes the idea of a virtual eternity in which a body is completely unnecessary, as well as video games that allow us to assume our avatar’s identity in order to act out our most repressed dreams.

Awareness of the ends

In any case, however advanced the machine is, however sophisticated our virtual worlds become, however powerful the superhuman, and no matter how evolved we manage to become as individuals, all these stories discuss the same topics and reach the same conclusions. Each human is destined to meet their end; and up until that moment, we are also destined to suffer because being aware of our ephemeral nature is what gives us true meaning. This is very clearly addressed at the end of Blade runner, when Roy Batty, aware of his imminent expiration, validates what he has seen and experienced as the essence of immortality. We will advance, we will progress and improve; we will challenge (and maybe even fool) time, but we will never defeat it. Modern fiction (fantasy or otherwise) emanates from this realisation, because we dress our future «selves» in all our present grief and impossibilities.

References

Arnaudo, M. (2013). The myth of the superhero. The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Eco, U. (1964). Apocalípticos e integrados. Debolsillo.

Gorostiza, J., & Pérez, A. (2003). David Cronenberg. Cátedra.

Lee, S., & Kirby, J. (1963). The X-Men #1. Marvel.

Mayor, A. (2018). Gods and robots: Myths, machines, and ancient dreams of technology. Princenton University Press. Retrieved from https://press.princeton.edu/books/hardcover/9780691183510/gods-and-robots

Orwell, G. (2010). 1984. Edicions 62. (Original published in 1949).

Reynolds, R. (1992). Super heroes: A modern mythology. University Press of Mississippi.

Sala, A. (2017). Just imagine. 50 títulos esenciales del cine de ciencia ficción. Editorial UOC.

Siegel, J., & Schuster, J. (1949). Superman Vol 1 #61. IDW Publishing.

Unceta Gómez, L. (2007). Mito clásico y cultura popular: Reminiscencias mitológicas en el cómic estadounidense. EPOS, XXIII, 333–344. https://doi.org/10.5944/epos.23.2007.10559