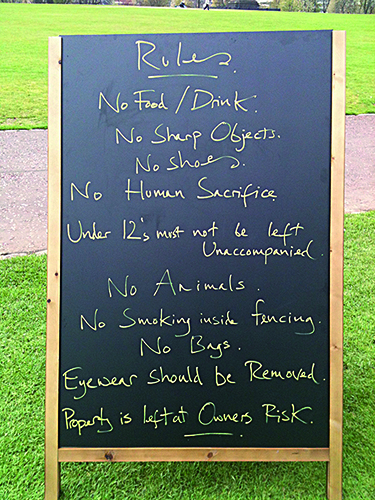

Jeremy Deller. Sacrilege, 2012. Mobile installation. / Tom Ledger.

Anthropology, history and, to a lesser degree, sociology have shown continued interest in festivals and rituals in general, and those marking the various stages of life in particular. Festivities, although exceptional in that they can be seen as the opposite of everyday life, provide an opportunity to understand a society and its culture that daily life does not provide, except over a long period of time. To some extent, festivals reveal a society, its structures and values, real or symbolic, in a short space of time and in a specific and manageable geographical area. At a festival, all the members of a social unit externalise their roles, renew their status, display their most treasured beliefs, symbols and icons and bring contradictions to light. Social classes are displayed and identities reaffirmed, and all this in a recreational, ceremonial, artistic and colourful atmosphere, flavoured with food and drink that stir up emotions, which sometimes reach catharsis. For all these reasons, the study of festivals is appealing to those studying social sciences.

«People’s lives go through a series of stages: from birth through childhood, youth, maturity and old age, inexorably leading to death. Man has culturized the passage through these stages»

There are festivals that involve society as a whole, and others that directly affect only sections of society, albeit indirectly, by presence or absence, involving the whole group. One should not forget the eminently local nature of most festivals. Ignorance of this fact may lead to numerous misunderstandings, with visitors thinking that the festival is held for their benefit and enjoyment, and that the celebration should serve their interests. This is apparent in certain festivals, which have gone beyond the local and regional levels and become a tourist attraction, leading to certain contradictions we will not go into. Here, by contrast, we will refer only to those celebrations held to mark the transition from one stage of life to another in different age groups, in other words, that accompany the rites of passage of which they form an integral part. The celebrations cited in this article, though occasionally valid for Spain as a whole, are typical of Andalucía –where the study took place– and chronologically cover the period spanning the last third of the twentieth century to the present.

The life cycle and rites of passage

Jeremy Deller. Sacrilege, 2012. Mobile installation. / Felibrilu.

People’s lives go through a series of stages: from birth through childhood, youth, maturity and old age, inexorably leading to death. Man has culturized the passage through these stages, adapting them to environmental circumstances and life expectancy, marking them with festive rituals that establish a turning point, a before and after, and a change of status. These are called rites of passage, according to Van Gennep’s terminology, rituals that occur in festive contexts. Each society has its own established rituals, which they have adapted to their own culture, giving prominence to those they consider more valuable socially. For example, so-called primitive societies attached great importance to puberty, at which point children were no longer children, but became mature youths and thus eligible to reproduce and create social units, giving continuity to society and fulfilling the ultimate goal of any social unit. By contrast, Western society has downplayed and even hidden or denied this rite of passage because, traditionally, this change was not valued as it was not considered useful, or was hidden, ignoring these necessary functions until a later stage in young people’s lives. Anyhow, nowadays these festive rituals related to age groups have been reduced and simplified.

«These steps are established according to gender and age group, so that all male or female members of a community pass them at the same stage in life»

These steps are established according to gender and age group, so that all male or female members of a community pass them at the same stage in life, although not always simultaneously, for instance in smaller units like the family unit. Among the same age group, affinities are created and solidarity born of coexistence and mutual experiences lived, which the rituals embody and distinguish. In traditional Spanish society, the main steps are endorsed by the Catholic Church and civil laws, which condition and govern them, bestowing upon them a mystic character in the former case, while legally sanctioning them in the latter.

Christening or baptism by the Catholic Church is the first major festival linked to the life cycle. The picture shows an infant under the protection of the Virgin (Andalucía). / Photo: Salvador Rodríguez Becerra

An ad hoc classification could be as follows. First, christening or baptism, which is the recognition of the newborn as a Christian, on the one hand, and as a member of society on the other, and requiring registration in the baptismal and civil registers, and allocation of a proper name. Second is the first communion, which marks the end of childhood and the recognition of having reached the «age of reason» or ability to discern right from wrong and assume certain responsibility for the one’s acts. Puberty, as remarked above, is not marked by ritual in Western societies, and runs uneventfully until adulthood, which also goes unmarked nowadays. Until recently adulthood was marked by entering the military service, at the age of between eighteen and twenty, although this was only the case for young men. Until a few decades ago, the festival, known as entrada en quintas in Spanish (becoming a conscript), marked the end of youth and beginning of early adulthood, with civil responsibility and readiness for entering into marriage. This moment in life was also marked for women, in that, through marriage and wedding celebrations, a new stage was set for both genders.

Then began a long period of varying length for men and women, depending on life expectancy, which included rights and obligations up until old age, but which did not involve any rituals in traditional –basically rural– society. However, in recent decades, celebrations organised by co-workers, tend to mark the age of retirement, which usually implies the right to a pension. Death, which, although not unique to any particular age group, is more prevalent in the elderly, and is marked by an elaborate and sometimes complex ritual, which involves mourning, funeral, and burial, the latter in a Catholic or municipal cemetery. This event, fraught with great emotional burden, was very common in traditional societies until very recently, it was a complex ritual lasting months or even years, observed by the family, and especially by women, who were fully or partially marginalised by society and excluded from social activities and entertainment for years, as they were obliged to mourn, as a permanent reminder of the deceased.

Festivals and rites of passage

The first communion has turned into a sort of «mini-wedding», evident in the attire worn by children, especially girls, as shown in the picture. This ritual marks the end of early childhood. / Photo: Salvador Rodríguez Becerra

In traditional society, the birth of a new family member and his/her christening, was generally a joyful event, but sometimes met with resignation and even pain, and was celebrated with a small festival of very limited scope and duration. The birth of a child was the result of married life and this was not always well received, although either joy or resignation was expressed with a phrase coined to refer to the unborn child: «he’s on his way». Nobody could claim that traditional society was pro-abortionist, except in rare cases of extreme neediness, and the arrival of the newborn was celebrated during the christening, which marked his/her full integration into society. Until the baptism, which took place within the first forty days of life, neither mother nor child went out of the house, and the father fetched the godfather, previously chosen during pregnancy or on accepting the offer of a friend. In either case, the godfather agreed to «pour water over the baby» and bear the expenses that the celebration this entailed. The godmother was either the wife of the godfather, or any other member of his family. In Andalucía, during the epoch referred to in this article, it was not common for godparents to cross the boundaries of social class, but rather godparents were generally chosen from among family and friends.

After the ceremony in the parish church, a small procession –often just the godparents, the father and a neighbour– would go to the house and along the way youngsters asked the godfather for pennies or candies, singing a song once and again along the path: «padrino, no te los gastes en vino, tíralo al pelón» (godfather, don’t spend it on wine, toss it to «baldy», referring to the newborn). Back at the house, the godmother would hand the baby to its mother saying, «Comadre, aquí tiene a su hijo. Me lo entregó moro y se lo devuelvo cristiano» (Co-mother, here is your son. You gave him to me a heathen, and I return him a Christian). They would invite the family and some other neighbours, but the celebration did not last long, as the christening used to be held in the early evening, and it would also depend on how ostentatious the godfather was. Nonetheless, there was no shortage wine, spirits, cakes and other sweets. If the sucking child, as infants were called, did not survive –given the high infant mortality rate well into the second half of the twentieth century– they were buried without any fuss. The christening marked the beginning of a special relationship between godparents and godchild, and between parents and godparents, in which each was mutually obliged to the other and, among other things, required them to show respect for one another.

Despite profound changes in moral and family traditions, marriage is still an essential rite of passage in our modern societies, marking the start of adulthood and in many cases the onset of the reproductive period. The photograph shows a wedding in Xàtiva in 1900. / Col·lecció Díaz Prosper. University of Valencia

The next stage was the first communion, which used to be taken by children between seven and nine years old. It was believed that at this age children had already attained «the use of reason» and could distinguish right from wrong, and therefore could and should be punished when they transgressed the rules. In general, with the exception of families of a certain social standing, this ritual was not accompanied by the celebration of a festival, apart from a brunch given to the children taking communion that day, provided by the school or parish in many cases. In recent decades, however, the festival organised by parents on occasion of the first communion has changed considerably, to the point where it has turned into a «mini-wedding». It resembles this in terms of the attire worn by the children, with boys sporting a military uniform or something similar, and particularly the girls, who wear real bridal gowns. Moreover, the size of the celebration has grown, and can be considered a true banquet in most cases. Strangely, although the children are the centre of the celebration, the adults take the main part, as it is the parents who invite family and friends, and decide on the menu according to their economic status. Children often receive gifts nowadays, while previously relatives would visit to give them money. By contrast, when the confirmation is held, this sacrament is of little relevance to the majority of society, and it does not involve a festive celebration of any kind.

A festival that is no longer held, but which signalled an important change in a man’s life in the past, revolved around the figure of the young man, brought out into the town square to be called up for military service. Conscription, though not mandatory for everyone –as some were excused for various reasons or avoided it through subterfuge–, was compulsory for most young men. They belonged to a conscript known as a quinta, relating to the year of their birth, and formed a compact group of young men who entered a kind of «time out» and were thus afforded certain license and relieved of some obligations. Various celebrations were held, where the families provided the means for the group of conscripts to enjoy themselves. These festivals were highly carnival-like, and therefore transgressed the established order with mocking criticism aimed at individuals and families, via songs and graffiti. In some places these young men undertook acts of sexual initiation in city brothels. After their military service their manhood was accepted, and they were expected to fulfil the duties demanded of young men: responsibility, marriage and starting a family, but they also began to enjoy privileges, for example, they were allowed to frequent bars and smoke in their father’s presence.

«Marriage was the most momentous rite of passage for men, but more so for women. Achieving motherhood was an intimate achievement»

Other celebrations that mark the end of childhood and early youth are popular bullfights or capeas, highly popular in the mountain regions of Andalucía, and more recently participation in the Easter procession, helping to carry the float with the saint or throne. For women, there are no rituals marking their passage from youth to womanhood, only if they had a boyfriend they should be demure and not be seen out. In recent times, the celebration of separately held stag and hen parties has become widespread, where the bounds of modesty are transgressed by gestures, verbal expressions and erotic objects.

Involvement in the festival can mark the transition from childhood to adulthood, such as the bull on a rope in Grazalema, Cádiz (2007). / Photo: Salvador Rodríguez Becerra

Marriage was the most momentous rite of passage for men, but especially for women. Marriage allowed free access to sexuality –forbidden until that moment– with the man of her desire, which was to set new limits and simultaneously free her from her family’s tutelage, However, sometimes she would be liberated from the former only to enter into another relationship of dependency, on her husband. Attaining motherhood was an intimate achievement. In any case, the new house, were it possible, was the woman’s stronghold, where she was mistress of the space and its contents. This momentous change in young people’s lives was ritualised in the wedding festival, in which the couple took part after a rather long period of courtship, and in accordance with land ownership and inheritance laws, they were united in a church ceremony –the only form considered acceptable– forever or «until death do us part». There were no acceptable ways of breaking off a marriage, and few couples lived physically apart, thus the formal status was retained even though the man had occasional or even permanent extramarital relationships. A wedding signified a commitment between the couple’s families, formalised with the exchange of possessions by both parties for the future married couple. And after the religious ceremony, a meal was always held, which would last all day and to which almost the whole community was invited in the case of a village wedding. Guests were expected to hand over sums of money proportional to the degree of kinship, proximity to the families and economic standing. The honeymoon was nonexistent, and if it did happen would involve a short stay with a family member or in a nearby city. In the second half of the last century, the practice known as «llevarse a la novia» (stealing the bride) was still done, which was nothing more than a way to avoid family pressure, obligations and wedding expenses. In practice the couple acted by mutual agreement and, after escaping, held a religious ceremony in private and at unusual hours. By the end of the last century, civil ceremonies in municipal registry offices had become widespread, and the number of guests attending banquets has increased. In many other cases, couples live together without any ritual to celebrate the fact.

Family with a dead child (J. Rodriguez, ca. 1900). Today’s denial of death is in contrast with the way our ancestors dealt with it. / Col·lecció Díaz Prosper.

Although death is apparently contrary to festivity, this is only on the surface. Death traditionally had a festive and almost humorous component, especially apparent in the wake. When death struck in small communities, at least one representative from each family was required to attend and accompany the deceased and his/her family for some time, especially through the night. In the deceased person’s house the corpse was properly shrouded, which for the majority meant a suit, and laid out in a room or some other place with a number of seats set around, even in hallways or at the front door. In some towns, neighbours brought bars of chocolate to provide comfort during the night’s vigil, others brought broth or other types of food and beverage, which in no way amounted to a banquet or feast. But it was not so much the intake of food and drink, but rather the conversations and chitchat, often ending in contained laughter, naturally at some distance from the family and their deceased member. When someone especially witty or humorous entered the scene and started telling anecdotes about the deceased, the tone would rise with nervous laughter. These scenes are almost extinct now, due to the denial of death, practiced by contemporary society, which disposes of the dead as quickly, neatly and discreetly as possible with the help of funeral homes and crematories.

In conclusion, all societies mark the stages in the life cycle –from birth to death– of its members with rites, ceremonies, and entertaining events like festivals, which serve among other things to highlight them as different from the normal day to day. They also indicate that certain members of the community have a new status thereafter, giving them certain rights and implying new obligations. The importance each society attaches to these festivals, or even the absence thereof, is indicative of their value system.

References

Flores Arroyuelo, F., 2006. Las edades de la vida. Ritos y tradiciones populares en España. Alianza. Madrid.

Molina, P. and F. Checa (eds.), 1997. La función simbólica de los ritos. Icaria. Barcelona.

Rodríguez Becerra, S., 1981. «Noviazgo y ritual de boda en Gistaín (Huesca). Anotaciones etnográficas». I Congreso de Aragón de Etnología y Antropología. Diputación Provincial. Zaragoza.

Rodríguez Becerra, S., 1997. «Rituales de muerte en Andalucía. Significados y funciones». In Molina, P. and F. Checa, (eds.). La función simbólica de los ritos. Icaria. Barcelona.

Segalen, M., 2005. Ritos y rituales contemporáneos. Alianza. Madrid.

Van Gennep, A., 2008. Los ritos de paso. Alianza. Madrid.