ABSTRACT

A scientific career is often like an obstacle course, but for women there are additional problems and specific mechanisms of exclusion. This article shows us the strategies used to overcome some such hurdles by reviewing the biographies of four psychologists who endeavoured to receive academic training, between 1890 and 1940, and managed to make a personal contribution to psychological science.

Keywords: psychologists, history, Mary W. Calkins, Anna Freud, Beatrice Edgell, Mercedes Rodrigo.

«In the nineteenth century there were barriers that almost totally prevented women from becoming registered students. It was not until the 1970s that women enjoyed conditions of parity regarding opportunities and status»

Women scientists who opted for an academic career have generally had to overcome at least three obstacles (Valentine, 2005; Russo and O’Connell, 1980). Firstly, the cultural barriers, which taught them that studying at university was not what society expected of them. Secondly, once they did gain entry to university lecture halls, they found themselves subject to suspicion. In this sense, they found themselves up against the challenge of dispelling the widespread belief that women were incapable of intensive and quality intellectual labour. Finally, once they had achieved this goal, often after considerable effort, they still had to face discriminatory structural hurdles when seeking employment opportunities. In particular, those women who decided to marry found it even more difficult to access a prestigious university position, which would enable them to perform research and teaching or to publish.

«Neither her director’s praise, nor endorsement by the board of examiners, were able to sway the university, which refused to grant Calkins the title of Doctor because she was a woman»

Considering these hurdles, it is not surprising that only a few women took up scientific careers. Therefore, these pioneers’ careers are noteworthy. In general, in the nineteenth century there were barriers that almost totally prevented women from becoming registered students. During the first half of the twentieth century a few of them managed (Bohan, 1992), but it was not until the seventies that women enjoyed conditions of parity regarding opportunities and status (with particular reference to the second generation of American psychologists, see Johnston and Johnson, 2008).

Below, I will go on to discuss the trajectories of some pioneers in the field of psychology, a relatively young discipline that started to become established in the second half of the nineteenth century. During the first decades, psychology was still institutionally fragile, historically characterised by an obsession for methodology in order to defend its scientific status on a par with other natural sciences, such as physics or chemistry.

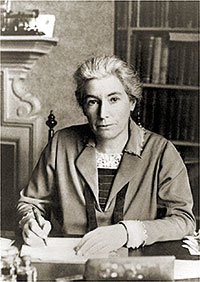

CALKINS: DOCTOR WITHOUT A TITLE

The first woman who stands out as a pioneer in the field of psychology is the American Mary Whiton Calkins (1863-1930). Calkins was the eldest of five children, and maintained close ties with her family throughout her lifetime. Her parents encouraged and helped her to obtain a solid university education through the first university colleges for women in the United States. Throughout her career she was able to study philosophy and specialise in experimental psychology (Furumoto, 1980).

Faced with the dilemma of having to choose between a career and a family, Mary Calkins decided to remain single and put her energy into contributing to science. Thus she became a PhD candidate under the direction of Hugo Münsterberg at Harvard University. In 1895 she successfully defended her PhD thesis on the learning of associated words (paired-associate learning). Her supervisor was impressed by her work capacity and her brilliant mind and he declared to the academic authorities that Calkins was the best PhD candidate he had ever had and would probably become the best expert in psychology in the country. But neither her director’s praise, nor subsequent endorsement by the board of examiners, were able to sway the university, which refused to grant her the title of Doctor due to the fact she was a woman.

After getting her PhD. in Germany, Beatrice Edgell established a psychological laboratory in a women’s college and in 1927 she became the first woman in England to become a Professor of Psychology.

When, years later, Münsterberg managed to get the title granted through another university (Radcliffe), Calkins thanked him but declined the offer. If she had met the formal requirements for a PhD degree from Harvard, why should she settle for a title from Radcliffe? She spent her life fighting against gender discrimination in education, saying it was akin to prescribing a different diet to men and women: «Do you think it would be proper to prescribe a diet of candy for women and meat for men? Just like the body, the human mind also needs a bit of everything to grow and develop». Calkins was a bold woman, who denounced what she believed to be unfair at a time when most people accepted the norms differentiating men and women’s social roles.

Mary Calkins worked as a professor at Wellesley College for the remainder of her life, where she set up one of the first psychological laboratories (Wilson, 2003), an institution where women could receive experimental training. In addition to teaching, she published a great many works (four books and around a hundred articles) in which she developed her own theory, known as «psychology as science of self», which was totally opposed to the behavioural psychology in vogue at the time.

Although she never received her official Harvard PhD title and her work was limited within the bounds of a small women’s college, throughout her career she achieved national and international recognition for her scientific contribution. Finally, in 1905, she was named President of the American Psychological Association(APA).

Mary Whiton Calkins started one of the first psychology laboratories and developed the so called theory of «psychology as a science of self», which totally opposed the most respected one at the time– behaviourism. On the right, Calkins with some American colleagues at Cambridge (Masachussets) in 1919. / Archives of the History of American Psychology

EDGELL: THE FOREIGN PHD CANDIDATE

One woman who did receive the title of Doctor of Psychology was the British psychologist Beatrice Edgell (1871-1948). Again, as in the case of Calkins, she received her family’s support to study and decided not to marry. Although ten years Calkins’ junior, she also had difficulty in finding a university that would admit women. Luckily, Edgell was finally accepted at Aberystwyth College in Wales where, albeit separately, both women and men could attend the college. In 1894 she graduated in mental and moral science (Valentine, 2005).

«In 1901, Beatrice Edgell was to become the first woman to graduate from the University of Würzburg and the first English woman with a doctorate in psychology»

However, to pursue her career and PhD. studies was not easy, so Edgell decided to go to Germany to study a postgraduate at the University of Würzburg. She was unable to register officially but was allowed to attend the lectures of the psychologist Oswald Külpe. Then, in 1901 she successfully completed her work and on her doctoral dissertation viva voce became the first woman to graduate from the University of Würzburg and, at the same time, the first British woman to hold a doctorate in psychology.

Anna Freud had a direct confrontation with the psychoanalyst Melanie Klein. This confrontation only ended when both of their studies were officially recognised as being academically valid. / Sigmund Freud Museum, Viena

Edgell was very lucky because, in fact, women were not accepted in university lecture halls in Germany, requiring special permits to be granted by the regional ministry. But it would seem that foreign women were admitted more easily as they would return to their own countries afterwards, while German women would likely want to continue their careers at local universities. Furthermore, the secondary education Edgell received in England provided a more comprehensive grounding than that usually imparted in Germany.

On returning to England with her prestigious doctoral degree from a German university, Edgell was able to set up a psychological laboratory at a women’s college, Bedford College. The project began with scarce resources but with help from the heads of the physiology laboratories, and with patience and perseverance, she managed to build a productive laboratory carrying out psychological research. In 1927 she was appointed Professor of Psychology, being the first woman to hold this title in Britain. Her work at the university was highly productive, becoming a mentor and publishing books and articles. One of her best-known books is an introductory course in psychology, which takes into account emotional attitudes and the application of psychological knowledge to real-life situations (Valentine, 2005).

ANNA FREUD: IN HER FATHER’S SHADOW

One of the women pioneers in the field of psychoanalysis was Anna Freud (1895-1982), the youngest daughter of the famous psychiatrist Sigmund Freud. Anna began her studies in Vienna, where she worked as a primary school teacher between 1915 and 1920. At the time she received psychoanalytic training and preparation under her father’s guidance. In 1922, she formally entered the professional circle as a new member of the Vienna Psychoanalytic Association.

Described as a woman of great energy, she managed her father’s businesses and responsibilities when he began to suffer health problems due to mouth cancer. Given her experience as a teacher, it was not long before Anna Freud began to combine her interest in psychoanalytic methods with educational matters. Indeed, with the publication of her work on child psychoanalysis in 1927, she became Vienna’s most renowned analyst in this field.

«Described as a woman of great energy, Anna Freud managed her father’s businesses and responsibilities when he began to suffer health problems due to cancer»

Around the same time, a conflict arose between her position and that of the psychoanalyst Melanie Klein. Anna postulated a later onset of the superego in children, strongly influenced by environmental stimulation. Klein did not distinguish between child and adult mental dynamics and psychoanalysed young children at play; however, Anna Freud maintained a clear distinction and stated that language abilities were a prerequisite for analysis to be carried out (Volkmann and Lück, 2002).

«Anna Freud combined her interests in psychoanalysis and pedagogy. With the publication of her work on child psychoanalysis in 1927, she became Vienna’s most renowned analyst in this field»

This clash of ideas was aggravated when the Freud family was forced into exile, having to leave Vienna and go to London due to the Nazi invasion of Austria in 1938. After her father’s death, Anna Freud took over and defended his legacy. She spent several years immersed in the pain of war and ongoing academic confrontation with the group that supported Klein’s thesis. During those years she mostly worked with abandoned and traumatised children. Together with her friend Dorothy Burlingham, she set up the first nursery school and later a clinic in Hampstead to care for children and their families, as well as training psychoanalysts.

After the Second World War, peace also returned to the psychoanalysts’ world in London, with the official approval and recognition of both specialisations (Klein’s and Anna’s). Throughout her life she received several awards for her scientific work, including the title of Doctor Honoris Causa by Clark University (USA).

RODRIGO: WARTIME DIRECTOR

Another psychologist belonging to the same generation as Anna Freud was Mercedes Rodrigo Bellido (1891-1982), who trained as a teacher in Madrid. Interested in the new discipline known as psycho-pedagogy, she visited various institutions both inside and outside Spain just before the First World War broke out. After the war, she left Spain once more, to work with Édouard Claparède at the Jean-Jacques Rousseau Institute in Geneva. In 1923 she returned to Spain as an expert in special education, with a degree in psychology, and started to work in teacher training.

«In general, Women psycologists moved between two extremes: a challenging attitude of protest to one of submissive complicity»

When the occupational centre –Instituto para la Reeducación Profesional de Inválidos del Trabajo– was set up, Mercedes took charge of the career guidance unit, and became a pioneer in psycho-techniques, in the field of applied psychology, developing quantitative psycho-technical tests. Consequently, shortly afterwards Jose Germain was to ask for her collaboration at the National Psycho-technical Institute (Instituto Nacional de Psicotecnia), set up in 1928. From her teaching post at the Institute, she trained and mentored a generation of psychologists in Spain. In 1931, while continuing her previous job in parallel, she also started to work as child psychologist for the Child Protection Court (Tribunal Tutelar de Menores), which led her to promote children’s mental health and wellbeing.

When the Spanish Civil War broke out, the director decided to go abroad and left her in charge of the institution throughout the war. Rodrigo devoted most of her time to organising the evacuation of children from Madrid, a city under siege and the constant target of bombing. While others were fleeing, she stayed on to run rehabilitation institutions for young offenders. Once the war was over, while those who had left could return to the country, Mercedes Rodrigo was forced into exile, even though –according to Herrero (2003a and 2003b) – she had never actively supported any political party. At first she went to Bogota (Colombia), where she stayed for eleven years working to set up the first university student selection programmes. The growing demand for psycho-technical testing services led to the establishment of the Institute of Applied Psychology at Colombia’s National University, in 1947, which was directed by Rodrigo. Thanks to her work training psychologists, she is now considered the pioneer of scientific psychology in Colombia, as well as a pioneer in the field of psycho-technical testing in numerous countries in South America.

Despite her success, after a conservative government came to power in 1948, she fell victim to accusations of being a communist, a label that Spanish exiles often received during this time. Thus, in 1950 (at the age of 59) she faced a second exile, this time in Puerto Rico where she again resumed her work with enthusiasm and energy. In Puerto Rico, Rodrigo worked as a university professor of education, because there were no schools of psychology. Then after 1955, she provided psychotherapy services for U.S. veterans at Julià de San Juan’s private clinic (Guil Bozal and Vera Gil, 2011).

Her professional reputation reached a summit in 1958 when she was appointed president of the Puerto Rico Psychological Association. Before she died, she was to receive homage from the society of psychologists in Colombia, being awarded the first prize by the Colombia Federation of Psychology in 1971.

FINAL COMMENT: WOMEN AND PSYCHOLOGY

Over a century ago, women were already drawn towards the study of psychology, beginning to run courses and doctoral degrees specialising in this field. Once trained as psychologists, they also wanted to form part of the scientific community and its component scientific societies.

One of the first was the American Psychological Association (APA), which was founded in 1892. Contrary to what happened in other scientific societies such as physiology, the APA admitted women members almost since the moment of its foundation. In fact, in 1917 the female sector comprised 13% of membership, a higher proportion than in any other American scientific society. Likewise, the number of women qualified in psychology is noteworthy: in 1921 the proportion of women holding a PhD in psychology was higher than in any other scientific field (Valentine, 2005; Scarborough, 1994).

This does not mean that there were no obstacles for women to overcome in the field of psychology, but rather there were a number of brave women, like those mentioned here, that received the support they needed to follow this career. It is a context in which García Dauder (2010) discusses the mechanisms of exclusion and resistance. Many of these women scientists came from middle class families with a high cultural level. They typically received support from their mother or father, who wanted a high-level education for their daughter, even though it was unusual at that time.

The strategies adopted to overcome the obstacles mentioned at the beginning are of great importance. First, it is noteworthy that none of the women discussed here got married. They were ambitious women, who on being faced with the «family versus career» dilemma clearly considered marriage to be incompatible with a scientific career. As some historians have shown, when women married or had children their academic careers were hampered or, often, abandoned altogether.

They moved between two extremes: a challenging attitude of protest to one of submissive complicity. Psychologists like Calkins dared to clearly demarcate the boundaries up to which they were willing to abide by the rules of the academic game, exemplified when she rejected the second-class PhD title, offered as consolation. As Valentine (2005) remarks, Edgell adopted an intermediate so-called «Madame Curie» strategy, based on quiet but deliberate over-qualification, personal modesty, a great deal of self-discipline and stoicism. Another factor that undoubtedly helped was an ability to create social support networks, both at the professional and private level.

Mercedes Rodrigo followed a similar path, devoted above all to developing an innovative professional career after receiving prestigious international training abroad. She knew how to look for male allies and dared to take on the responsibility and burden of running the National Psycho-technical Institute when her country was gripped by years of crisis and war.

Anna Freud’s case was somewhat different, as her career was tied to her father’s reputation and ideas; notwithstanding, she soon developed her own field of expertise. When her father’s health worsened, she inherited his legacy and dominant position within the group of psychoanalysts in Vienna.

As in the case of the Spanish psychologist, political events disrupted her career. However, once abroad, both Anna Freud and Mercedes Rodrigo resumed their work activities, albeit with great difficulty. These difficulties were not the result of sex discrimination but rather of exile, exacerbated by a theory-related conflict, in the former case, and political indictment in the second.

The psychologists discussed here specialised in diverse areas, with Edgell specialising in experimental psychology; Calkins in more philosophical issues; Mercedes Rodrigo in psycho-pedagogy and psycho-technical testing; and, Anna Freud in child psychoanalysis. These women’s areas of expertise were not generally considered of high scientific standing among the dominant academic psychology of the time (United States), which was more empirical and based mainly on the observation and control of behaviour. However, at some time in their lives, they were all to receive recognition by professional societies of psychology.

References

Bohan, J., 1992. Re-placing Women in Psychology: Readings Toward a More Inclusive History. Kendall. United States.

Furumoto, L., 1980. «Mary Whiton Calkins (1863-1930)». Psychology of Women Quarterly, 5: 55-68. DOI: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.1981.tb01033.x

García Dauder, S., 2010. «El olvido de las mujeres pioneras en la Historia de la Psicología», Revista de Historia de la Psicología, 31(4): 9-22.

Guil Bozal, A. & S. Vera Gil, 2011. «Entre Europa y América latina: Mercedes Rodrigo, psicopedagoga pionera». Revista de Historia de la Educación Latinoamericana, 17 (13): 71-92.

Herrero, F., 2003a. «Mercedes Rodrigo (1891-1982): La primera psicóloga española». Revista de Psicología General y Aplicada, 56: 139-148.

Herrero, F., 2003b. Mercedes Rodrigo: una pionera de psicología aplicada en España y Colombia. Tesis doctoral (Facultad de Filosofía de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid).

Johnston, E. & A. Johnson, 2008. «Searching for the Second Generation of American Women Psychologists». History of Psychology, 11(1), 40-72. DOI: 10.1037/1093-4510.11.1.40

Russo, N. F. & A. O'Connell, 1980. «Models From our Past: Psychology's Foremothers». Psychology of Women Quarterly, 5: 11-54.

Scaraborough, E., 1994. «Recognition for Women: the Problem of Linkage». In Adler, H. i R. Rieber. Aspects of the History of Psychology in America (1892/1992). APA. New York.

Valentine, E., 2005. Beatrice Edgell: Pioneer Woman Psychologist. Nova Science Publishers.New York.

Volkmann, S. & H. Lück (eds.), 2002. Bedeutende Psychologinnen: Biographien und Schriften. Beltz. Weinheim (Germany).

Wilson, D., 2003. «British Female Academics and Comparative Psychology: Attempts to Establish a Research Niche in the Early 20th Century». History of Psychology, 6(1): 89-109. DOI: 10.1037/1093-4510.6.1.89