The coastline and Sisyphus myth

The repeated destruction of the shoreline

For issue 74, Mètode devoted some pages to the Mediterranean coast as a physical space. The present text address the same space from a different point of view. From a physical and natural perspective to a complementary and permanently intertwining one, but less structured and more conflictive: the governance and territorial management of the shoreline.

The publication of this text coincides in time with the passing by the Spanish government of the Order «of protection and sustainable use of the shores». On 5 October 2012, the cabinet gave the green light to the congress passing of the draft for the Law of protection and sustainable use of the shores and the modification of shorelines Law 22/1988, of 28 July.The law finally passed on 16 May and was published in the Official Bulletin Series A no. 29-6, on 21 May. This text represents a 180º turn in the way politics understand the use, management and sustainability of our shoreline.

Paco Tortosa

COASTAL AREAS AS SPACES OF UNIQUE WORTH AND CONFLICTS TO BE SOLVED

Regardless the legal stance adopted or the domain we assign it to, coastal areas are a territorial system. That is, they are an eminently social construct, the product of interactions and transformations of human activity on the environment to generate living spaces converted for group inhabitation.

As a result, and more than in any other territorial system, given its complex and mixed nature – with more population, more activities, more demands and between continental and maritime spaces– conflicts arise both between uses and users. If we let them evolve freely, without appropriate control (i.e., planned action, following what is now called ecosystem-based management or through new laws that promulgate the integrated management of coastal zones), they can result, as it happens, in an undesirable and unsustainable situation. That is a major issue, which we must take responsibility for, as the coastal zone throughout the Spanish territory is the natural heritage that brings more wealth to the economy (11% of GDP approximately).

«In times of globalisation, we are headed in the wrong direction, we are prioritising the private interests of the powerful over the general interest, a good quality of life and sustainability»

We can simply identify three major causes of alteration and destruction of the (continental) coast: firstly, river management (issue which unexpectedly appears to have taken a secondary role –no mentioning the implementation of the 2000 Water Framework Directive); secondly, harbour policies and facility construction as well as the controlled transformation of adjacent lands into these harbours to facilitate efficient and competitive use (as demonstrated by the statements of intent and competitive policies established throughout the Spanish ports of the Mediterranean coast, and as stated in the latest Territorial Strategy from the Valencian Regional Government). And, above everything else, urban development, which has been particularly rampant in some moments of our recent history by reiterating shapes and patterns over more than fifty years (and it seems they want to make them last). Urban development has taken over beaches, dunes and wetlands by building residential resorts, infrastructure, equipment and promenades, whose necessity is more than questionable.

These acts of aggression are made manifest in erosion and alteration of the coastline, soil and water pollution and the alteration –if not destruction- of ecosystems and close natural coastal and maritime spaces. We reach this point by hook (user pressure) or by crook (omission or neglect of compliance by the local, regional and state administrations which have or share jurisdiction of the coast zone). The aforementioned review of the Coastal Law of 1988 seems to link the two ends proactively.

In times of developmentalism, some territories found in the «Sun and sand» tourism their way towards development so they grew based on the simple but unsustainable profitability of the coast zone, regardless of its conservation. / Paco Tortosa

TRADITIONAL BUT UNINTELLIGENT MODELS OF DEVELOPMENT

Long before globalization, in the times of developmentalism, much of the Spanish territory that lacked potential for exquisite industrialization found its development path in «sun and sand» tourism; especially on the Mediterranean coast and islands. A growth based on –simple (lacking the desired feedback effects a true driving sector of regional economies would have unless associated to urbanism) and unsustainable– use of existing land resources as if they were inexhaustible. Conservation and wise usage of these resources were not priorities but facing seasonality and unstable demand were.

Strangely enough, the path for this demand to take hold was placed in the hands of large foreign operators that trivialized and standardized the offer instead of doing it well differentiated and qualified. As time went on, and with us fully entering into the economic globalization and the hegemony of generic resources .The second issue has only led itself in the same misdirection, unable to avoid some externalities that affect the use or misuse of our heritage and public property; prioritizing the interests of private companies and the powerful over the general interest, the quality of life and sustainable initiatives in the medium and long term.

«Coastal zones are eminently social constructions, the product of interactions and transformations that human activities have been taking place on the physical environment to generate living spaces»

It seems, however, that the first one has actually been reviewed with a more endogenous management of the offer. It should be noted that this has caused a very strong reaction, just as the Auken Report from the European Parliament did. It was not interesting because of the wake-up call the unfulfillment of European regulations on environmental protection meant or the suspicions regarding the dubious use of European resources; but also because it was useful in order to defend the interests of those whose taxes were being invested in Spain without getting any profits from these investment properties on the Spanish coastal area. It was a business that involved an extensive inventory of Spanish economic actors. Among these, we can find the financial sector, more particularly savings banks, many of which have been now absorbed or rescued. They own the majority of the so-called «toxic assets» in the form of mortgages, housing and promotions to be sold and, even worse, they also own many hectares of land purchased at high prices; assets with no possibilities of being relocated and valued).

BETWEEN PROTECTED AREAS AND THE INTERESTS OF OWNERS, REAL-ESTATE AND SALT INDUSTRIES

These seem to be some, if not all, of the powerful reasons that lie behind the reform of the 1988 Coastal Law. To make things more suspicious, this reform’s goals seem to be reaffirming the principles of the model that explains the recent historical development of coastal areas, restating the clear dominance of certain interests (some economic agents involved in politics publicly and shamelessly taking advantage of their status to move initiatives forward) over a consistent ordinance criteria that benefits everyone, and not just a few, in the medium and the long term rather than in the short term.

«The worse, the better. This seems to be the motto for putting things back to their place, the traditional way of making and making understand; not wanting to escape but the opposite, the only thought on how our reality should be and occur»

The coastline represents a complex and fragile space (given the interaction between two very different ecosystems –land and sea ecosystems, one with freshwater and the other with saltwater). Thus, despite succumbing on regional and town ordinance, at least it has been subject to an interventionist environmental legislation, with the subsequent declaration of a wide range of protected areas (of different type and level of protection) on the waterfront. Despite this, and despite the fact that the environmental legislation submits territorial law and conditions urban law, rulings regarding protected natural areas are not the best tool to successfully manage complex ecological and multifunctional networks that the whole coastline (protected or not) represents. The Integrated Coastal Zone Management (GIZC) has been growing stronger (it had already been formally constituted in connection with the ratification and implementation of the GIZC Protocol in the Mediterranean in March 2011) and will become the most appropriate resource. The European Union is currently drafting upcoming ICZM guidelines, which are expected to be published during 2013. Along these lines, the reform proposal of the 1988 Coastal Law also goes in the opposite direction, but it still makes time for some.

THE UNCOMFORTABLE 22/1988 COASTAL LAW; A NUISANCE THAT MUST BE SOLVED IN TIMES OF ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL CRISIS

Within the time frame that we have referred to throughout this article, an early Coastal Law from 1969 had the purpose of regulating, albeit without much success, the use of maritime goods of public domain. Years later, the 1980 Law on Protection of the Spanish Coasts sought to strengthen a protectionist role, focusing exclusively on public property. The original 22/1988 Coastal Law became the basic regulatory framework to establish the maritime-terrestrial public domain (also known as DPMT), ensuring its integrity and conservation. It was also used to ensure its public use, to regulate the rational use of the land (according to its nature and purpose and respecting the landscape, the environment and historical heritage) and to keep an appropriate level of quality of both water and seashore.

The Law has been repeatedly dealing with obstacles and conflicts (either unexpected or forced) with both individuals and other government departments (local and regional). As an example, we can highlight the tortuous process of demarcation (especially in the province of Alicante). That has kept it at bay and has given the time needed until now, when some are trying to go back to old philosophies, practices and ways (some people have found parallelisms between the ideas that lie behind the reform draft and those who enacted the Cambó Law in 1918!). The sword of Damocles, which was menacingly hovering for so long, ended up falling and trying to suddenly tackle all the efforts that the previous General State Administration had been making. A new and very illustrative example that shows us how absent statesmanship is.

The draft text literally recognizes the necessity of revising the 1988 Law «from a conciliatory vision that ensures the protection of the coastline and endows with genuine legal certainty the relationships that are being developed.» Issues such as the prolongation of the terms of concession agreements within the DMPT (75 more years); update and revision of the refusal of liabilities; the possible reduction of the access easement area (In Spain, known as ZSP) from 100 to 20 m from the shoreline (for example, in not necessarily urban areas but that present urban characteristics –thus legalising what is outside the actual law); revisiting time criteria and periods of recurrence of large swells, limiting them to just ten years and with a frequency of at least four episodes in this short-term; as well as amnesty or exemption in specific parts of the coast (a total of between seven and ten on the Mediterranean coast and three in the province of Huelva) with no apparent reason except building a first series of Trojans that justify, by analogy, expanding the number of exemptions in future cases. These are all issues that present a new situation, and we can also think of rights and the relationship between public and private interests.

A careful reading of the draft text makes the intention of protecting holder’s property rights clear. Reducing the DPMT and ZSP to a minimum; but not for the sake of privatising, which could facilitate the possibility of defrayal of security measures and damage restoration by beneficiaries (or their insurers). Thus, in contrast, the State (also as landlord and dealer, responsible for giving market value to public resources) remains responsible (apparently through externalisation) of their protection, maintenance and, when appropriate, restoration. It is only in this way that the law seems to understand sustainability.

Port policies have serious consequences, such as erosion and alteration of the shoreline, water pollution or alteration of ecosystems and maritime areas. / Paco Tortosa

TOWARDS A NEW CULTURAL AND TERRITORIAL POLICY: SOCIOTERRITORIAL INNOVATIONS MUST BE BOTTOM-UP

The effort and progress made until recently seem to be of little importance so far; either from the point of view of investment and material transformations, or of economic and personal costs of equipment and local, national or even international officials (in the form of conventions, protocols, guidelines or investment funds from initiatives, projects and programs for the Mediterranean supported by institutions like the EU or the UN itself).

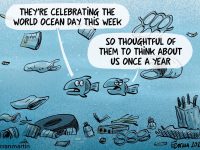

«Stop and go», or vice versa, seems to be the mentality in which our country remains immersed. Wasting and wasting out, without even caring if we are undergoing a crisis, as it has historically happened at the end of every growth cycle. The worse, the better. This seems to be the motto for putting things back to their place, the traditional way of making and making understand; not wanting to escape but the opposite, the only thought on how our reality should be and occur. And this happens at all scales: from the political to the economic scale, from justice to natural sustainability and from society to the way democracy works.

In the subject of coastal management as well as other issues such as water and state model, to mention some very crucial ones, the short-term political (in)culture and political strategy of polarization and conflict have primacy over consensus, pact and statesmanship. As an old Chinese saying points out, if we are not able to change direction, it will probably drive us back to where we aim. So where are we going? The current situation in which we find ourselves has already begun to take enough samples of structural violence: progressive loss of rights and values and a crisis of democracy. Violence which society has already begun to demonstrate, to organize and resist to. How long and how far will it take us? This should be our priority in the agenda and the task of decision makers and true policy makers; but here suspicions arise again.

In Spain, the coastal zone is the natural heritage that brings more wealth to the economy (about 11% of GDP). / Paco Tortosa

Territorial systems, including coastlines, are ours and we can make use of them. However, we must make good use of it, «prudent and creative», as the ESPON states. We must keep on raising awareness among the population, and encourage (if not directly require) the most powerful economic actors, who make use of all our assets and resources, to ensure their corporate responsibility (and not just social responsibility or reduced to the management phase, but also territorial and environmental responsibility, extended to the effects of territorial impacts of each initiative). This corporate responsibility should end up causing the proper effect on the rest of actors and present uses in the territory (contrary to what is happening right now, when the lesson that is taught is the opposite).

Finally, and most importantly, the law must be complied with, especially by the administrations. Otherwise, they will face -everybody will have to- charges of breaching EU dictates such as the Water Framework Directive, or protocols such as Integrated Coastal Zone Management in the Mediterranean (which in Article 8.2 establishes no less than 100 m of protection and limits the inventory of uses); both of which are binding and compulsory in the Spanish territory. And society (because of the socialisation of losses while continuing pooling profits, as usual) will continue to pay the consequences of not following the recommendations that include adaptation to climate change in the instruments of local and regional planning, and to face natural and man-made hazards with minimum guarantees.

Hard times cannot be an excuse to make us lose perspective; on the contrary, they have to make us refine alternatives and ensure that we take steps in the right direction. We must be more vigilant and committed than ever, and actively participate to politicize and inform. If we have an agreement, let’s go; if not, let’s fight.