Ancient Greece is the birthplace of western culture, in political organization and philosophy, mathematics or natural history. But even such popular stories as the legend of Saint George, who seems genuinely Catalan, could have originated in Greek mythology.

Andromeda freed by Perseus, painted by Dutch artist Joachim Wtewael in 1611.Renaissance painters often associated, erroneously, the flight of Perseus with the winged horse Pegasus. In the tradition of Greek myths, Perseus flies with his winged sandals. / Louvre Museum, Paris

The myth of Perseus and Medusa

Perseus was a hero, son of Zeus and the mortal Danae, and lived on the Greek island of Serifos. One day king Polydectes entrusted an almost impossible mission to him: he had to take the head of a Gorgon as a gift so the king could impress the woman he loved. The Fates or Gorgons were three monstrous sisters, equipped with wings and with snakes on their head instead of hair. Of the three of them, Medusa was the only mortal and had the power to petrify anyone who looked at her eyes.

Like all heroes, Perseus had the favour of the gods and received help from his father, Zeus, but also from Hermes, Athena and the Stygian nymphs. There are different versions of the myth about what each of them provided, but they all agree that Hades gave him a helmet that made him invisible. He also wore flying winged sandals, a polished shield to protect himself and at the same time to look safely at Medusa’s reflection, an unbreakable sword and a magic pouch to store the head of Medusa and avoid the petrifying gaze.

Perseus flew to the land of the Hyperboreans and located the cave where the three Gorgons lived. When he entered the cave he found them sleeping among the petrified remains of humans and beasts. Looking at the reflection on the shield he identified Medusa, got closer and beheaded her. The winged horse Pegasus and the giant Chrysaor were born from the wound. The other two Gorgons awoke, startled, and chased Perseus to kill him, but the hero was able to escape thanks to the invisibility helmet.

On the way back, Perseus stopped in the kingdom of Ethiopia, located on the coasts of Israel or Lebanon. That kingdom was ruled by King Cepheus and his beautiful and vain wife Cassiopeia. To punish the vanity of the queen, Poseidon sent a great flood and a sea monster named Cetus to lash the coast. An oracle had announced that there would be no remedy until Andromeda, daughter of the king, was delivered to Cetus. Perseus found the princess chained to a rock on the shore just as Cetus emerged from the sea to devour her. Then he stabbed the monster in the back with his sword or, depending on the version of the story, petrified it using Medusa’s head.

«The tale of Saint George is the result of an accumulation of pagan traditions. That did not stop its assimilation into Christianity, which needed heroic characters to facilitate the process of evangelization»

Back to Serifos, Perseus discovered that Polidectes had entrusted him the mission so he would be away from his mother, and marry her by force. After defeat, Perseus returned the borrowed magical items and gave Medusa’s head to Athena, who since then wore her image on the shield. He married Princess Andromeda and fathered seven sons and two daughters. His firstborn, Perses, stayed in Ethiopia and became the ancestor of the Persians.

The legend of Saint George and the dragon

Saint George was born precisely in a region of the Persian Empire. Tradition places him circa 280 in Lydda (Diospolis for the Romans; now Lod, Israel), son of Gerontius, a Roman officer, and Polychronia, a local girl. Upon reaching adulthood, Georgios (Greek for «worker of the land») enlisted in the Roman army, following in the footsteps of his father. When he was thirty, he was stationed in Nicomedia as tribune and joined the personal guard of Roman emperor Diocletian. In 303, the emperor persecuted the Christians, but tribune George refused to act and confessed that he was also a Christian. Diocletian, who valued him very highly, tried every means to convince him of abandoning Christianity and adopting Roman deities, but George flatly refused. The emperor had no choice but to sentence him to be tortured and finally beheaded on 23 April. Once dead, his body was returned to Lydda to be buried.

«The Catalan version of the legend adds that from the blood gushing from the wound a rose bush full of roses was born and St. George gave it to the princess»

This story seems more legendary than true and is the result of an accumulation of pagan traditions. Anyway, that did not stop its assimilation into Christianity, then an emerging religion that needed heroic characters to facilitate the process of evangelization. Worship and devotion to Saint George soon began among the early Christian communities of the Eastern Roman Empire, which led to the construction of dozens of churches and temples and the pilgrimage to his grave. At the beginning of the fifth century, its popularity reached the western part of the empire and in the year 494 he was canonised by Popoe Gelasius I. In the sixth century he was already worshiped in the Frankish Kingdom. With the Early Middle Ages and the Crusades, the worship spread to the rest of Europe.

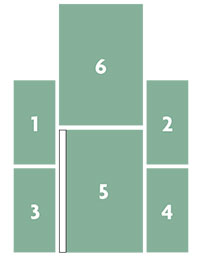

Probable arrangement of the six sections of the altarpiece of Saint George, painted by Catalan artist Bernat Martorell between 1434 and 1437.The side pieces (1-4) are The Proconsul Dacian Sentencing Saint George, Saint George Dragged through the City, The Flagellation of Saint George and The Beheading of Saint George. They are preserved in the Louvre, Paris.The centrepiece (5) is Saint George Killing the Dragon, and is preserved at the Art Institute of Chicago. It is assumed that another tableau is missing on the left side (5b). And the upper part (6) is the Enthroned Virgin and Child, with the Cardinal Virtues and Two Figures Holding Scrolls, located in the Philadelphia Museum of Art.The proportions have been preserved. Made from Alcolea (2007) and Kientz (2012).

In the eleventh century we can first find the story of George on horseback defeating a dragon. The details of the tale vary depending on different traditions of Europe, Asia Minor and even Japan. The western medieval legend describes a fierce dragon who built its nest on the spring that provided water for the city of Silene, in Libya. Citizens had to drive the dragon away from the spring every day in order to get water. So every day they offered a sheep in sacrifice. But when they started to run low on sheep, they began offering virgin girls chosen by lot among the population. One day princess Cleodolinda (or Trabzon), daughter of the king, was chosen. When she was about to be devoured by the dragon, Saint George appeared, riding on a beautiful white horse, drove his spear through the scales of the dragon and killed him. The Catalan version of the legend adds that from the blood gushing from the wound a rose bush full of roses was born and Saint George gave it to the princess. From that moment the grateful citizens abandoned paganism and embraced the Christian religion.

As a Christian soldier, Saint George became the patron saint of knights and soldiers, and the protector of several military religious orders such as the Templars or the Teutonic Knights. At the end of the Middle Ages he became also the patron of cities, villages and manor houses across Europe. King Peter I of Aragon named him not only patron saint of chivalry, but also of the nobility of the kingdom of Aragon, having favoured the victory against Muslims during the Battle of Alcoraz (Huesca) in 1096. This patronage was later extended to the Crown of Aragon, and in 1456 the Catalan Courts also formalized the patronage of Saint George declaring 23 April as a holiday.

The story of a Saint George altarpiece

Shortly before this date, between 1430 and 1437, the Council Office commissioned an altarpiece of Saint George by the prestigious painter Bernat Martorell, very famous at the time, to decorate the chapel of the Council Office (now Palau de la Generalitat). The painter outdid himself and painted what is considered his masterpiece. The altarpiece seems to have originally consisted of six parts: four side pieces with scenes of the martyrdom of Saint George, a centrepiece with the famous scene of the saint slaying the dragon and a top piece devoted to the Virgin. But this story, explained and solved in a few lines, is actually much more complex and has been subjected to all kinds of events that affect both the identification of the painter and the sections of the altarpiece. A 1499 inventory guarantees that the work was still in the chapel, but it abandoned the Palau de la Generalitat during some war or political instability and disappeared for over 350 years. In 1867 it reappeared as part of the collection of Francesc Rocabruna, Baron of L’Albi. In 1887, Dupont, an antiquarian, acquired the four side pieces and sold them three years later to Théophile Beline, which in turn sold them to the Societé des Amis du Louvre. They were finally donated to the Paris museum in 1905. The centrepiece became part of the collection of Ferran-Vidal i Soler in 1906, before being purchased by Deering and later transferred to the Museum of Chicago in 1917. And the top piece joined collection of John G. Johnson and was transferred in 1917 to the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Thus, in the early twentieth century the altarpiece was dismembered and ended up distributed in the Louvre, Chicago and Philadelphia museums.

(Left) The common gecko (Tarentola mauritanica) is a reptile from dry and warm Mediterranean regions. It inhabits dry walls or rocky ground. Therefore, it is closely associated with man in both rural and urban environments. He is often seen at night near streetlights or bright spots where they hunt insects, and sometimes they even come in closets chasing moths. That is why it is also known in Catalan as «menja-robes» (clothes eater), although they do not really eat clothes but the insects that feed on them. It is, therefore, a very common animal and as popular today as it must have been at Bernat Martorell’s time. / Guillem Pascual

(Right) The common seadragons (Phyllopteryx taeniolatus) are native of the southern coast of Australia and related to seahorses. They live in shallow waters, especially in seagrass meadows. Like many other species in this group, the males carry the eggs until they hatch. They have a reddish color with yellow spots and curious leaflike appendages that allow them to blend into the environments where they live. / Andy Thirwell

Detail of Saint George Killing the Dragon, center section of the Altarpiece of Saint George by Bernat Martorell.The usual iconographic interpretation holds that the set should represent the martyrdom of the saint, the maiden should be Alexandra, the wife of Emperor Diocletian, converted to Christianity under the influence of the saint, and the dragon should be Satan and the Roman Empire. This composition became canonical and was widely reproduced by many later painters. But no one paid attention to a zoo-linguistic detail: Martorell painted three small dragons (geckos) at the foot of the princess, in all probability to make a pun with “drac” and “dragó”.

The Art Institute of Chicago

But Martorell actually left some clues in his work that clearly identify its birthplace. One of these clues was discovered by the technicians of the Philadelphia Museum of Art when they restored the centrepiece of Saint George Killing the Dragon. Under the wings of the dragon he painted a few small fragments of newspaper written in Catalan. And there’s a second clue that went unnoticed until now: at the feet of the princess and the sheep, Martorell depicted three geckos, most likely a pun between drac (“dragon”) and dragó (“gecko”). This duplication of terms with a common, often used indistinctly to describe both the savage beast and the harmless critters, do not exist in any language other than Catalan and was surely in effect at the time the picture was painted because Ramon Llull already used it 150 years earlier. It is unclear, however, why three dragons and not any other number of them.The Holy Trinity? Three temptations? Three territories ruled by the Government? Three friends of the painter?

Consequently, in addition to documentary sources, pictorial style, iconography, the size of the pieces, the type of wood and pigments, there are certain linguistics and zoology details that provide useful data to reconstruct the fascinating history of this Gothic altarpiece.

The zoology of dragons

«The representation of the dragon as a reptile is very recent. It changed significantly over the centuries. It has been painted as a snake, a demon or with mammalian traits»

It does not take an expert in zoology to know what a dragon is like. Even young children know how to draw one in the finest details. It is a green animal, covered with scales, with a pair of membranous wings, a ridge that runs along the top of its head, back and tail, a mouth full of crocodile teeth, forked tongue, with large claws in its short legs, feline eyes… And obviously with the ability to breathe fire when angry. If we were to classify it, we would not hesitate to consider it a reptile. But this is a very recent representation. The dragon of Saint George changed significantly over the centuries. It has been painted as a snake, a demon or with mammalian traits. Its origin in Greek mythology has been blurred, but the mythological terms remain: Medusa, gorgons, and cetaceans designate different marine animals today. And surely the closest animal to the legendary beast Saint George killed is not a reptile but a small fish related to seahorses, native to the tropical coasts of Australia: the seadragon. It is such a dragonlike animal that were our cultural cradle the antipodes instead of Greece, Saint George would have possibly been a fisherman rather than a knight.

Acknowledgements: Rafael Cornudella, Guillem Pascual, Andy Thirlwell, Cari Pardo.

REFERENCES

Alcolea, S., 1985. El Pintor Bernat Martorell (...1427-1452). Ajuntament de Sant Celoni. Sant Celoni.

Alcolea, S., 2007. «El retaule de sant Jordi de Bernat Martorell, a París, Xicago i Filadèlfia». In Bracons J. and J. Mestre. Art català al món. Edicions 62. Barcelona.

Cirlot, V., 1987. El Drac en la cultura medieval. Fundació Caixa de Pensions. Barcelona.

Hartfield, R.; Eskridge, R. W. and M. F. Farr, 1998. Bernat Martorell. Saint George Killing the Dragon, 1434/35. The Art Institute of Chicago. Chicago.

Kientz, G., 2012. «Bernat Martorell. Quatre compartiments del Retaule de sant Jordi». En Cornudella, R. (ed.). Catalunya 1400. El Gòtic Internacional. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. Barcelona.

Ribas, A., 2012. «L’última peça del trencaclosques del ‘Retaule de sant Jordi’». Ara, 10 d’abril.

Ruiz, F., 2002. Bernat Martorell, el Mestre de sant Jordi. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. Barcelona.