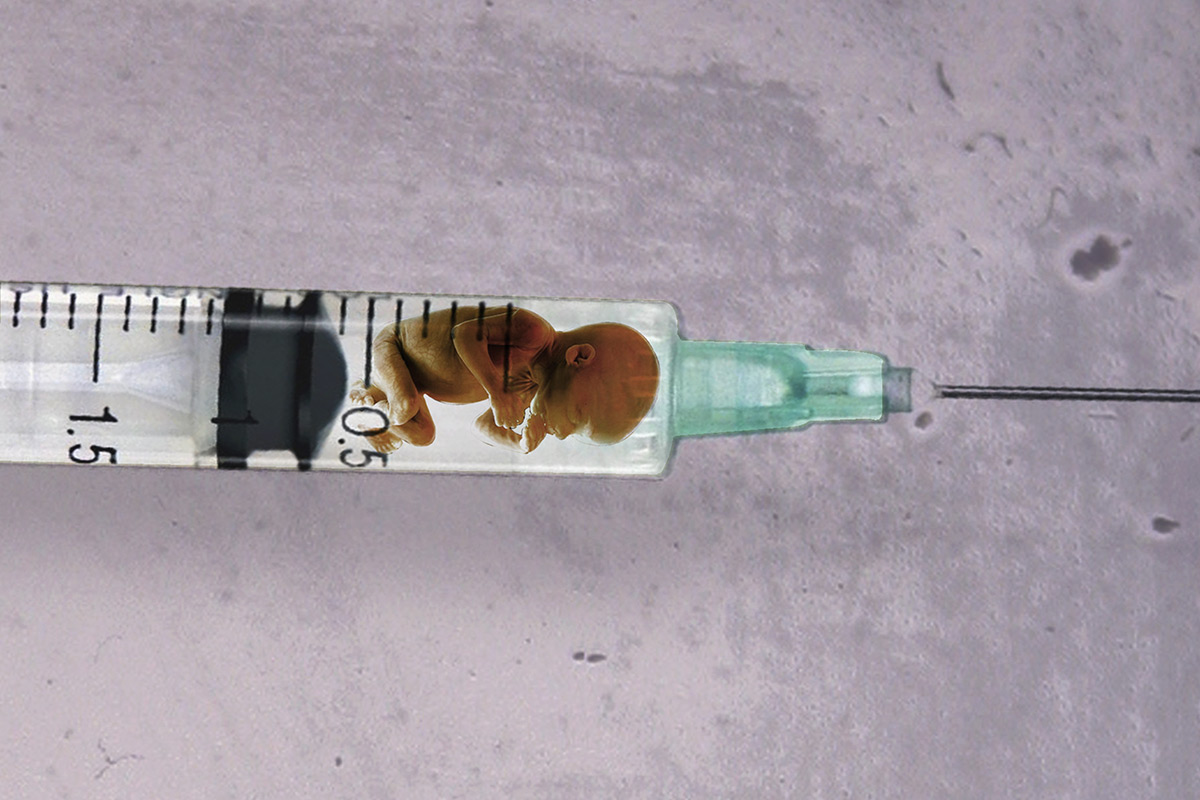

The problem

There are various medical conditions that make women lose babies during pregnancy. That is why several enlightened countries facilitate the transplantation of foetuses either free or at token cost. Unfortunately, Spain is not one of them but many women and groups think it should be. Becoming a mother or father is simply too important to allow red tape to stop volunteers from helping couples have a child. That is why the issue needs debating. For many people, becoming a parent is the most important thing in the world. Actresses such as Angelina Jolie, Kate Winslet and Julia Roberts (who one supposes want for nothing) say it is what they set their hearts on. In this respect, maternity makes us equal. Yet what these high-rollers really want is virtually within the grasp of any woman.

«Becoming a mother or father is simply too important to allow red tape to stop volunteers from helping couples have a child. That is why the issue needs debating»

However, motherhood also makes us unequal because a minority of women cannot achieve what others consider a priority. It is especially painful when what passes as the best, most normal thing in the world lies beyond our reach. Nobody kicks up a fuss about not being like Angelina Jolie —it is something one accepts as natural. By contrast, being infertile not only deprives one of children but also makes one feel abnormal. While there are ‘normal’ people who do not want children, others yearn for offspring so strongly that they are willing to risk their careers, money and health for the patter of tiny feet. There are rumours that both Angelina Jolie and Julia Roberts carried out hormone therapies so that they could have twins. Other women undergo medication, operations and high-risk pregnancies, chalk up one failure after another, seek solutions abroad, suffer financial ruin, feel guilty, split up from their partners or stick with them for longer than they should. In other words, they suffer horribly both physically and mentally. That is why we have to consider the solutions available.

© John French

The solutions

Fertility clinics can help through assisted reproduction and the donation of eggs and sperm. This aids many women who could not otherwise attain pregnancy. However, this does not help those who cannot complete gestation. Let us take a hypothetical couple – Maria and Manel – as an example. Maria gets pregnant easily but loses babies during term. The first time round, she landed in the emergency ward after being admitted with heavy bleeding. Her friend Anna, who already has two children, offered to act as host for Maria’s embryo for the latter part of the term, when the risk of spontaneous abortion is greatest. The couple thought that if this worked, they would be willing to pay the school fees for Anna’s mentally handicapped daughter. Anna found it hard to meet these, given that her daughter had to attend a special centre. Under such circumstances, there is no reason for considering their behaviour immoral. It cannot remotely be labelled as baby-trafficking. In this case, Anna merely stands in for Maria during a few months of the pregnancy. Now let us consider that for medical reasons, the sooner the transplant is made, the greater the chances of a successful birth are. In this case, it would be immoral to insist that Maria bore the pregnancy for the first few months. Let us now suppose that: (1) the couple met Anna in a clinic where other couples ask for the same help; (2) Anna decides to help Maria and Manel because she trusts them and they are willing to meet her daughter’s schooling fees.

«There are countries where the host mother may also be the biological one. This greatly complicates matters»

People‘s motives for helping vary. Thus the fact that a doctor charges us for his services does not mean his motives for curing us are purely mercenary. One motive does not necessarily rule out another. Anna may well want to help the couple anyway and the offer of having her daughter’s school fees paid is just another reason. It is also natural that the couple should want to express their gratitude in more than just words. So far then, there is nothing unbecoming or immoral in the agreement. All parties have been properly advised on medical, psychological and legal matters and the whole process has been carefully supervised throughout. For example, Maria and Manel wanted to make sure that Anna’s two pregnancies had gone off without a hitch and that she had followed all medical advice to the letter and attended all check-ups both before and after the births. They also wanted to establish penalties for any breach of the agreement, register the foetus’ legal and genetic status and ensure there were no hormonal incompatibilities. Anna also wanted to make sure the couple did not welsh on the agreement. She also wanted to maintain her anonymity or – should her identity be revealed – have the opportunity to see the child from time to time. It was a matter where everyone’s wishes were compatible and nobody raised objections on key issues.

«While it may not fully protect those involved, denying women legal regulation in this field only leaves them even more defenceless»

There are countries where the host mother may also be the biological one. This greatly complicates matters. One needs to be rigorous, establishing among other things, how Anna should be compensated in the event of an ectopic pregnancy or if she has to be admitted to hospital, what happens if she has twins or the doctors recommend abortion, and so forth. Everyone ought to be aware of these risks before pregnancy occurs and in cases such as this, one needs to be prepared for every contingency. Put another way, it is one thing to ask a neighbour for salt and quite another to ask her to provide all the ingredients and then cook dinner. However, given that the host mother is not necessarily the biological one or even the person bringing up the child, we do not need to consider all possible cases at the same time. Let us therefore concentrate on the case of Maria and Manel, who have decided together that Anna will bear their baby girl, to whom they have given the name ‘Mia’. Article 10 of Spain’s Aided Reproduction Act 14/2006 of 26th May states that “Any contract for pregnancy with a woman who renounces her maternal rights over the child in favour of a third party shall be null and void whether or not any consideration is involved”. Furthermore, the Act determines the woman giving birth to the child has legal title to it and only makes the caveat “save for any claim made by the child’s biological father”. This makes no sense if the embryo is Maria and Manel’s because if the father has to conserve his rights over his issue, it makes no odds whether or not Anna covers the second part of the pregnancy.

© John French

Granting paternal rights but not maternal ones clearly discriminates against women. This is unjust when any man enjoys such rights merely by virtue of his gender and irrespective of the circumstances in which he fathered the child. Anna will not see the baby while she bears it and once born, it will be like any other and not look like her. In fact, it will look like Maria, the woman who conceived and wants to bring up Mia. This is hardly surprising because the egg from which the baby grew is Maria’s. It will be Manel and Maria who take care of the child and who, in the fullness of time, become the grandparents of Mia’s offspring. That is to say, Maria is both the biological mother and the de facto mother. Alternatively, one could argue that Mia has two mothers (Maria and Anna) and that if she can only have one, it should be Maria, even though the Law says it must be Anna. In any event, the matter could be solved by signing an adoption contract on Mia’s birth or even a little while afterwards. Of course, there will be people who fail to reach agreement on the compensation payable in the event of breach of contract. In such cases, one needs to find a more compatible host mother. There is thus no need for a law setting out every conceivable eventuality and the compensation payable in each case. Instead, a general act setting maximum and minimum damages for breach of contract would suffice, with the precise amount being stipulated in the accord. This would cover the biggest risk —namely, that someone has a change of heart. Given that Manel and Maria are so desperate to become parents, the likelihood of this happening is less than in an unplanned pregnancy. It would also be strange if interruption of their pregnancy were allowed in the short time between transplantation of the foetus and the end of term or that Anna changed her mind. Furthermore, one could also agree on irrevocable adoption before the birth or, alternatively, run the risks of breach of contract. In any case, while such agreements may not fully protect those involved, denying women legal regulation in this field only leaves them even more defenceless. We therefore have to focus the discussion on how to deal with each risk of breach of contract. Nevertheless, the objections most often raised to legal regulation of surrogate pregnancies are also the least relevant, as we shall see below.

© John French

Unnecessary use

One of the commonest objections raised to such agreements (and repeated ad nauseum on the TV show La Noria) is that many women also resort to this system to keep their figures. This is a very weak argument because only cases where there was a proven medical need would be admitted. Forbidding Maria from entering into such an arrangement on the off-chance that a film star might copy her actions purely for aesthetic reasons is like forbidding plastic surgery merely because a few women resort to the scalpel with wild abandon. In any case, film stars recover splendidly from pregnancy so why should they court unpopularity by contracting someone else to have their baby? Besides, the paparazzi would have a field day with such a story and neither the stars nor the surrogate mothers would get a moment’s peace. The woman who bore Sarah Jessica Parker’s twins had her telephone tapped and Nicole Kidman is criticised for ‘not having tried hard enough’ to have a normal pregnancy.

Potential exploitation

It makes no sense to fret about the stars but it does to worry about poor women who are vulnerable to exploitation. This is a real problem and is much graver in other cases, such as prostitution. Maybe being able to act as surrogate mother actually makes women less vulnerable, even though possibly only the poorest or most altruistic of them is willing to act as such. It is therefore hard to see how denying this option helps the poor. Furthermore, as well as the satisfaction of helping others, surrogate mothers enjoy the protection afforded by ongoing medical, psychological and legal support and also make a tidy sum into the bargain – some fifteen to twenty thousand euros in Spain or some one hundred thousand dollars abroad. One should bear in mind that reforming the aforementioned Article 10 of the Act would not give rise to a free market but rather merely allow certain contracts guaranteeing a minimum fee. The greater the financial reward for a surrogate mother, the less exploitation and the greater the coverage of risks there will be, on the one hand, and the less likely it is that someone will choose surrogate pregnancy instead of adoption.

«Being unable to have or adopt children is particularly sad in this country because despite their many defects, spaniards lavish great care and love on children»

The impact on adoption

The third and most common objection raised to surrogate pregnancies concerns the millions of children up for adoption. This means that although Maria could easily adopt instead, the same argument could be made for fertile women yet nobody dreams of forbidding them from bearing children. Do surrogate pregnancies increase suffering because they cut the number of adoptions? Do waifs suffer more than infertile Spanish women? One must admit both possibilities. Yet moral obligations towards the world’s children concern us all, not just barren women. The fact that it costs more for some women to bear children than others does not make adoption any cheaper. Perhaps someone like Maria, desperate to have a biological child, would have to renounce more than others if she were to adopt. Other parents, for whom a biological child is the least of their concerns, would lose less through adoption. We cannot ask Maria to do something for the world’s children that we are unwilling to do ourselves. Hence, it is specious to argue that in her case, the difference between reproduction and adoption is of lesser importance. Given Anna’s willingness to act as a surrogate mother, the only thing that sets Maria apart from other women is our permission. It would be another matter altogether if the couple needed both eggs and sperm. In such cases, it makes more sense to adopt a child who needs us and whose lot we can greatly improve. Here, one can also see the child before deciding whether or not to adopt it. However, Maria’s case is different. She can create eggs and if we deny her the option of a surrogate pregnancy, she will continue trying to bear children. Let us consider another possible objection. Perhaps Maria would not adopt a child in any case but her example may lead others not to adopt either. This too is possible but one should bear in mind that if Spaniards do not adopt more children, this cannot always be ascribed to lack of will. There are costs involved (ranging from eleven to fifty thousand euros), waiting lists (from two to eight years) and other barriers too (for example, in some countries single-parent, homosexual and atypical families are barred from adopting children). Elton John, for instance, took the surrogate pregnancy route when the Ukraine turned down his application to adopt an HIV-positive child and his sister. The reasons for the rejection were Elton John’s age and his bachelorhood.

The combination of these barriers and limits on the number of adoptions imposed by certain countries means that if Maria were to adopt, she would simply deprive someone else of the chance of having a child (assuming that person could not bear children). Perhaps if Maria were allowed to save one of her embryos, she would be willing to contribute financially to enable another woman to adopt a child. This would offset any negative impact her example might set regarding adoption. Such an approach would benefit everyone and could help narrow the cost gap between ‘wombs for hire’ and adoption.

«The greater the financial reward for a surrogate mother, the less exploitation and the greater the coverage of risks there will be on the one hand and the less likely it is that someone will choose a surrogate pregnancy instead of adoption»

Other solutions

Outlawing surrogate pregnancies is thus neither the best or the only way of boosting adoption. Adopters could be given greater financial aid, translation and management services. Furthermore, adoption procedures could be computerised to facilitate monitoring of the process. Taking on more staff could also help cut the waiting time for adoption. At the moment, getting a letter certifying the suitability of adoptive parents takes ages and the post-adoption monitoring process is sheer torture. Cutting out some of the red tape would both speed things up and make adoption cheaper. The fact that some would-be adopters jib at jumping through endless administrative hoops is a positive sign. There are improvements that do not depend on Spain. In all fairness, one should note that Spain does have redeeming virtues, for example: its equal treatment of home and foreign adoption; its many international agreements; its helpful, well-trained civil servants.

However, the present lack of national co-ordination makes no sense at all. Sending applicants to the back of the adoption queue whenever they move from one region of Spain to another is perverse. Furthermore, Spanish embassies could provide much more legal and medical support to adopters by, for example, funding proof of donor parenthood where this is a hurdle to adoption. Being unable to have or adopt children is particularly sad in this country because despite their many defects, Spaniards lavish great care and love on children. That is why we need to tackle the issue of surrogate pregnancies as a matter of urgency. We need to hold a rigorous debate on such agreements and adoption services. After all, Spain is a paradise for children with its sunny climate, innumerable parks and play areas, people willing to give a helping hand with push-chairs and who shower children with kindness. No doubt Angelina Jolie, Julia Roberts and Kate Winslet wish they too lived in a country where kids are received with open arms.