Too many bears and penguins

Cartoons forget indigenous fauna when they warn of the risks of climate change

Sara Moreno, Tatiana Pina and Martí Domínguez, researchers at the University of Valencia, have shown the over-representation of iconic animals of climate change, such as polar bears and penguins, in cartoons that address the climate emergency. In a scientific article, for which they have reviewed 1,022 of these illustrations, they conclude that, regardless of their geographical origin, cartoonists tend to avoid the use of native animals and show very little biodiversity in their drawings, especially in terms of insects and other invertebrates.

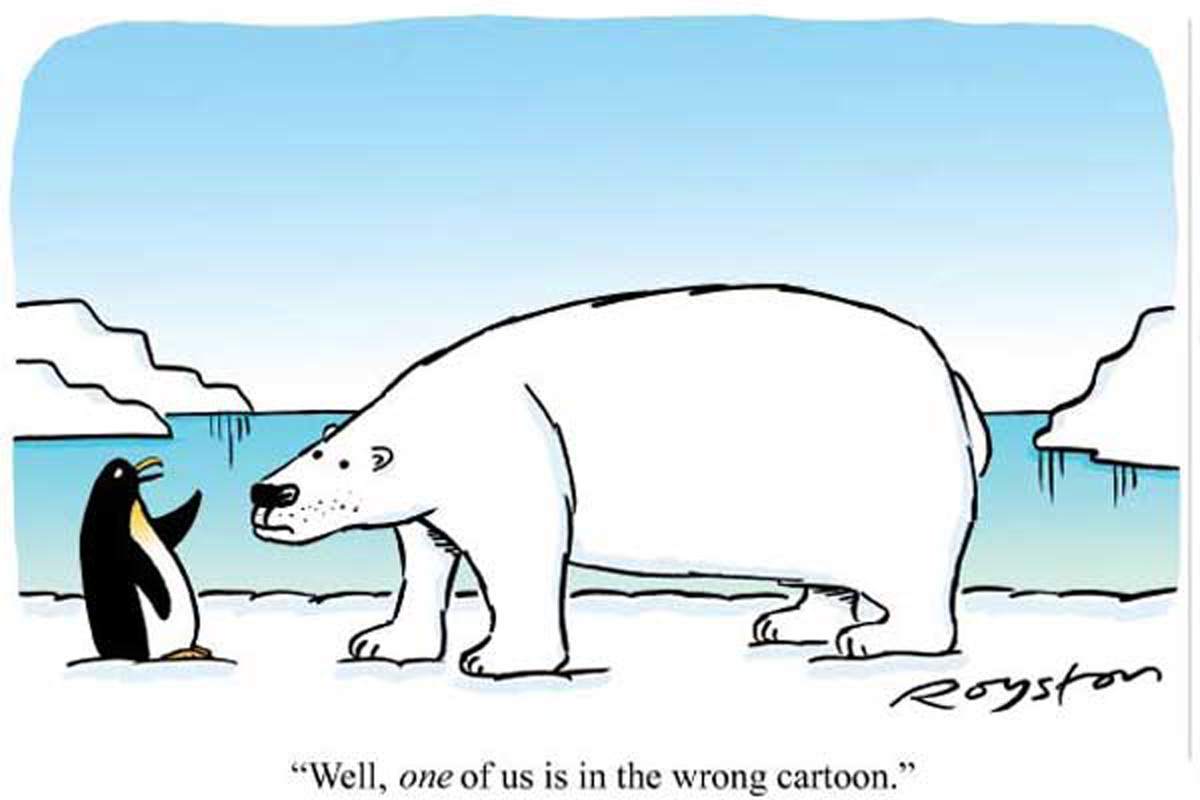

The polar bear and the penguin are the species most used by cartoonists around the world when illustrating animals in cartoons about climate change. Instead, native fauna is especially absent in these illustrations. This is the main conclusion of the work Worlds apart, drawn together: Bears, penguins and biodiversity in climate change cartoons, recently published by Sara Moreno, Tatiana Pina and Martí Domínguez in the journal Public Understanding of Science. The article has examined the presence, typology and use of animals in cartoons dealing with climate change signed by authors from 60 countries, including representation from the five continents.

The study encourages cartoonists to use native fauna in their illustrations to improve communication about climate change in their cartoons, as well as to also represent invertebrate fauna, given that despite being the most abundant on the planet and the most currently affected by the climate crisis hardly appears in the cartoons.

In addition, the work recommends avoiding the dissemination of erroneous ideas, since “some serious biogeographic errors have been detected”, warns Sara Moreno, a graduate in Biotechnology, PhD candidate in Communication and Interculturality and first author of the article. One of these errors is the representation of the polar bear and the penguin in the same ecosystem, since “the polar bear lives in the Arctic, in the Northern Hemisphere, while the penguin will be found in Antarctica and other southern lands, that is, in the Southern Hemisphere”, explains the researcher.

The work also encourages cartoonists to develop a communication on climate change contemplating the possibility of a future that is not exclusively the most feared. “All the cartoons studied present a single scenario: one in which the worst of the consequences of the climate crisis could not be avoided”, explains Moreno. This fact “leaves no room to imagine solutions that mitigate the problem and may invite the user of these illustrations to settle in a position of immobility in the face of climate action”, concludes the researcher.

“Cartoons can be a very useful tool to analyse the public’s perception of any topic”, explains Martí Domínguez, professor at the Faculty of Philology, Translation and Communication and director of the Mètode magazine. In addition, “cartoons also influence the creation of public opinion, especially on current issues, and the climate issue is a clear example”, clarifies the researcher.

Graphic humour is very present in the illustrations studied. “It is a very efficient mechanism to bring a matter of public interest to a large number of potential readers”, says Domínguez. “Graphic humour is a very interesting object of study when you want to study issues that involve a certain social criticism”, says the researcher.

Tatiana Pina, researcher and professor at the Faculty of Teaching at the University of Valencia, highlights the special effort that should be made from all institutions, and especially from schools, to “include both formal and non-formal education the study of climate change and its consequences”, while“ providing students with tools to know how to act in the face of this serious climate crisis”.

Therefore, the work suggests that predominantly using animals far from the local collective imagination could produce a geographical distance in the social perception of climate conflict and, as a consequence, reduce the motivation to take action and mitigate the problem. On the other hand, the researchers also warn of the possibility of creating a false perception of temporal distance regarding climate change if animals are illustrated in extremely devastated scenarios, by suggesting that the consequences of global warming on their ecosystems are still far from occurring.