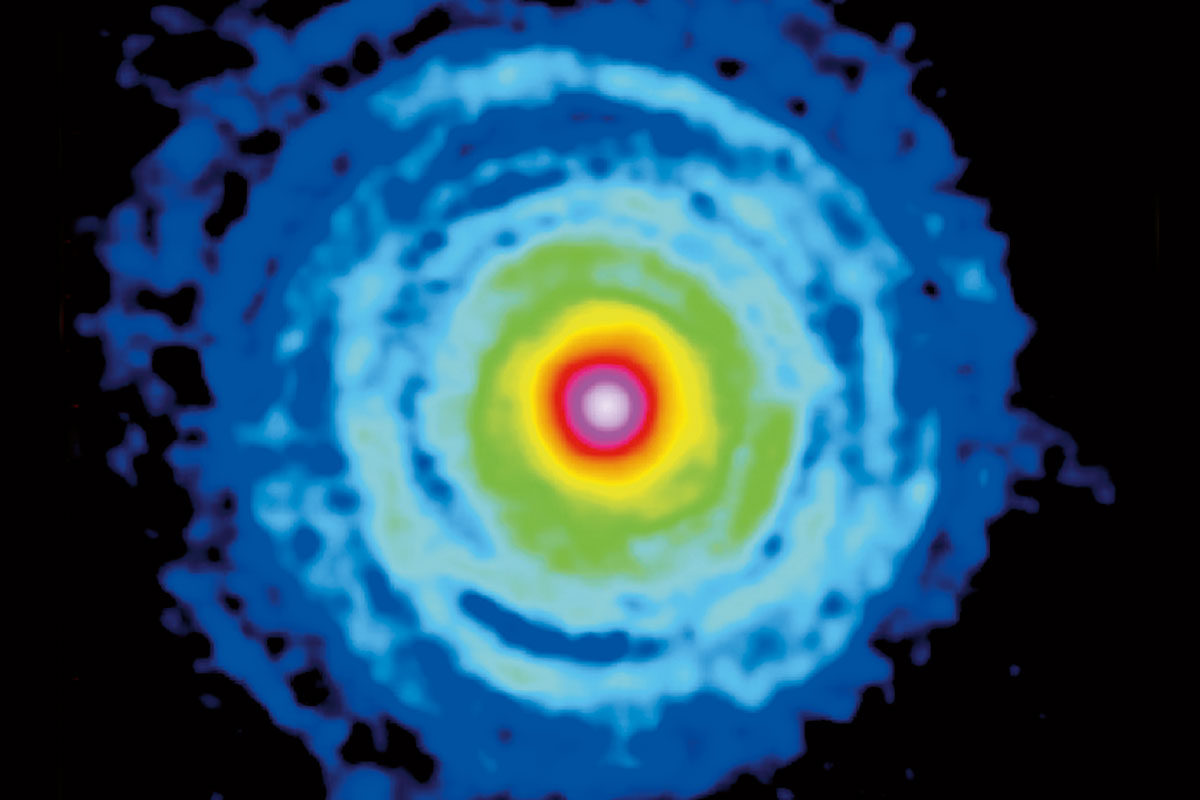

Composition from IRAM 30m radio telescope data, showing matter around the star CW Leonis (IRC+10216). As can be observed, the external, cooler layers of the star (in dark blue) are fragmented, and a 2015 study proposed that the mass of the star might be in the process of being devoured by a companion star. / J. Cernicharo, N. Marcelino, M. Agundez, & M. Guelin

Looking up at the sky during a dark and clear night is a luxury not everyone can enjoy. Mainly because we have so much artificial lighting that stargazing is becoming a rare treat that requires going out of cities and towns. Going on a stargazing walk might seem romantic, but might it be the case that over time – and having so little of it – we have forgotten this humbling experience? Does it not make us wonder anymore?

I do not have an answer, of course. I can imagine a dystopian world in which we read books and study wavelengths setting aside the original fascination: looking up at the sky.

Looking up at the sky was the driving force. Being able to explain what we saw was the next challenge. And we went from making up those explanations to (fortunately) studying them. Now we know we are part of a star system composed of a series of rocky and gaseous planets; that we are in one of the arms of a spiral galaxy; that there is a black hole – one of the tame ones – at the centre of our galaxy, the Milky Way; and that there are many more galaxies like ours. But not only that: we also know that those other galaxies have their own solar systems, other stars like our Sun with planets being born around them; we know how some stars are born and die; we have discovered worlds similar to ours… And now we are quite certain of our expiration date.

Our ability to observe the sky started with the obvious (what our eyes could see) and, in a very short time, turned to those other light ranges that were beyond our reach. The electromagnetic spectrum broke open and gave us the option to seek further explanations for more or the mysteries around us. One of them was, for example, that of dark clouds, mistaken at first as «holes» in the sky, apparently empty areas. But they were definitely not empty. They were, as I was saying, opaque clouds which, due to our primitive tools, prevented us from seeing what was actually happening within. Mulling it over, the enquiring minds of research teams found the answer. Those areas had to be studied in other wavelengths like infrared, which «bypassed» the cosmic dust that made those clouds opaque. And they continued with the rest of the spectrum, including radio waves. What for? Well, to study the coldest stuff, the least energetic objects: the dance of molecules and their ball of atoms. That is how, back in the 1940s, the bases for what we now know as astrochemistry (or laboratory astrophysics) were set.

«Looking up at the sky was the driving force. Being able to explain what we saw was the next challenge»

This discipline, drawing from astrophysics and chemistry, studies the molecules in the universe. This is not easy because they tend to huddle up in scores and make it very difficult to identify them (like finding someone at a crowded concert looking from an elevated position… well, much more complex, actually, but you get the gist).

Astrochemistry studies their abundance and composition and posits potential chemical pathways that might have led to the presence of such molecules in a particular environment. But they do not just look up at the sky: to make sure that what we propose is possible, we try to reproduce that chemical «walk» in a laboratory and check whether our hypothesis coincides with the results of experiments. Only then can we be sure that what we deduced is a real possibility. Laboratory astrophysics helps us understand what happened that allowed us to be here today. Thus closes a circle (or, rather, a loop): looking up at the sky to study the chemistry of the cosmos on Earth and try to understand the universe.

Please keep looking up at the sky once in a while.