The most accurate image of Arrokoth, taken on 1 January 2019 by the New Horizons probe / NASA, Johns Hopkins University APL, Southwest Research Institute, NOAO

2006 was definitely a very important year for Pluto. We all remember that, in August of that year, thousands of astronomers participating in the General Assembly of the International Astronomical Union held in Prague decided to give a more precise definition of what a planet in the Solar System should be. This definition removed Pluto from the list of nine planets that orbit the Sun. Pluto thus lost the category it had held since its discovery in 1930 and became the archetype of a dwarf planet. Perhaps not so many people will remember that on 19 January 2006 the New Horizons probe was launched by NASA from Cape Canaveral, with the help of an Atlas V rocket.

The main objective of the probe was to study the Pluto-Charon system. The latter is a satellite of the former, but its diameter is about half the diameter of Pluto, so we can actually interpret this system as a binary planet, with both bodies orbiting around their common centre of mass, the barycentre, which in this case is a point outside both celestial bodies.

New Horizons reached its destination in 2015, after passing near Jupiter and taking advantage of the opportunity to send very interesting information to Earth about the atmosphere of the largest planet in the Solar System. The main reason for this was to carry out a gravitational assistance manoeuvre that would allow it to considerably increase its speed towards its final destination.

On arrival, New Horizons discovered a faint atmosphere on Pluto, produced by the sublimation of the icy surface material, which also contained organic particles. It found a gigantic nitrogen ice glacier in the area known as Sputnik Planum, on which mountains of water ice several kilometres high float like icebergs. Regarding Charon, it showed us a surface dominated by water ice, which is geologically young – i.e., it has few craters – with canyons between 5 and 10 kilometres deep, completely crossing the equatorial zone of the body. An enigmatic dark spot, known as Mordor Macula, near the North Pole, also surprised us.

But New Horizons continued its trip to the confines of the Solar System, moving away from Pluto to get a closer look at other objects in the Kuiper Belt, a region that begins just beyond Neptune’s orbit and extends to a distance equivalent to 50 times the average distance from the Earth to the Sun. The Kuiper belt is similar to the asteroid belt that lies between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter, but about twenty times wider and possibly a hundred times more massive. Most of the objects that populate it are made of more volatile materials which astronomers call ices (methane, ammonia, water, etc.). Three of the so-called dwarf planets are found in the Kuiper belt: Pluto, Haumea and Makemake.

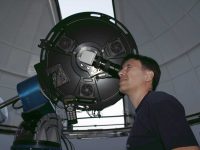

The first object in the Kuiper belt visited by New Horizons after leaving Pluto was provisionally named Ultima Thule and has recently been renamed Arrokoth. It is only 35 km in diameter and was discovered by the Hubble Space Telescope in 2014. On 1 January 2019, New Horizons passed just 3,536 km from this small body in the Kuiper belt and analysed it as it flew by, sending images and data of the most distant celestial body that any space probe has ever explored. It was more than 6.6 billion kilometres from Earth.

The image did not disappoint. With a resolution of 33 meters per pixel, it shows us a binary contact object formed by two lobes, one of them quite flattened, with hardly any craters. This distant trans-Neptunian object has remained potentially unchanged since the two lobes merged shortly after the formation of the Solar System 4.6 billion years ago. A pristine picture of our origins.