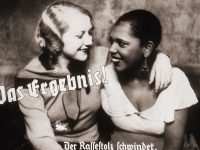

Working on Nazism and its relationship with science and scientists is undoubtedly one of the most interesting areas of research for historians studying Germany, the elites, and scientists.

Indeed, for a long time «Nazi science» was considered the work of a minority of sages on the edge of madness and perversion, committed to political atrocities, without it affecting the rest of the German scientific landscape. But these assertions were brought down by numerous studies. On the one hand, only a negligible part of scientists refused to work for Nazi Germany: less than 1 % of university graduates resigned after the Machtergreifung1, meaning that 99 % of university professors continued working in Nazified institutions. Anthropologists, physicians, historians, sociologists, linguists, and geographers benefited from research programmes that turned their disciplines into «legitimising sciences»2, i.e., «combatant sciences». The more or less certified commitment of many prominent scientific figures, such as the psychiatrist Johann Asperger or the physicist Werner Heisenberg, is not that surprising when we contextualise it with the broader history of elites.

«National Socialism came to power by following the electoral strategy of a popular party, but with the support of extremely well-educated militant elites»

The scientific field was no exception in 1930s Germany: 1990s social history proved that the elites’ adherence to the National Socialist party and the Nazi racial determinism was connected to the great appeal of Nazi ideology’s appeasing belief system, but also to the existence of elitist organisations that allowed these specific circles to find a place for entre-soi3. socialisation and self-preservation. This is one of the great paradoxes of 1990s historiography. After mercilessly but fairly responding to the problems in Hannah Arendt’s work regarding Nazi «totalitarianism»4, social historiography tended to quietly confirm that National Socialism came to power by following the electoral strategy of a popular party, but with the support of extremely well-educated militant elites. That is how the party adapted to the most significant characteristic of totalitarian regimes. In the eyes of German philosophy, this structure was considered an unprecedented alliance between the masses and the elite.

Deep down, how else can we define institutions such as the SS, the Ahnenerbe, or the Sicherheitsdienst? Or the Volkswissenschaftliche Arbeitskreis (“Population Ethnoscience Work Circle”), which grouped university specialists and SS officers to study the populations of some Eastern European territories with the aim to legitimise their conquest? Nazi science is not just a collection of skulls from exterminated Jewish citizens, nor is it a group of experts condemning entire populations like the Krymchak – a Jewish ethnic group from the Caucasus –, or indulgent speeches at university ceremonies, or inhumane medical experiments like submerging Soviet officers into freezing water in concentration camps. Nazi science is equivalent to daily acceptance, to the slow and thorough penetration of resignation and the commitment to an ideology that permeates everything adorned as a hopeful utopia, a great addictive toxin to which the cultural elites are particularly sensitive.

1 A term referring to the National Socialist takeover of the German

government. (Go back)

2 Schöttler, P. (1997). Geschichtsschreibung als Legitimationswissenschaft, 1918-1945. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp. (Go back)

3 For the definition of the entre-soi concept (“among peers”), see Héritier, F. (1990). Les matrices de l’intolérance et de la violence. In F. Héritier (Dir.), De la violence II (p. 321–343). Paris: Odile Jacob. (Go back)

4 Arendt, H. (1973). The origins of totalitarianism. Houghton: Mifflin Harcourt. (Go back)