ABSTRACT

Social and cultural anthropology has studied reproduction from numerous viewpoints – kinship, symbolism, feminism, health – highlighting its scope and its social, constructed and central role to the preservation of any society. Based on this view, the authors put forward certain hypotheses by which to understand reproduction as an issue uniting women’s lives today, and which should be an object of study relevant to science.

Keywords: women, reproduction, anthropology, gender.

This article approaches one of the issues posing a challenge to all women today: reproduction. The topic is dealt with from the anthropological perspective. To start with, we must clarify what we mean by the term reproduction, because, as Olivia Harris and Kate Young (1981; in Comas, 1998) rightly state, this concept encompasses different dimensions that, albeit related, are dissimilar and have very different meanings. In this respect, we must distinguish between: biological or human reproduction; reproduction of labour; and, social reproduction. Let us look at each of them briefly: the first, biological reproduction or procreation, refers to increasing the number of individuals in a population; the second involves reproduction of the sexual division of labour, as different activities are assigned to men and women, thereby perpetuating differences. And the third, social or systemic reproduction, concerns transmitting and giving continuity to a given social system by reproducing ideas, values, norms, and also establishing a social order in terms of family relationships, economy and other areas.

«A proper approach to reproduction is essential if we are to effectively promote the advancement of women in all social areas»

Considering these dimensions of reproduction leads us to wonder about their dynamics and current related issues, which have a special impact on the lives of women. It is sufficient to give the example of women working in science, for whom the demands and requirements of biological reproduction interfere with furthering their academic and professional careers. Consequently they are forced to adapt the latter to the former, in an attempt to make them compatible, if not they must give up one for the other. We believe that a proper approach to this complexly interwoven issue –reproduction– is essential if we are to effectively promote the advancement of women in all social areas; furthermore, knowledge of the complex reproduction phenomenon should bring to light the inequalities still at large in current society. In short, we propose to study a subject that specifically affects the status of women, and men too, which therefore deserves the effort and time required to stop and rethink.

To this end, in the first part of this article we will review some of the contributions made by the fields of anthropology dealing with reproduction. Then we will go on to discuss our arguments regarding the central role reproduction still holds in the lives of women today, providing several examples.

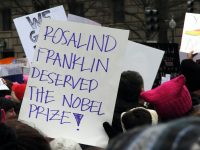

Nowadays women are free to choose what procreation option suits their own situations. Mothers by choice, formerly known as «single mothers» are a clear example of this». / SINC

Approaches to reproduction

Within the field of anthropology, we find early exploration of the issue of biological reproduction. Some classic ethnographies, such as Bronislaw Malinowski and Ashley Montagu (in Browner and Sargent, 1990: 221), describe the most important socio-cultural aspects, as for instance norms, values and taboos surrounding menstruation, pregnancy, childbirth and the period after giving birth. In a similar vein, although more closely related to Spanish territory, noteworthy is the data collected in the Ateneo Survey of 1901-1902 (Limón and Castellote, 1980) on customs related to certain phases in the life cycle: birth, marriage and death. The aforementioned survey also reflected the beliefs, superstitions and even the «remedies» that social groups entertained surrounding the entire pregnancy cycle, and which reflect the roles, rules and expectations established for women and men at this stage of biological reproduction. This is a crucial stage in a person’s life and in terms of social order, because, as Arnold Van Gennep stated, the birth of one’s child should be seen as a «rite of passage», leading to a change in the parents’ status (female to mother and male to father), while regenerating kinship ties.

«Women today have greater freedom of choice, and can choose from among various procreation options; although there have always been strategies to choose whether or not to become a mother»

Since the seventies, numerous ethnographies have arisen (Blázquez, 2005), aiming to show how procreation, albeit a biological process, cannot be understood outside social relationships nor the significance and implications posed for each social group within each historical context. Not only does reproduction bridge the gap between the biological and the cultural, but also articulates gender roles –regarding femininity and motherhood; masculinity and fatherhood– within a socio-political and ideological system (Browner and Sargent, 1990). These studies introduce an analysis from the viewpoints of feminism and social class, linking biological reproduction with other dimensions, such as gender-based division of labour and the perpetuation of a patriarchal and capitalist social system.

The interrelationships between the two levels (biological and socio-cultural) indicate that the female body is not just an entity consisting of biological matter, but rather it concerns well defined conceptualisations, in other words, specific ways of living and caring, which rest, in turn, on political and socio-cultural foundations. Some ethnographic studies on the subject focusing on fertility, the process of giving birth, pregnancy, lactation… show how all these female bodily processes are socially and culturally regulated (from biomedical care models to rituals and taboos).

«Procreation, albeit a biological process, cannot be understood outside social relationships nor the significance and implications posed for each social group within each historical context»

In Spain, anthropological studies on health have been carried out regarding the ideas, norms and roles assigned to women with respect to procreation. Such examples come mainly from the health ambit –which could be defined as «bio-power» in terms of Foucault– establishing the types of norms and forms of subjectivity that, among other things, place maternity and childcare at the heart of a women’s life, as suggested by Mari Luz Esteban et al. (2010).

Other fields, like the anthropology of kinship –concerned with the development of ideas, representations, norms and practices surrounding reproductive processes, bonding and parenting (Fons et al., 2010)–, analyse the current changes in family structure due to migration, adoption and new reproductive technologies, revealing new meanings and concepts.

These specialised fields of anthropology have developed independently and within different theoretical frameworks; however, on coinciding in a common object of study, they have all made important contributions to revealing how reproduction affects women’s lives. Below, from this broad and complex vision of reproduction, we would like to tackle some questions on how women’s lives are affected.

Ana Ponce & Ivo Rovira

Perspectives emphasising the central role of reproduction in women’s lives

The analysis given is product of data gathered during our research, focusing on women in our current context of Spain in the early years of this new millennium, although similarities may be found with women elsewhere and at other historical moments.

Our starting point is based on the premise that, sometime in their lives, all women have the possibility of reproducing. Reproduction is understood in the triple sense posed at the beginning: biological reproduction, reproduction of labour and social reproduction. Let us look at each in turn.

Regarding biological reproduction, with all the implications of procreation, women must inevitably confront the decision to become mothers or not. In this regard, the key factor is age and, more specifically, the upper age limit contemplated as being apt for gestation. This is because a woman’s age –be it 35, 40 or above– can be considered a marker or warning signal, reminding her of the risks pregnancy may pose and, therefore, the need to decide without further delay. One of the most recent changes is that motherhood is now considered an option of choice, one of the most perceptible examples being the formerly known «single mothers», now known as «mothers by choice» (Rivas et al., 2011). This change reflects a major shift in the social, cultural and political institutions that recognise different concepts of motherhood, as well as different procreation means –no longer limited to biological reproduction– and the difference in the age at which a woman can become a mother and the considerable diversity in current family structure. Consequently, women today have a wider range and greater freedom of choice, and can choose from among various procreation options; although there may always have been strategies to choose whether or not to become a mother, which may or may not have been visible, recognised or sanctioned.

Although women may choose to procreate or not, social interpretations and meanings of corporeality still bind her to this possibility: the opportunity to be a mother, with the subsequent implications of pregnancy, giving birth and breastfeeding. It is noteworthy that a negative decision in this respect does not terminate the social significance or visions and values related to her body. For example, phenomena and dimensions such as sexuality, menstruation, certain diseases like breast cancer or menopause, are interpreted by women themselves and by society as a whole, from cultural assumptions based on the criterion of accepting or relinquishing procreation: that is, regarding the «use» that can be made of one’s body or not.

«As women of science – like many others – our own lives and agendas have been confronted by the issue of being or not being mothers»

The second dimension of reproduction discussed –namely that related to perpetuating a type of labour system– has not changed. Women remain fundamentally, and often solely, responsible for domestic chores and housework. Available data show that, although women have joined the paid labour force (albeit suffering prejudice and comparative grievance), this has not been accompanied by an increase in men’s participation in tasks related to reproduction and childcare. Women continue to be –especially in these present times when the welfare state is being dismantled– the main providers of domestic work, childcare and parenting. Data show that there are some differences in these tasks due to differences in social class, age and ethnicity of the women performing them, but there is an absence of males performing these tasks (García Calvente et al., 2004). In this respect, it is worth noting that the preferred professional profile of a caregiver is an unmarried woman, as her marital status does not interfere with her childcare tasks. Moreover, reconciling work and family life gives rise to a «daily double-shift», which still wears a woman’s face. Although some women nowadays, who have a profession and belong to certain social classes and groups, have known how to and been able to break free of the procreation mandate, or subject it to free will, reproduction of labour continues to be ingrained in their lives, and they feel responsible for the care of others or become responsible for such care-giving in one way or another.

The third dimension of reproduction, namely the social or systemic, shapes, organises and gives meaning to the others, and defines social order. In this respect, the contributions made by Gayle Rubin (1996) are indispensable. This author highlights how these two dimensions, those relating to procreation and the sexual division of labour, and their inevitable consequences, must be ordered by a sex/gender system. That is, society discriminates against individuals based on their biological sexuality and sexual order, establishing a net differentiation system. This system is created within political and economic conditions, which give a meaning to the sexes, procreation and sexuality, constituting a true sex-related political economy.

Increasingly, women try to combine their interests with the roles society has given them to play for years. A never-ending fight to show they are both capable and complete women, casting their motherhood aside. / Miguel Lorenzo

Women have internalised the importance of respecting social order, defend it and transmit it. Paradoxically, this very system has placed the responsibility of self-reproduction on women. To this end, the mechanisms controlling women are far-reaching and diverse, but all have in common the aim to promote and ensure the continuity of this system of sex-related political economy. In her study of the institution of heterosexuality, Adrienne Rich posits that means adopted to dominate women range from property access to controlling their minds and bodies (1980; in Pichardo Galán, 2009). Therefore, the control of women’s bodies, for example by maintaining certain reproduction-related cultural visions –essentialist, biologicist, asocial, reductionist– would serve to perpetuate and spread this social order. In our research work carried out in the health field, we have shown how women are «domesticated» through the imposition of certain patterns on their bodies, to ensure procreation, reproduction of the labour system, and thereby reproduction of the whole social system (Montes, 2007). Therefore, a system, with this composition, requires reproduction (in all and each of its dimensions) to continue to be lodged at the heart of a woman’s life.

In a post-capitalist society like ours, we have a set script establishing that the lives of women should be programmed for reproduction. This happens inexorably, even though there are variations on this script, and women can take up different positions in order to answer, confront and face this issue, either individually and as a group. Again, we argue that while some women have been able to choose to «free» themselves from biological procreation, domestic work and particularly the care of others, it has not led to a change in the established order. Their acts of emancipation are necessary, but not sufficient to subvert our current sex/gender system. It is noteworthy that women, in all facets of their lives, even in the workplace, are called upon to take care of the reproduction of the group, and by extension of the affective, care and maintenance of social relationships. Thus, for example, «mentoring» by academic women has been described as a form of «mothering» and care, especially in the case of those who could not be mothers; but when men are mentors, definitions are not linked with parenting or cultural role models.

Conclusions

Here, we have endeavoured to show that if we consider reproduction as the broad concept proposed by anthropology, then reproduction forms a part of our social existence, which is inextricably linked –for the time being– to the lives of women. This meaning of reproduction is very different from that referring to men and, while it may take on wide variety, it inevitably runs into monotony. Anthropology helps us to observe how people run their lives and understand the mechanisms of the same within the social whole. Seen from this perspective, we are impelled to state that the current situation of women is not «natural», but rather responds to a social order, against which many bring to bear resistance and struggle to articulate their interests and their projects within a cultural legacy they have inherited. On a more personal note, as women of science –like many others– our own lives and agendas have been confronted by the issue of being or not being a mother; and we are also urged to take care of reproduction, domesticity, care-giving. We are fully aware that women have to invent and develop strategies to mitigate the costs and consequences of accepting, but above all of forgoing caring, maternity and parenting, a destiny forced upon us by the cultural imperative.

Therefore, we shall end by stating that one of the key issues distinguishing men and women, establishing sexual differences in our society today, is that women are the ones caught up in this debate, in this plot, in this challenge, wondering whether to be mothers, caregivers, responsible for reproduction, and if so, how.

References

Blázquez, M., 2005. «Aproximación a la Antropología de la Reproducción». Revista AIBR, 42: July-August.

Browner, C. & C. Sargent, 1990. «Anthropology and Studies of Human Reproduction». In Sargent, C.& T. Johnson. Medical Anthropology: Contemporary Theory and Method. Praeger. New York.

Comas, D., 1998. Antropología económica. Ariel. Barcelona.

Esteban, M. L.; Comelles, J. M. & C. Diez Mintegui, 2010. Antropología, género, salud y atención. Bellaterra. Barcelona.

Fons, V.; Piella, A. & M. Valdés, 2010. Procreación, crianza y género. Promociones y Publicaciones Universitarias. Barcelona.

García Calvente, M. M.; Mateo Rodríguez, I. & G. Maroto-Navarro, 2004. «El impacto de cuidar en la salud y la calidad de vida de las mujeres». Gaceta Sanitaria, 18(2): 83-92.

Limón, A. & E. Castellote, 1980. «La medicina popular en torno al embarazo y parto a principios de siglo». In M. Kenny y J. De Miguel. Antropología médica en España. Anagrama. Barcelona.

Montes, M. J., 2007. Las culturas del nacimiento: Representaciones y prácticas de las mujeres gestantes, comadronas y médicos. Tesi doctoral en Antropologia Social i Cultural. Universidad Rovira i Virgili. Tarragona. Available at: <http://www.tdx.cat>.

Pichardo Galán, J. I., 2009. Relaciones homosexuales y nuevos modelos de familia. Bellaterra. Barcelona.

Rivas, A. M.; Jociles, M. I. & B. Moncó, 2011. «Las madres solteras por elección ¿ciudadana de primera y madres de segunda?». Revista Internacional de Sociología, 69(1): 121-142. DOI: 10.3989/ris.2009.06.27.

Rubin, G., 1996. «El tráfico de mujeres: notas sobre la “economía política” del sexo». In: Lamas, M., (comp.). El género: la construcción cultural de la diferencia sexual. UNAM. Mexico DF.