This article addresses the advent of the theory and treatment of chronic pain from the second half of the nineteenth century until the mid-twentieth century. It would appear that pain medication emerged from the confluence of practices related to treating patients with terminal diseases and those suffering from incurable pain. Although the distinction between acute pain and chronic pain is important, this distinction alone does not explain the importance attached to a condition that is an anomaly within the theoretical framework while being perceived vital within the cultural context.

«Discomfort that starts but does not stop makes one question the rationality of a system that has strived to explain the experience of illness for centuries»

In a paper published in December 1832, Professor Elliotson described a case of neuralgia resistant to all forms of treatment. The record alternated clinical specification with its inability to produce not only a cure but even temporary relief of the symptoms (Turnbull, 1837). Pain appeared in the legs, arms and wrists, as well as on the right side of the face, in the submaxillary nerve. The patient had been in this situation for some years, but the illness had started even earlier. At first, an agonising, excruciating pain, like a blade cutting his finger, concentrated on the index finger of his left hand. The slightest touch caused a very violent reaction, like an electric shock. The despair was such that he reached the point of biting all his nails on his healthy hand as if with this gesture he could make the extreme suffering of the other disappear. The doctor, who said he did not know the immediate cause of the pain, in this case made no reference to hypnotism or mesmerisation. By contrast, he tried to build a diagnosis based on the negative features resulting from patient exploration: there was no inflammation, no reddening, nor temperature increase. «There is nothing at all –he said– except the agonising pain».

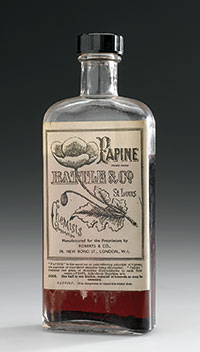

Empty bottle of morphine used for pain in the nineteenth century. The name refers to Morpheus, the god of dreams in ancient Greece. / © Science Museum, London

Elliotson started by administering iron carbonate combined with a quarter of morphine muriate. A solution of potassium cyanide was also applied to the finger. In the absence of improvement, the dose was increased to one grain of morphine every night. He then dispensed with the iron and introduced strychnine, first locally and then orally. At the same time, he increased the daily dose of morphine, but the patient’s general health began to deteriorate without any significant change resulting. He then began treatment with arsenic. When the amount of morphine had reached eight grains per day, the agony was such that the patient begged for ever higher doses of the opioid. Otherwise, he said, he could barely exist (Turnbull, 1837). Extracts of stramonium or belladonna were also ineffective. Amputation of the finger insistently requested by the patient would not solve the problem, because according to Elliotson, it was a «chronic illness, connected with some organic disease impossible to detect not even after death, as occurs with epilepsy or paralysis» (Turnbull, 1837).

Just as pain without injury suggests the presence of a psychological dysfunction that can be characterised as delusional, chronic pain also creates distrust. The presence of discomfort that starts but does not cease makes one question the rationality of a system that has strived to explain the experience of illness for centuries. Faced with the every-day experience of pain, anaesthesiologists, surgeons, psychiatrists and health care professionals always understood this form of anxiety as an exception to illness, as an anomaly that occurred in a transient state in itself. Not only was it rare, but clearly abnormal: a form of suffering that contradicted established protocols that, based on the symptom, would lead to the cure (or to death) by means of treatment.

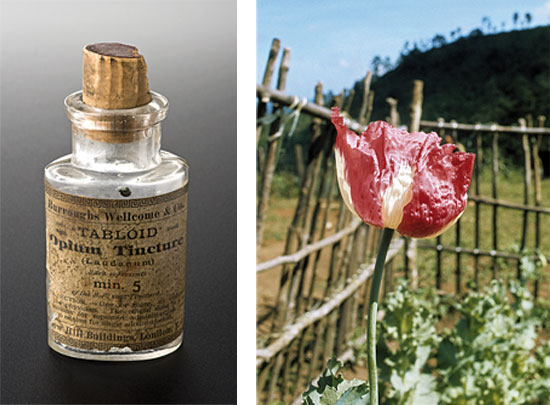

© Science Museum, Londres. Opium flower cultivated in northeast Thailand in the early seventies. Since the late nineteenth century, doctors such as Herbert Snow promoted the widespread use of opium in the treatment of incurable cancer based on its analgesic properties. Top, left, a bottle of tincture of opium, from the British pharmaceutical company Burroughs Wellcome & Co., used between 1880 and 1940. / © UN Photo/UNPDAC/NJ

For a long time, the only way to ultimately escape this endless torture was death. However, according to Dr. Falret, who wrote a book on the subject in the early nineteenth century, physical pain is endured with more resignation than moral suffering; his book contains many examples of human beings who had taken their own lives as a result of prolonged suffering (Falret, 1822). One woman, who felt as if she was being bitten by dogs devouring her flesh, strangled herself with a rope tied to the ceiling. Another, who suffered from rheumatism and could not kill herself on her own, constantly pleaded with her friends to put an end to her agony. A third who suffered from uterine cancer poisoned herself with opium grains in the Salpêtriere hospital; and there are many other cases. In dozens of cases studied by this expert on hypochondria, what actually led men and women to jeopardize their existence was not indifference or weariness towards life, but «the real or imaginary pain, having destroyed the harmony of their capabilities and having brought disorder to their wills, imposed on them the sacrifice of the most precious of possessions» (Falret, 1822).

«Surgeons and neurologists always interpreted the history of pain as the necessary culmination of a longer historical process that involved a humanitarian concern for pain and death»

Chronic pain

The onset of pain as a focus of medical practice, one targeted by the pharmaceutical industry and the market, is a twentieth century phenomenon. Only then did the so-called faithful friend, the cry of life, God’s punishment, Christ’s weapon, the punitive instrument, the educational rule become the subject of research programmes and of institutional care. In our time, although still limited, the pain experience has achieved corporate recognition and become a field of scientific development. Just looking at the growth of specialised palliative care units during the last sixty years shows us the extent to which pain-specific instruments, associations and institutions already exist (Baszanger, 1998; Beinart, 1988; Szabo, 2009). In 1967, while the pictures and bodies from the Vietnam War reached the West, the clinical and academic interest in this new order led to the founding of the Intractable Pain Society. The journal entitled Pain, part of the International Association for the Study of Pain, was first published in 1974 (Natas, 1996). For those involved, the emergence of this new branch of medicine seemed to be the culmination of a process, the last chapter in a narrative sequence that had led humans from the logic of resignation to the technology of resistance. After the «abolition» of surgical suffering in the mid-nineteenth century and the massive introduction of analgesics in the consumer culture of the twentieth century, we were still to find an effective treatment to combat suffering associated with incurable or terminal diseases, but also for what is today called fibromyalgia, rheumatoid arthritis, facial neuralgia or post-traumatic syndromes, i.e., different varieties of prolonged or intractable physical agony. Surgeons and neurologists always interpreted the history of pain in this way: the result of a proliferation of abnormal phenomena that the inherited theoretical framework seemed unable to explain but, also, as the necessary culmination of a longer historical process that involved a humanitarian concern for pain and death.

A bottle of Papine, trade name for an analgesic of the opiate family in the early twentieth century. The illustration on the label directly refers to the opium poppy flower (Papaver somniferum). / © Science Museum, Londres

Often, this «humanitarian concern» called for the use of opioids in terminally ill patients, promoting a policy (not always accepted socially) to make available to patients the tools and chemicals necessary to reduce their suffering (Clark, 2003). In 1890, the physician Herbert Snow promoted the widespread use of opium in the treatment of incurable cancers (Snow, 1890). Three years earlier, William Munk had also begun his pioneering treatise on euthanasia, calling for the medical supervision of death; this also included providing patients with the means required to prevent their suffering. This English physician and historian believed that opium should be used both to relieve pain and the feeling of fatigue and depression, exhaustion and anxiety, which are sometimes present during that last journey (Munk, 1887).1

Almost one hundred years later, in a 1982 publication, Patrick D. Wall and Ronald Melzack wrote an account of the same pain that had tormented the patient described by Elliotson and other thousands of people before and after him. This text was based on an initial distinction between acute pain, which since early times had been one of the visible signs of disease, and chronic pain, which they described as a disease in itself or, more precisely, as a group of syndromes. In the 1980s, many members of the scientific community –physiologists, neurologists and anaesthesiologists– recognised that while the former, being a sharp pain, could represent a degree of utility –at least making it possible to anticipate the presence of an underlying condition– the latter (chronic pain) could only be interpreted as a disorder causing patients, their families and society –as a whole– a lot of suffering, while its presence could not be justified by any clinical reasoning whatsoever (Bonica, 1976).

The French surgeon René Leriche was known for rejecting the concept of pain as a necessary evil of disease. / © U. S. National Library of Medicine

Although this new disease began to quickly fill up bookshelves, with its divisions and subdivisions of harmful syndromes, the first taxonomies were of a dichotomous nature. Medicine began to distinguish between useful pain and useless suffering, between laboratory pain and clinical suffering, between peripheral pain and central pain, between pain in the limbs and pain of the viscera. Some other conditions, such as the suffering associated with incurable diseases, took on a new light. The researcher Marcia Meldrum claims that from the mid-nineteenth century to the present day pain has become the subject of three related medical discourses: the symptomatic relief of acute pain, treatment of severe pain in terminally ill patients and chronic pain treatment in cases of migraine, rheumatoid arthritis, trigeminal neuralgia and other syndromes of a non-specific nature (Meldrum, 2003; on the development of aspirin, see Jeffreys, 2004). The key word in this list is association since –although research lines developed independently– pain medication always developed in their areas of confluence. The terms acute, chronic, terminal and nonspecific disease can only be understood within the context of the fragmentation of an experience, effectively leading to the multiplication of names and theories and to the formation of a new scientific community and an institutionalised form of treatment revolving around a new group of people: patients in pain.2

Although there was already a distinction between acute and chronic pain in romantic physiology, it only appeared explicitly in the second half of the twentieth century. The International Association for the Study of Pain, founded in 1973, depended so much on this distinction between transient and chronic pain that when the concept of pain reached full recognition in the field of clinical research, it did not do so as a single object, but as several.3 Its emergence coincided with the partial dissolution of what had hitherto been called by that name. Human suffering is dissolved into a typology of intermediate states or harmful syndromes (Wall and Melzack, 1996).

Some, such as causalgia, the phantom limb or trigeminal neuralgia, were old acquaintances of medicine, but not always known by those names. Many others, however, appeared as a result of the new subdivisions. In 1986, the Association for the Study of Pain proposed the first major classification of so-called «chronic pain syndromes» (Merskey, 1986). Fibrositis, the burning mouth syndrome, or tendinitis began to coexist with the diversification of migraine or persistent back pain.

The world was full of newcomers: allodynia, painful anaesthesiam dysesthesia, hyperalgesia, hisperaesthesia, paraesthesia, neuritis or peripheral pain described realities that until then had only existed in literary papers, hidden by the incomplete stories, sometimes incredible, of affected human beings. Although the diagnostic value of pain was not in question, suffering (chronic or terminal) was dissolved in a family of experiences that exceeded by far, if not contradicted, the theoretical elements on which the relationship between injury and pain had been built.

«In contrast to scientific medicine, this new clinical practice should not seek the disease in the patient’s body, but rather understand each patient in the context of their disease»

That was always the first problem: «Doctors are willing to quickly admit that pain is a defensive reaction, a fortunate warning that alerts us to the dangers of disease. But what is a defensive reaction? Defence against whom? Against what? Against cancer, which so often causes symptoms when it is too late? Against heart disease, which develops in silence?». This is what the surgeon René Leriche (1949) meant when he repudiated the false conception that the presence of pain was associated with «necessary discomfort» and that –particularly in France– it had been the basis of physiological research on pain since the early nineteenth century. Semiotics of suffering, the translation of expressive gestures into clinical signs, had made it possible, among other things, to talk about animal suffering or pain in childhood, but was always unable to explain what warning was provided by trigeminal neuralgia or how the suffering typical of carcinoma could actually protect someone. Indeed, when pain did not fall into any category or correspond to any treatment it lost significance, not only in the (obvious) sense that it could no longer be interpreted as the sign of a hidden lesion, but also to the extent that science no longer had the necessary elements to visualise it.

The same occurred with cancer. As the disease multiplied into a host of varieties, medical discourse could no longer address the causes underlying the disease as such, but rather shed light on its progression and in many cases, searched for palliative treatment (Stoddard Holmes, 2003). On the one hand, the same disease was acquiring a number of names which, like epithelioma, blastoma, rodent ulcer, fibroma or lympho-carcinoma, coexisted with more primary classifications. In a very general sense, tumours appeared to be divided into benign tumours and malignant tumours, as well as painful and silent tumours (Snow, 1893; Bland-Sutton, 1903). This latter division, though extremely simple, had a great significance, for while some tumours developed without pain or with only slight discomfort, many others –even of the same type– produced extreme and prolonged suffering (Fell, 1857). The discovery of long-term symptomless illnesses, on the one hand, and of the proliferation of symptoms (also long-term) that did not correspond to any «curable» disease, on the other, were two sides of the same coin.

The triple concealment

Both «disease without symptoms» and «symptoms without disease» underwent a triple process of concealment related to experimental approaches and clinical practices. For one thing, physiology manuals hardly addressed visceral pain, i.e., those which did not easily comply with laboratory practices and their mechanical processes of objectification and experimental manipulation (Ryle, 1948). Secondly, clinical medicine and its efforts to objectify disease led it to inevitably ignore or conceal the human factor. Rather than this disregard for the patient in nineteenth-century medical cosmology (Jewson, 1979), hospital medicine should be concerned with finding a connection between the lesion and the illness, based on close examination, comprehensive questioning and a detailed description of the experiments that nature itself operated spontaneously in the human body (Ryle, 1935). In contrast to scientific medicine, this new clinical practice should not seek the disease in the patient’s body, but rather understand each patient in the context of their disease. For healthcare professionals, the physician’s task was to cure when possible, and to alleviate suffering when it was not.

Last but not least, the uneven distribution of illness among different population sectors also led entire human groups to social invisibility and clinical oblivion. This latter form of invisibility affects not only the history of medicine, but is a far-reaching phenomenon related to the cultural development of a disease, or of a group of them, which did not affect all citizens in the same way, having special impact on the most vulnerable population sectors.

Although it can be said almost tautologically that all diseases are man-made, chronic diseases owe a great deal to their social context; the mere recurrence of symptoms does not determine a clinical condition. Indeed, the history of medicine has given us examples of diseases that are currently considered non-existent, whose symptoms resemble some of our modern medical conditions. Let us consider neurasthenia for instance. The symptoms of this debilitating condition, so fashionable in the second half of the nineteenth century, bear a striking similarity to some manifestations of depression, stress or, more specifically, the so-called chronic fatigue syndrome of contemporary societies.4 The same could be said of hysteria, considered as an epidemic by the psychiatrists of the mid-nineteenth century.

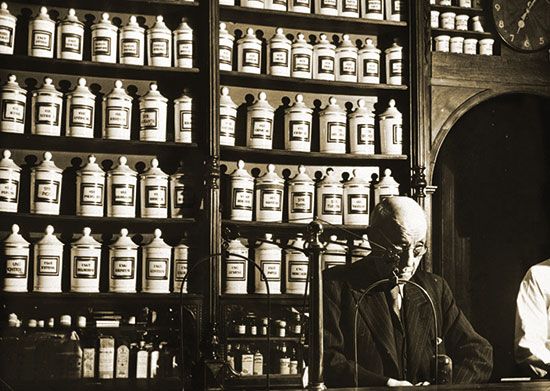

A classic late nineteenth century pharmacy. Pain as an object of the pharmaceutical industry did not emerge until the twentieth century, at the same time as in the medical and social fields. / © WHO

Chronic pain plays a major role in many intractable or incurable conditions. Likewise, it appears repeatedly in long-term nerve diseases, whether these diseases have an organic or a psychological origin. This historical evidence suggests that the absence or presence of the term «chronic pain» does not alone clarify the nature of the disease. The problem does not depend on a name –which did not achieve widespread use until the 70s– but on the way in which patients understand their symptoms and the manner in which these could be framed in a medical and cultural context that give them meaning. The distinction between acute pain and chronic pain, often supporting the historical explanation of the emergence of pain medication or, as called by David B. Morris, «postmodern pain», is not a prerogative of the twentieth century nor can it alone explain the development of palliative medicine (Morris, 1998). Nor does the limited use of this expression explain the systematic concealment of human groups whose living conditions would today be considered deplorable.

The emergence of a science of pain is not, therefore, due to the internal development of science. The scientific and cultural colonisation of the harmful experience –clinical concern in the field of subjectivity– is neither based on, nor can be explained by, a teleological sequence making pain medication the logical conclusion of all suffering of bygone humanity. Chronic pain has emerged as a clinical condition once the flow of life described by Elliotson’s patient could be transformed into an experience likely to last for days, weeks or years. Its appearance as an object of science is not the end of the story, but the beginning of another, which has allowed the recognition of a way of life that, until then, had been diluted and hidden, without clinical significance or cultural value.

Hence pain medication partially corresponds to the development of clinical practice linked to many long-term diseases, whose emergence in the field of biomedicine is also considered recent (Arney and Bergen, 1983). Its emergence cannot be linked to the culmination of a historical process associated with the process of civilisation, for example, but must be framed in terms of how our contemporary world has been capable of transforming continuous pain into an experience worthy of scientific inquiry, clinical treatment and, equally important, with a cultural significance.

NOTES

1. Munk mentions Ferriar’s treatise (Manchester) On the Treatment of the Dying, and the works of Paradys and Sir Henry Halford. Although, in his opinion, death was a transition that usually happened without suffering, medicine should strive to improve the adverse conditions that may arise. (Back to text)

2. Throughout the nineteenth century, improved living conditions led to increased life expectancy, resulting in more people suffering chronic diseases. Cancer, for example, known from time immemorial, only began to be perceived as a problem requiring serious scientific attention in the early twentieth century (De Moulin, 1983). On the history of breast cancer, see also Robert A. Aronowitz (2007). Equally interesting regarding the social nature of disease, Barron H. Lerner (2001). (Back to text)

3. The IASP (International Association for the Study of Pain) definition of pain is worth quoting in full:

«Unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage or described in terms of such damage. Note: the inability to communicate verbally does not prevent a person from possibly experiencing pain and from needing proper treatment to relieve it. Pain is always subjective. Each individual learns the application of the word from experiences related to injuries suffered during childhood. Biologists agree that stimuli causing pain can damage the tissue. Accordingly, pain is the experience we associate with real or potential tissue damage. It is undoubtedly a sensation localised on one or more body parts, but it is also always unpleasant and therefore an emotional experience. There are experiences that resemble pain but are not unpleasant, for instance, a prick, which should not be considered pain. In other abnormal unpleasant sensations (dysaesthesias) pain may also be present but not necessarily, because, subjectively, there may not be the usual sensory qualities of pain.

Many people complain of pain with no tissue damage or any likely pathophysiologic cause; usually this happens for psychological reasons. Generally, there is no way to distinguish this feeling from that produced by tissue damage if we consider the subjective report. If the subject believes that what he feels is pain and reports this in the same way as if it were pain caused by tissue damage, this must be accepted as pain. This definition avoids linking pain to stimuli. The activity induced in the nociceptors and nociceptive pathways by a noxious stimulus is not pain, which is always a psychological state, although we note that usually pain has a related physical cause». (Back to text)

4. Regarding neurasthenia, see Drinka (1948). On PTSD, Brewin (2003) and Gijswijt-Hofstra and Porter (2001), especially Chapter 1: Porter, «Nervousness, Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century Style: From Luxury to Labour». On chronic fatigue syndrome, which emerged in the mid-eighties, see Aronowitz (1998) Chapter 1: «From Myalgic Encephalitis to Yuppie Flu. A History of Chronic Fatigue Syndromes». (Back to text)

REFERENCES

Arney, W. R. & B. J. Bergen, 1983. «The Anomaly, the Chronic Patient and the Play of Medical Power». Sociology of Health and Illness, 5(1): 1-24.

Aronowitz, R. A., 2007. Unnatural History. Breast Cancer and American Society. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge.

Baszanger, I., 1998. Inventing Pain Medicine. From the Laboratory to the Clinic. Rutgers University Press. London.

Beinart, J., 1988. «The Snowball Effect: The Growth of the Treatment of Intractable Pain in Postwar Britain». In Mann, R. D. (ed.). The History of the Management of Pain. The Parthenon Publishing Group. New Jersey.

Bland-Sutton, J., 1903. Tumors. Innocent and Malignant. Their Clinical Characters and Appropriate Treatment. Cassell and Company. London, Paris, New York.

Bonica, J. J., 1976. Proceedings on the First World Congress of Pain. Raven Books. New York.

Clark, D., 2003. «The Rise and Demise of the Brompton Cocktail». In Meldrum, M. L. (ed.). Opioids and Pain Relief: A Historical Perspective. IASP Press. Seattle.

De Moulin, D., 1983. A Short History of Breast Cancer. The Hague, Dordrecht, Martines Nijhoff Publishers. Boston.

Drinka, G. F., 1984. The Birth of Neurosis: Myth, Malady and the Victorians. Simon and Schuster. New York.

Falret, J. P, 1822. De l’hypochondrie et du suicide. Considérations sur les causes, sur les siège et le traitement de ces maladies, sur les moyens d’en arrêter et d’en prévenir le développement. Croullebois. Paris.

Fell, W., 1857. Treatise and Cancer, and Its Treatment. John Churchill. London.

Gijswijt-Hofstra, M. & R. Porter, 2001. Cultures of Neurasthenia. From Beard to the First World War. Rodopi. Amsterdam, New York.

Jeffreys, D., 2004. Aspirin: The Remarkable Story of a Wonder Drug. Bloomsbory. London.

Jewson, N. D., 1979. «The Disappearance of the Sick Man from the Medical Cosmology, 1770-1870». Sociology, 10: 225-244.

Lériche, R., 1949. La chirurgie de douleur. [1937]. Masson & Cie. Paris.

Lerner, B. H., 2001. The Breast Cancer Wars. Hope, Fear and the Pursuit of a Cure in Twentieth-Century America. Oxford University Press. Oxford.

Meldrum, M. L., 2003. «A Capsule History of the Pain Management». Journal of the American Medical Association, 290: 2470-2475.

Merskey, H. (ed.), 1986. «Classification of Chronic Pain: Descriptions of Chronic Pain Syndrimes and Definitions of Pain Terms. Pain, 3: 1-225.

Morris, D. B., 1998. Illness and Culture in the Postmodern Age. University of California Press. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London.

Munk, W., 1887. Medical Treatment in Aid of Easy Death. Longmas, Green and Co. London.

Natas, S., 1996. The Relief of Pain: The Birth and Development of the Journal Pain from 1975 to 1985 and its Place within Changing Concepts of Pain. B. Sc. Dissertation. University College.

Ryle, J. A., 1935. The Aims and Methods of Medical Science. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge.

Ryle, J. A., 1948. The Natural History of Disease. [1928]. 2nd edition. Oxford University Press. London, New York, Toronto.

Snow, H., 1890. The Palliative Treatment of Incurable Cancer, with an Appendix of the Use of the Opium-Pipe. J & A Churchill. London.

Snow, H., 1893. Cancers and the Cancer-Process. J & A Churchill. London.

Stoddard Holmes, M., 2003. «The Grandest Badge of His Art: Three Victorian Doctors, Pain Relief, and the Art of Medicine». In Meldrum, M. L. (ed.). Opioids and Pain Relief: A Historical Perspective. IASP Press. Seattle.

Szabo, J., 2009. Incurable and Intolerable. Chronic Disease and Slow Death in Nineteenth-Century France. Rutgers University Press. New Brunkswick, New Jersey, London.

Turnbull, A., 1837. A Treatise on Painful and Nervous Diseases, and on a New Mode of Treatment for Diseases of the Eye and Ear. John Churchill. London.

Wall, P. D. & R. Melzack, 1996. The Challenge of Pain. [1982] Penguin. London.