Nature’s Image

The role of photography in environment research and reporting

The widespread notion that a picture is worth a thousand words has always been present in the relationship between man and nature. Even at the dawn of mankind, cave dwellers felt the need to graphically capture the animals they saw or hunted in order to show them to the other members of their tribe. Cave paintings and petroglyphs are an amazing phenomenon found the world over, whether in the caves of the Mediterranean lands or the confines of South America, the Sahara or in faraway Australia. Those images show scenes of wildlife in nature that are not unlike what today’s photographic essays published in magazines might show.

«Back at the beginnings of scientific discovery, naturalist illustrators were an essential component of any fieldwork or expedition that set off in the search for new lands, plants and animals»

Back at the beginnings of scientific discovery, naturalist illustrators were an essential component of any fieldwork or expedition that set off in the search of new lands, plants and animals. They accompanied the naturalists, immortalizing the new species they discovered in drawings and paintings. It was not until 1816 that the Frenchman Nicéphore Niepce succeeded in taking the first photographs. It seems the first to use this new medium to capture natural elements was the Englishman William Henry Fox Talbot, who started taking pictures of flowers, leaves and feathers in 1839. As of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, photography became popular and grew to be an indispensable tool for scientific documentation.

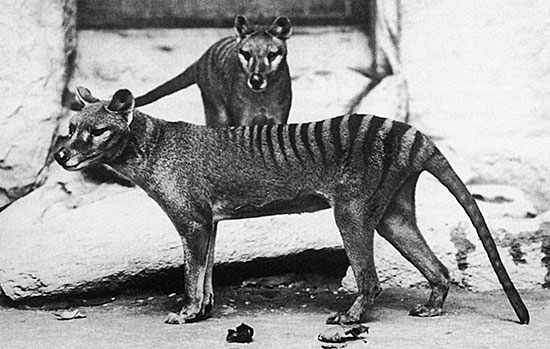

Throughout history, mankind has brought about the extinction of many animal and plant species. In many cases, all that remains of them is a skeleton or an illustration by former naturalists. But nothing is more shocking than to see actual photographs of species like the Quagga zebra or the Thylacine (Tasmanian wolf), which became extinct during the last century. This photograph, taken in 1906 at the Washington Zoo, is a valuable testimony of some of the last living specimens of this enigmatic marsupial wolf (Thylacinus cynocephalus), declared extinct in 1936. / E. J. Keller

Unfortunately, nowadays some of those animals embodied in sepia ink on the walls of caves, or depicted on the pages of natural history manuscripts, are no more. Similarly, now all that remains of certain species such as the Tasmanian wolf (Thylacinus cynocephalus) or the Quagga zebra (Equus quagga quagga), which some of the first photographers managed to capture live, are some stuffed specimens or a few photographs. A valuable legacy for future generations to realize what has been lost. Today’s nature photographers are the heirs to those pioneers in image, and currently they are also capturing landscapes and wildlife species for posterity, which the next generation might not otherwise be able to see.

PHOTOGRAPHY AND ENVIRONMENTAL RESEARCH

Throughout history, scientists have frequently used photography for the documentary record of reality it provides (or should provide). For instance, in the eighties, Catalan ornithologists used series of photographs taken of the bearded vulture and Bonelli’s eagle in flight as the basis for their work and illustrations showing the progressive stages of plumage of these birds of prey, a natural process hitherto little-known. The photographs were published in scientific papers and consulted by specialists to calculate the approximate age of birds observed in nature.

«Nature Photographers capture landscapes and animals or plant species for posterity, which subsequent generations may otherwise be unable to see»

On other occasions, photography has acted as witness, verifying the observation of unusual species or recording rarely observed behaviour, such as chimpanzees using tools. Similar works by photographers, who often spend endless hours in a hideout to photograph an animal, have led to the discovery of certain relevant facts. During expeditions to remote lands, often the plants or animals photographed would turn out to be unknown to Science, or thought to have been missing for decades. In reports published in journals, photographers often reflect the fieldwork and protection projects carried out by biologists, showing society the effort and worth of their work. On a personal note, I have spent over a decade photographing the work carried out in a project to reintroduce the falcon in the city of Barcelona, and the images obtained have proved useful, publicizing the project in a variety of places.

PHOTOGRAPHY’S ROLE IN REPORTING AND DEFENDING NATURE

In today’s society, the image wields remarkable influential power. Professional photographers raise society’s awareness of the progressive deterioration of our planet –and the beauty it still holds– through their photographic reports of natural ecosystems or endangered animal species, published in books and magazines or broadcast via other media. This affords it a central role when it comes to raising public awareness of the importance of nature.

There have been many cases, and I believe there will be even more, where images have gone beyond mere disclosure –somehow making us feel a deep admiration and respect for something by knowing it better–. Personally, I went from studying and photographing birds of prey and wildlife in the Pyrenees to participating actively in the creation of study groups and the defence of nature. Fortunately there are quite a few photographers who, in our relationship with the natural environment, have gone beyond the mere act of photographing it and have become involved in its defence and protection.

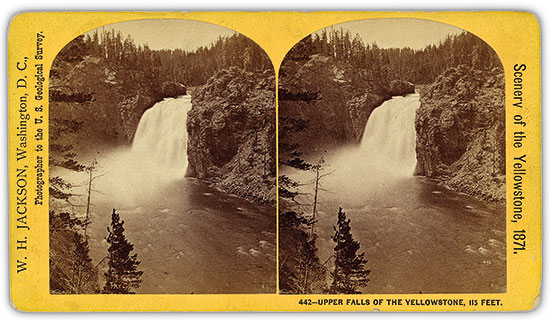

Little did William Henry Jackson, pioneer photographer, imagine that the photographs he took in 1871 as part of a scientific expedition to the American West would lead to the Yellowstone National Park becoming the world’s first National Park. His pictures were shown to members of the U.S. Congress, leading to the designation of this protected natural area in 1872. Many of his pictures, like this one of Yellowstone Falls, were stereoscopic, i.e., taken with a camera with two lenses, which could then be seen in three dimensions through a simple visor device. 3D images are not a modern invention. / W. H. Jackson/U.S. Geological Survey Photographic Library

In some cases, the photographer’s work has been crucial to the preservation of a specific nature reserve. In the 140 years of the history of photography there are many examples: the best known is the case of the photographs taken by, the American, William Henry Jackson (1843-1942) during a geological expedition to the Grand Canyon and Yellowstone. Those images were crucial for members of the United States Congress to declare the creation of the first national park in the world, in 1872. On recognizing the valuable contribution made by photographers, the National Park Service of the U.S.A. ruled that photography should be facilitated and enhanced in these protected natural areas. Somewhat contrary to what happens in countries like ours where, often, rangers and park managers see the photographer as an annoying intruder.

In the U.S.A. there is a long tradition of photographers linked to conservation. An author as well known as Ansel Adams took advantage of his fame to write to governors, and even to the country’s president, complaining about the environmental damage he discovered in the course of his work. In the nineteen-sixties, the photographer Eliot Porter published an awe-inspiring book called The Place No One Knew. He published pictures he had taken of Glen Canyon in Colorado, an exceptional place in the Utah desert, just before was totally flooded by reservoir waters in 1963. The book became the ultimate tribute to a place man had destroyed, one which later generations would never know. The impact of the book is still resounding today; in fact, a few years ago it was reissued and now the Glen Canyon Institute is requesting that the dam should be destroyed, to partially recover that magnificent landscape.

«Behind every wildlife photograph there are many hours of study and knowledge, work, effort, cold or heat, exhaustion and economic investment»

Something similar to what occurred in Yellowstone National Park happened in Doñana, in the fifties, and in Monfragüe, in the eighties, nature reserves in Spain where this task of awareness raising was decisive in making their exceptional value known abroad, thereby halting the progressive destruction of these ecosystems by National administration. Thus the scientists J. A. Valverde, in Doñana, and Jesus Garzon, in Monfragüe, understood the issue, seeking photographers as allies to help them in their work, knowing the beneficial effect it would (and did) have in protecting these areas. Today both sites are protected as registered National Parks.

Another place with a long tradition of conservationist photographers is the island of Tasmania. In the eighties and nineties, photographers Olegas Truchanas and Peter Dombovskis actively collaborated in an effort to preserve certain spots on this Australian island, which hydroelectric exploitation plans were set to destroy. Both eventually died in different accidents while engaged in photographing wild natural spaces.

Thanks to the research and observation made by some nature photographers, new animal species have been discovered, or presumably extinct species have been rediscovered, and little-known behaviours documented. Such documentary work and subsequent public dissemination helps to raise awareness of the need to protect certain valuable natural landscapes. / E. Vicens

With particular reference to animal species, a good example is the monograph published in 1933 by the Swedish photographer Bent Berg on the Indian rhino, which was partially responsible for its subsequent protection. And one cannot underestimate the impact of the striking images of bears and wolves in magazines, books, posters and calendars, helping to redeem these two species that have traditionally been abhorred by mankind.

Canon, the photography company, provides a curious example of how the world’s most endangered species appear in advertising published in the American edition of National Geographic for neigh on thirty years. Each advert shows an endangered animal species in a photograph with a caption commenting on its current situation, thus reaching the widest audience possible. This series has ended up being a classic and is still published today.

There is nothing like a picture to examine the physical features of an animal in detail, such as the young bearded vulture (Gypaetus barbatus). Photographs of this endangered species were used in the eighties to study the bird’s plumage moulting process. / O. Alamany

There are many photographers who sometimes give away their work, free of charge, to environmental NGOs to collaborate on numerous projects for conservation and nature study. Countless are the campaigns defending natural beauty spots or species that are illustrated by the altruistic work of the photographers! In 1997, Fernando Bandín and I headed a project run by SEO-BirdLife. It involved the publication of a book on the history of nature photography (Fotógrafos de la naturaleza), the proceeds of which were used to acquire land for conservation in the Delta del Ebro, an important wetland area in Catalonia. Most of the photographers participating from all around the world gave their images for free.

The International League of Conservation Photographers, set up in 2005, is the latest attempt to combine photography with conservation. iLCP was conceived from the idea that unless people have a sensory relationship with the target to be saved, it is difficult to establish an emotional bond. For many people, the only experience of wild animals is limited to one they may have had in a zoo. Some striking images of endangered species or habitats can be highly persuasive and the idea behind iLCP is to make sure conservation campaigns are illustrated with good and compelling images.

Behind every wildlife photograph there are many hours of study and knowledge, work, effort, cold or heat, exhaustion and economic investment. How can one properly assess the value of a photograph of a vulture eating a bone in a snowy winter landscape, or shots of a far-off almost inaccessible location? Its value is incalculable, like the contribution that nature photographers have made and will make to defending and studying the environment.