Educational tools for better eating

Origin and evolution of dietary guidelines in Catalonia

Dietary guidelines are educational tools based on scientific evidence and on the characteristics of the target population. They must make it easier for people to make better food choices and therefore improve their health, as well as take better care of their environment. The first guidelines used different graphic ideas, until the so-called food triangle or pyramid model, first popularised in the 1990s, became the representation of reference for decades. More recently, the «healthy plate» has come to complement or replace the pyramid in many contexts, although other organisations, such as the Public Health Agency of Catalonia, have chosen to change the approach and design different and innovative guidelines.

Keywords: dietary guidelines, food pyramid, healthy plate, community nutrition, public health.

Definition and background

Dietary guides are educational tools that adapt scientific knowledge related to nutritional requirements and food composition, as well as their effects on human health, into simple practical messages designed to help the population make better-informed decisions. This should allow individuals to choose their food intake better and can ultimately promote health and reduce the risk of food-related diseases (Manera & Cervera, 2019). Scientific publications are increasingly insisting that dietary guidelines should also consider other factors such as the impact of food models on the environment and on the social, productive, and commercial fabric of societies; however, for the moment, very few organisations have acted upon this advice (Bechthold et al., 2018; FAO, 2020a; González & Garnett, 2018; Herforth et al., 2019).

«Dietary guidelines are educational tools based on scientific evidence to help people make better food choices»

For guidelines to be useful, they must consider cultural, anthropological, educational, social, and economic factors, as well as the usual diet of the target society. Thus, every country or food culture should have its own dietary guidelines which target the general populations of specific groups such as health professionals, consumer associations, etc. (FAO/WHO, 1998; Manera & Cervera, 2019).

Although instances of dietary guidelines were already available at the end of the nineteenth century in the USA, it was between 1916 and 1930 that the North-American Department of Agriculture first disseminated guidelines based on food groups and domestic measures. The picture shows two bulletins used to improve food habits for children aged from three to six years old. / UNT Digital Library

«Dietary guidelines are not always free of conflicts of interest and also compete with many other messages from different sources»

These messages should be based on the best available evidence and must be brief, specific, and clear. Their content is often accompanied by visual aids such as icons or graphic representations (drawings, shapes, classifications, etc.) to better communicate their recommendations. The images provide more than just qualitative information because one of the goals of dietary guidelines is to convey quantitative information regarding the recommended frequency, proportion, and quantity of specific foods or food groups. In this sense, the two most common shapes used in recent decades were circles (with radii separating food groups in areas of different size according to their nutritional similarity and depending on their relative recommended proportional intake) and, from the early 1990s, the triangle (commonly known as the food pyramid). However, many European countries including Germany, the Netherlands, Portugal, and the United Kingdom, still use sectioned circles (FAO, 2020b).

«Dietary guidelines should consider aspects such as the impact of food models on the environment and the social, productive, and commercial fabric of a society»

Dietary guidelines are especially useful in the field of public health and community nutrition, so most national and local public administrations use this resource with their respective populations. These dietary education sources, which are not always free of conflicts of interest (Mozzaffarian & Forouhi, 2018), also compete with many other messages from different sources (advertising, media, social networks, etc.), making it more challenging for them to become widely spread and gain more adherence.

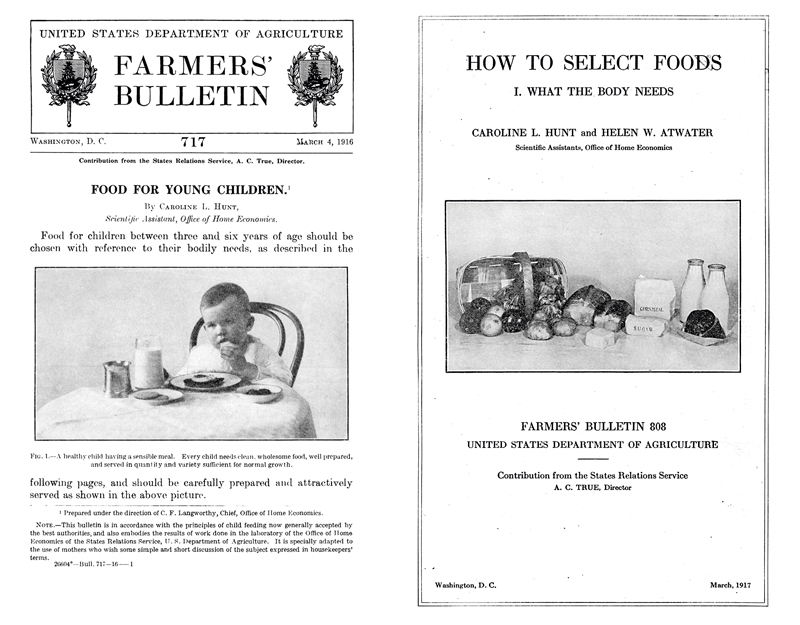

The basic seven. A guide to good eating was published in 1943. It included a wheel evenly separating seven food groups and proposed a diet based on nutritional adequacy. / U. S. National Archives and Records Administration

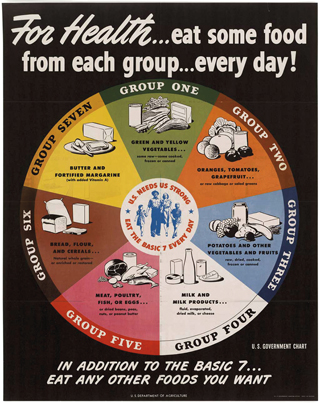

Although there are instances of guidelines being published from the end of the nineteenth century in the USA (National Agriculture Library, 2019), it was between 1916 and 1930 that the North-American Department of Agriculture disseminated guidelines based on food groups and domestic measures. The basic seven. A guide to good eating was published in 1943. It included a wheel evenly separating seven food groups and proposed a diet based on nutritional adequacy (Welsh et al., 1992). Three other proposals followed in the next few years until, in 1992, the first picture of a pyramid was used to communicate dietary guidelines in the United States. It transmitted the ideas of variety, moderation, and proportion, with daily recommended intakes, and was created considering consumer patterns. It should be noted that the triangle had already been used in other countries such as Sweden in 1975.

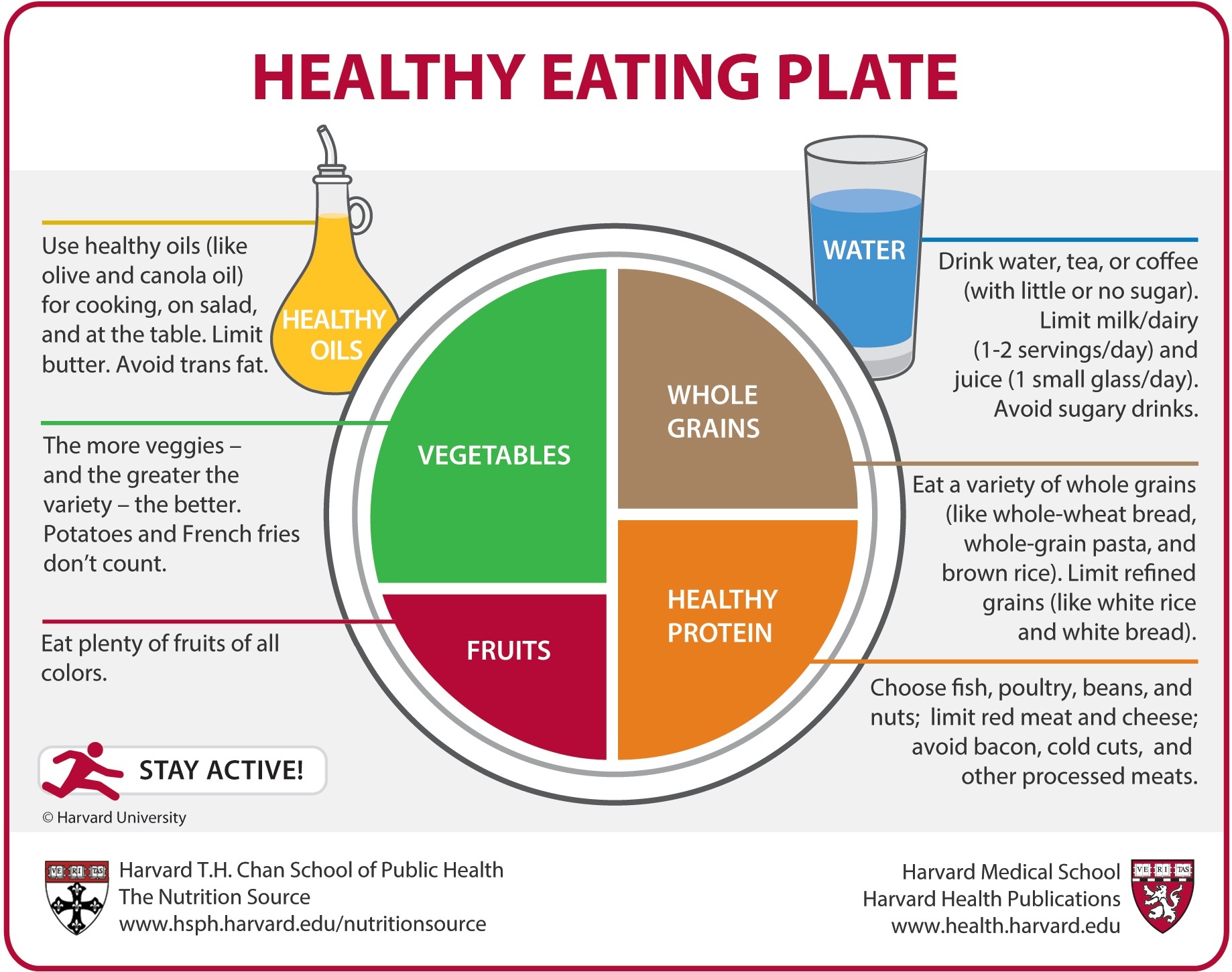

The latest US government guidelines, published in 2011, replaced the pyramid with a plate representing the proportion of the main food groups that should be included in main meals. This resource has been adapted and used by many other institutions such as the Harvard School of Public Health, Canadian Department of Health, and Basque Department of Health in Spain. In some countries like Finland and Switzerland, and in regions such as Catalonia, the plate has been used to complement the pyramid. Some advantages attributed to the plate are a better applicability of the message to the main meals and the fact that it does not include unhealthy foods. Conversely, the pyramid conveys what proportion of every food group should be included globally.

After several proposals, the food pyramid was first used in US dietary guidelines in 1992. It transmitted the ideas of variety, moderation, and proportion, with daily recommended intakes, and was created considering consumer patterns. / National Agricultural Library

In Europe, many countries (for example, Austria, Finland, Greece, Israel, Spain, etc.) still use the pyramid; however, some have found new ways to communicate the message. This is the case of Belgium’s inverted triangle or Sweden’s three key messages (FAO, 2020b). The guidelines in different countries coincide in several food recommendations (food variety, prioritisation of fruits, vegetables, legumes, etc., and limited intake of sugar and salt, etc.), but advice regarding meat, dairy products, fats, whole grains or dried fruit, for instance, was more variable (Herforth et al., 2019).

In 1995, three years after it was introduced in the United States, the Spanish Society of Community Nutrition (SENC) reached an agreement and presented the first healthy eating pyramid. After several updates over the years, this image remains the reference for most of the Spanish population, as well as for health professionals (Aranceta-Bartrina et al., 2019). In 2005, the Spanish government – within the NAOS Strategy (Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity Prevention) of the Ministry of Health, Consumer Affairs and Social Welfare – also published the NAOS pyramid, which combined healthy eating and physical activity recommendations. It distributes food items according to their recommended intake: «daily, several times» for rice, pasta, potatoes, vegetables, fruit, milk and milk-derivates, and olive oil; «several times a week» for meat, fish, eggs, vegetables, dry fruit; or «occasional» for items such as sweets, soft drinks, and ice cream (Agencia Española de Seguridad Alimentaria y Nutrición, 2005).

First food guidelines in Catalonia

The healthy plate, also known as the Harvard plate, represents the proportion of each food group each of our main meals should contain. / Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health

The precedents in the design of food education tools date back to the first nutritional survey in Catalonia, carried out in 1988–1989 by the Department of Health. At the time, and based on the data obtained in the study, a poster and leaflet of recommendations were published and distributed, mainly in primary health care centres. They showed what they called the Food table, which presented six basic food groups, as well as some recommendations regarding their consumption. It is worth noting that the guide did not include unnecessary or unhealthy foods (sweets, candy, pastries, salted snacks, etc.), which at the time were already separated from the basic food groups. It should also be noted that the consumption of wine or other alcoholic beverages was not contemplated in these recommendations.

Healthy eating Pyramid (2005 and 2012)

In 2005, the Catalonian Department of Health led the PAAS strategy (integral plan for health promotion through physical activity and healthy eating) to promote health and prevent obesity. The initiative was born in accordance with the NAOS strategy (2006) and the world strategy on diet, physical activity, and health from the World Health Organization (WHO, 2004), which urged member countries to start strategies to promote lifestyle changes that would contribute to preventing obesity and chronic diseases.

«Dietary guidelines must change because the science keeps evolving and its socio-economic, demographic, and cultural characteristics also change over time»

As recommended at the international and national level, the PAAS incorporated actions on two of the main determinants of obesity: food and physical activity. The actions were mainly circumscribed to the educational, community, health care, and labour fields, and transversally incorporated a great range of institutions, departments, universities, foundations, and community resources. The underlying base for the PAAS was the evidence that multidisciplinary, multifactorial, and comprehensive approaches were more effective in promoting habits and lifestyle changes. The PAAS based its actions on proposals aiming to improve environments (making them healthier) and informing, training, and empowering professionals and citizens (empowerment strategy).

In this environment, the first steps were taken to develop a new tool to promote healthy eating for the Catalonian population based on the 2004 SENC pyramid. To start the process of adaptation and consensus, a working group was formed with professionals from the fields of nutrition, education, food safety, and physical activity. In this way, the Department of Health reached an agreement regarding the first healthy eating pyramid and published the guidelines in 2015.

In Spain, in 1995, the Spanish Society of Community Nutrition (SENC) reached an agreement and presented the first healthy eating pyramid. After several updates over the years, this image remains the reference for most of the Spanish population, as well as for health professionals. / SENC

The main difference with the SENC pyramid was that this one focused on not recommending alcoholic beverages (wine and beer). At the time, and despite the association between a healthy Mediterranean diet and moderate consumption of wine, there was enough evidence regarding the risks of alcoholic beverages to justify the removal of recommendations about wine and beer (Corrao et al., 2004; Galán et al., 2017). Furthermore, the pyramid was considered a tool aimed at the entire population, including children and pregnant women, for whom avoiding alcohol is an especially important message.

Around 2011, a new proposal emerged in the United States, which broke away from the previous graphical representations used in most countries: the healthy plate. As mentioned above, it represents the proportion of each food group we should have in our main meals. Authorities in Catalonia also started doubting the usefulness of the pyramid and considered the possibility of adapting the healthy plate for use in their context. In addition, evidence had been accumulating since 2005 about the benefits of increasing the intake of fibre and whole foods to improve health and prevent diseases, as well as evidence for the positive effects of eating fruit, vegetables, and legumes. At the same time, publications on the harmful effects of abusing sugar and sugar-sweetened beverages, as well as of salt and salty foods, started gaining traction. These facts, together with new data about the prevalence of obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and other chronic illnesses included in the Catalan health survey, ESCA (Generalitat de Catalunya, 2010–2014), reinforced the need to update the messages transmitted by the pyramid.

Therefore, in 2011, an update was proposed for the 2005 healthy food pyramid within the PAAS strategy framework. This rework was based on the review and consensus work carried out by a panel of experts in nutrition, food, food safety, communication, and education.

In 2005, the Catalan Department of Health reached an agreement regarding the first healthy eating pyramid. The picture shows the latest update to this tool (2012). / Generalitat de Catalunya

The main contributions of the updated 2012 version were a) grouping grains and tubers foods (bread, pasta, rice, potato) and legumes and vegetables, fruits, olive oil, and dried fruit together, to encompass all plant-based foods represented in a healthy Mediterranean diet; b) an increased presence of legumes (due to their nutritional value, adaptability into many different types of dishes, and low price) both with grains and tubers and with protein-rich foods (lean meat, fish, and eggs); c) the promotion of fibre-rich foods (legumes, dried fruit, fruit, and vegetables, etc.), especially whole cereals (bread, pasta, and rice, etc.) due to their proven health benefits; d) a preference for low-fat dairy products (skimmed milk) that have lower cholesterol and saturated fat content; e) more detail about foods for occasional or moderate intake, including juice and sugar-sweetened beverages, fried and salty snacks, and fatty and processed meats; f) a recommendation to lead an active lifestyle both in terms of everyday life and in outdoor leisure activities; g) a preference for fresh, local, and seasonal foods, and a recommendation to eat at a table and to be careful to eat in moderation and in company; and h) a recommendation to reduce the amount of sugar and sugar-sweetened foods, as well as salt and salty foods consumed.

Together with this update, a consensus leaflet was published, based on the new pyramid, and including a list of recommendations, and the new healthy plate tool to structure main meals.

Small changes for better eating

In 2017, five years after the publication of the previous healthy eating pyramid in 2012, its content had to be updated again. A review was carried out following the steps indicated by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA, 2010) to consider all the scientific evidence relating specific foods and eating patterns with a higher or lower risk of suffering particular diseases. They also assessed the environmental impacts and social and economic structures associated with the food model promoted in these dietary guidelines, following recommendations from the latest scientific publications (Bechthold et al., 2018; FAO, 2020a; González & Garnett, 2018; Herforth et al., 2019). Finally, when it came to choosing which foods and behaviours to promote or discourage, and bearing in mind that these recommendations would be based on the foods actually consumed by the population the guide was directed towards, information from the Spanish (ENALIA and ENALIA 2) and Catalan (ESCA) food, nutrition, and health surveys were considered.

After a bibliographic search for publications related to these three fields (health and food patterns, food and diet surveys of relevant contexts, and the environmental impact of the food model), a record was created with the latest food guidelines from other countries such as France and Sweden, in order to analyse their acceptance by the population and aspects arising from their implementation. With all this documentation, a conference was organised under the banner «Rethinking the pyramid», in which professionals from the fields of nutrition, medicine, nursing, public health, NGOs and the third sector, communication and dissemination, and research all participated. Key questions were considered on how to improve the healthy-eating pyramid, and whether the format should be replaced with another option such as the healthy eating plate.

Once these contributions had been examined, and considering the aforementioned technical work, the team of dietitians and nutritionists at the Public Health Agency of Catalonia, ASPCAT, proposed a change in the scope of the pyramid update and presented a new educational tool based on a Swedish campaign called Find your way (launched in 2015), with adaptations to Catalonia’s social context, priorities, production, and food availability.

In 2018, the Public Health Agency of Catalonia presented the educational tool Petits canvis per menjar millor (“Small changes to eat better”), based on the Swedish campaign Find your way (2015), but adapted it to Catalonia’s social context, priorities, production, and food availability. / Generalitat de Catalunya

The final result was structured into three groups of recommendations: which foods and behaviours should be promoted, ones that should be reduced, and those which should be changed for better quality or healthier and more environmentally friendly alternative behaviours. Thus, the «More» group included foods with a healthier nutritional profile (fruits and vegetables, legumes, and dried fruit) and a lifestyle associated with improvements in health indicators, i.e., an active and social lifestyle. The «Switch to» group aimed to improve our eating by substituting regular bread, pasta, and rice with wholegrain alternatives, a preference for virgin olive oil over other vegetable oils or fats, water as the main drink, and seasonal and local produce. Finally, the «Less» group included foods and products whose intake should be reduced (salt and salty foods, sugar and sugar-sweetened beverages, red and processed meat, and ultraprocessed foods) because studies and surveys have related the abuse of these items with a higher prevalence and risk of suffering chronic diseases.

The main image of the Petits canvis per menjar millor (“small changes for better eating”) guide was accompanied by an 82-page document explaining each food item and why it was or was not recommended, providing quantitative and qualitative advice, practical tips for following this advice, trivia, data, interesting definitions that should be remembered, cooking resources such as recipes, a section with advice on how to better protect our environment, dissemination links and resources, and more than 80 references to the information used to develop the guide. All the materials derived from these guidelines were revised and improved upon by 52 professionals from the fields of nutrition, education, community health, and communication, among others. The project also collaborated with seven universities, six scientific societies and professional associations, and ten organisations, foundations, patient associations, and NGOs.

«Multidisciplinary, multifactorial, and comprehensive approaches are more effective in promoting habits and lifestyle changes»

A final reflection

Dietary guidelines should help the population make better food choices; therefore, they should be based on the latest scientific evidence and be adapted to their target population. Furthermore, they must change with the times, because science keeps evolving and the population and its socio-economic, demographic, and cultural characteristics also change over time. Apart from regular updates, guidelines must be developed using adequate, systematic, and transparent methodological strategies (Rabassa, 2019) and must include their own verification process in order for their messages to be rigorous and efficient. In this sense, there is still a long way to go (Rabassa et al., 2018; Zeraatkar et al., 2019). However, even though informative, educational, and empowering strategies – such as dietary guidelines – are important and necessary, they must be accompanied by contextual interventions. In other words, by strategies that make it easier for the population to make healthier choices.

References

Agencia Española de Seguridad Alimentaria y Nutrición. (2005). Pirámide NAOS. Retrieved November 19, 2019, from https://www.aecosan.msssi.gob.es/AECOSAN/web/nutricion/subseccion/piramide_NAOS.htm

Aranceta-Bartrina, J., Partearroyo, T., López-Sobaler, A. M., Ortega, R. M., Varela-Moreiras, G., Serra-Majem, L., Pérez-Rodrigo, C., & The collaborative group for the dietary guidelines for the Spanish population (SENC). (2019). Updating the food-based dietary guidelines for the Spanish population: The Spanish Society of Community Nutrition (SENC) Proposal. Nutrients, 11(11), 2675. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11112675

Bechthold, A., Boeing, H., Tetens, I., Schwingshackl, L., & Nöthlings, U. (2018). Perspective: Food-based dietary guidelines in Europe-scientific concepts, current status, and perspectives. Advances in Nutrition, 9(5), 544–560. http://doi.org/10.1093/advances/nmy033

Corrao, G., Bagnardi, V., Zambon, A., & La Vecchia, C. (2004). A meta-analysis of alcohol consumption and the risk of 15 diseases. Preventive Medicine, 38(5), 613–639. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.11.027

EFSA. (2010). EFSA panel on dietetic products, nutrition, and allergies scientific opinion on establishing food-Based dietary guidelines. EFSA Journal, 8(3), 1460. https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/efsajournal/pub/1460

FAO. (2020a). Guías alimentarias y sostenibilidad. Retrieved February 12, 2020, from http://www.fao.org/nutrition/educacion-nutricional/food-dietary-guidelines/background/sustainable-dietary-guidelines/es/

FAO. (2020b). Guías alimentarias basadas en alimentos. Retrieved February 12, 2020, from http://www.fao.org/nutrition/educacion-nutricional/food-dietary-guidelines/home/es/

FAO / WHO. (1998). Preparation and use of food-based dietary guidelines: report of a joint FAO/WHO consultation. https://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/nutrientrequirements/WHO_TRS_880/en/

Galán, I., Aragonés, N., & Villalbí, J. R. (2017). La recomendación del consumo de alcohol en las «Guías alimentarias para la población española». Un mensaje demasiado ambiguo. Nutrición Hospitalaria, 34(4), 1004–1005.

Generalitat de Catalunya. (2010–2014). Results of the Catalan health survey (ESCA). 2010, 2011, and 2012. Retrieved November 22, 2019, from https://salutweb.gencat.cat/ca/el_departament/estadistiques_sanitaries/enquestes/esca/resultats_enquesta_salut_catalunya/index.html#googtrans(ca|en)

González, C., & Garnett, T. (2018). Platos, pirámides y planeta. Novedades en el desarrollo de guías alimentarias nacionales para una alimentación saludable y sostenible: evaluación del estado de la situación. FAO. http://www.fao.org/3/i5640es/I5640ES.pdf

Herforth, A., Arimond, M., Álvarez-Sánchez, C., Coates, J., Christianson, K., & Muehlhoff, E. (2019). A global review of food-based dietary guidelines. Advances in Nutrition, 10(4), 590–605. https://doi.org/10.1093/advances/nmy130

Manera, M., & Cervera, P. (2019). Alimentación saludable. In J. Salas, A. Bonada, R. Trallero, M. E. Saló, & R. Burgos (Eds.). Nutrición y dietética clínica (pp. 23–32). Barcelona: Elsevier.

Mozzaffarian, D., & Forouhi, N. (2018). Dietary guidelines and health —is nutrition science up to the task? British Medical Journal, 360, k822. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k822

Rabassa, M. (2019). Guías de alimentación y nutrición: ¿qué sabemos sobre su calidad? Revista Española de Nutrición Humana y Dietética, 23(1), 5–7.

Rabassa, M., Garcia-Ribera Ruiz, S., Solà, I., Pardo-Hernandez, H., Alonso-Coello, P., & Martínez García, L. (2018). Nutrition guidelines vary widely in methodological quality: an overview of reviews. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 104, 62–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.08.018

National Agricultural Library. (2019). Wilbur Olin Atwater Papers. Retrieved November 20, 2019, from https://specialcollections.nal.usda.gov/guide-collections/wilbur-olin-atwater-papers

Welsh, S., Davis, C., & Shaw, A. (1992). A brief history of food guides in the United States. Nutrition Today, 6, 6–11.

WHO. (2004). Estrategia mundial sobre régimen alimentario, actividad física y salud. Retrieved November 20, 2019, from https://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/strategy/eb11344/strategy_spanish_web.pdf

Zeraatkar, D., Johnston, B. C., & Guyatt, G. (2019). Evidence collection and evaluation for the development of dietary guidelines and public policy on nutrition. Annual Review of Nutrition, 39, 227–247. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-nutr-082018-124610