The fact that I spent most of my teenage years surrounded by books —my father owned a bookshop— made it possible for me to access some books that were normally out of reach for people my age. Among so many books, some of them had to leave their imprint on me. There are three books, being specific, that seem to be the ones that taught me how to think.

The first one— and also the one I remember most vividly— is Darwin’s The Voyage of the Beagle, which I read with fascination. Of only a few I have so vivid memories— not only the parts regarding travels and adventures, but also other parts, like the explanation of atoll formation. The second one— read by parts and not so thoroughly— was Claude Bernard’s An Introduction to the Study of Experimental Medicine in a 1930’s Catalan translation. The third one was Fanz Boas’ The Mind of Primitive Man, an edition published around 1945 by a leftist Argentinean publishing house. Boas’ book must have been the last step in this unorganised ascent to rationality, prior acquiring a more proper education for a historian.

«There was a widespread understanding of Darwin’s theories that tried to justify a linear view of history whose climax was “Western civilisation”»

Needless to say that in the time I was reading these books, in the mid 1950’s, all of them were banned, and I could not have accessed them had it not been for my father’s bookshop. This ban should not be shocking, since, fifty years later, we can see Mrs Sarah Palin equally keen on preventing schools from teaching these things in her country.

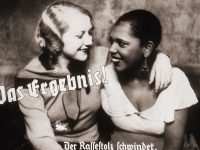

Curiosity on the one hand, and the easy access to popular science books on the other, made possible that my contact with Darwinism would not end with my teenage readings. This fact prevented me from falling into the widespread mechanicist understanding of Darwin’s theories which, in the 19th and 20th centuries, tried to justify a linear view of history whose climax was «Western civilisation», an argument used to defend colonialism— the «white man’s burden».

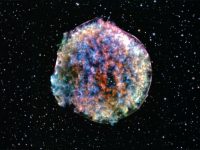

This set of ideas was based on a deterministic view of cosmos, which was linked to the study of society through a mechanistic understanding of Darwin’s ideas. This view was so widespread that, in 1872, a German scientist suggested that when knowing the exact position, direction and speed of every atom in the universe was possible, we would be able to predict all future events in human history. And also thought that science’s aim was precisely to achieve a perfect knowledge of the social world as well as the natural world. The French anarchist Charles Malato, shared this aspiration, and at the onset of the 20th century wrote: «historical science does not exist at the present moment, it is yet to be created. No writer has ever been able to do for science what Kepler, Copernicus and Newton did for astronomy; […] Laplace, Marx and Darwin for the other exact sciences: […] deducing with mathematical accuracy what causes the agitation of human molecules».

Reading books like Stephen Jay Gould’s taught me that Darwin was perfectly compatible with other views of history that fight linear views and determinisms and that seek to understand diversity and contingency. I am sure that adopting a contingent view of history can help us, just like Roger Marks claimed, to make decisions and act so as to guarantee a sustainable future for the whole humankind.