Interview with Charles Forceville

«Metaphors are probably something universal»

Expert on visuals and multimodal discourse

Language, in a strict sense, is something consubstantial to the human species. The possibility of a type communication that enhanced non-verbal communication must have been very efficient in evolutionary terms: some specialists on the origin of language, such as Tecumseh Fitch, have called this phenomenon glossogeny. In this sense, the introduction of visual representations, such as symbols or comparisons (A is similar to B), probably also helped us to develop metaphorical thinking. The use of metaphors must have been highly adaptive as well: as Charles Forceville says, the human ability to create metaphors must have meant an important evolutionary advantage for the first humans who used them. Metaphorical thinking allows us to pack a lot of information quickly and originally, as well as to establish connections with other ideas, and even to deal with hard or difficult issues in a synthetic and clear way. In their seminal book, Metaphors We Live By (1980) Lakoff and Johnson showed the fundamental role played by metaphors in human cognitive processes. Somehow, metaphorical thinking has been crucial for the understanding of reality.

Charles Forceville (Heemstede, Netherlands, 1959) is an associate professor in the Department of Media Studies of the University of Amsterdam, and one of the scholars who, following in the footsteps of Lakoff and Johnson, has best captured this biologist view of language. He has published many articles and chapters, and some books, on visual metaphors and multimodal discourse and he is a member of the advisory board in journals such as Metaphor and Symbol and Journal of Pragmatics. On the occasion of his visit to Valencia, we had the opportunity to talk to him about these matters, as well as to try to establish new links between biology and language.

«All difficult enterprises can be understood as journeys, because journeys are physical experiences»

From you point of view, what is the origin of metaphorical language? When did we start to use it?

In this respect, I follow Lakoff and Johnson. They say that we need metaphors because they are the only way in which we can conceptualize abstract and complex things. They also say that we live by a kind of «super» metaphor, which is why the theory is called «the theory of the embodied metaphor». Everything that pertains to sensory perception comes naturally to us, and we use this sensory information to conceptualize more complex and abstract things, such as time, ideas, and emotions. That is why we have metaphors such as LIFE IS A JOURNEY and TIME IS SPACE… All difficult enterprises can be understood as journeys, because journeys are physical experiences. We draw on this rich, embodied source domain to import meaning and thereby structure to more abstract concepts.

According to your view, what is the biological importance of language for the evolution of man?

I like [Michael] Tomasello’s ideas. He has speculated that the first ways of communication were embodied. He considers all this research with apes in the 1960s and 1970s trying to get them to talk was on the wrong track, because it is much more probable that gestures and facial expressions were the start of communication and that, somehow, from there our species managed to create language. Instead of pointing, we were able to say «at three days walking from here there is well» or «at the other side of the forest we will find the animals that we want to hunt». That sounds very plausible to me. This enormously helped us as a species, and that is why we are sitting here, and not a bunch of chimpanzees.

Photo: Paula Navarro

Do you think chimpanzees produce metaphors?

No, I do not think so.

Several researchers have said that perhaps, in the same situations, they are able to produce this kind of thinking.

Metaphorical thinking? Wow, I would like to read that research! I mean, Tomasello says that chimpanzees lack the notion of joint attention. That is the respect in which we, as humans, are ahead of them. I point at something and we both focus our attention on what I point to. Like Tomasello, and Herbert Clark, I think joint attention is crucial for communication, and I would say that metaphorical thinking is more complicated.

Right now, there is an exhibition about the origin of language in the science Museum of Barcelona. The exhibition’s commissary, an Austrian researcher called Wolfram Hinzen, says that without symbols there is no language. Do you agree with this idea?

I do. Language needs to be learned. It remains the subtlest and most sophisticated way to communicate, and I say that as somebody who is focusing on visuals all the time. I often say «try and make a visual syllogism», which would be a nice challenge, but it is not going to happen. Language is coded, so we need to learn the code. Without the codes of grammar and vocabulary there is no notion of symbols and of correctly stringing them together, and thus no language. Interestingly, some visuals or parts of visuals are also coded: for instance, logos, pictograms, and traffic signs. Like language, we have to learn their meaning. Sometimes we can guess it, but I think the coded aspect is crucial for sophisticated communication, and language is by far the best system for it.

«To think of a communicatively effective novel metaphor is something that requires creativity»

Following this idea… What came earlier, symbols or metaphors?

It depends on how you understand symbols. Art historians use the word symbol in a very different way than the semiotician Charles Sanders Peirce. Using symbol in the Peircean sense entails that we have to agree on what we mean by a sign: the relation between the real-world object «microphone» and the word microphone is an arbitrary one, which must be learned. This is obviously a late evolutionary development. But symbols in the art-historian sense specify a more direct, non-arbitrary link between sign and meaning. I would say metaphors are much more sophisticated, a later adaptation than symbols in this latter sense. Incidentally, the best-known journal in the field is called Metaphor and Symbol, and it almost entirely ignores symbolism. In the first twenty-five years of its existence, the word metaphor appeared 275 times in paper titles, and the word symbol only 8 times. Scholars contributing to that journal should become more interested in symbolism as well.

Yes, especially because of the role played by symbols in the evolutionary history of human species. What do you think was there first, the monomodal symbol or the multimodal symbol?

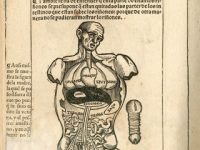

If we go to the Lascaux caves we see pictures of deer, hunters, arrows… For sure, the visual mode was there before the verbal mode. Interestingly, we seem to have forgotten about that.

Is a multimodal message more effective than a monomodal message or does it depend?

We rarely come across monomodal communication in the visual mode, because almost always the visual mode is accompanied by at least one other mode. Often by language, but in films also by music, by sound… Even silent films usually have title cards. I like working on animation films because I am intrigued by how complicated stories can be told without language; but they are still supported by sound and music. I am also very interested in wordless comics, because I think that comics artists need to think much more creatively to convey a story or to mount an argument without the use of language than with it. But in daily life, language is incredibly useful. So, to convey ideas is much more difficult for monomodal visual communication, or any other type of monomodal communication apart from language, than for multimodal communicationl.

This happens also in cartoons.

Yes. When I look for suitable examples for my papers, I really have to search through a lot just to find any without language. I think a good cartoonist sees it as a challenge to dispense with language as much as possible.

As you know, Mètode is a journal for science dissemination. From your point of view, can images help us to understand scientific communication in a better way?

That is an interesting question. In principle, I would answer affirmatively. That being said, my colleague Assimakis Tseronis analyses scientific images. I guess lay people would say: «But these are images in a scientific journal, so they must be objectively correct or true images, right?». But even for scientific images choices have been made: in what colour to print them, in what resolution, in what size… Scientific images highlight some things and hide other things, and that can be used for informative but also for manipulative purposes.

«Any model needs to adapt, it needs to evolve, otherwise it will die»

Why can metaphorical content be more effective in terms of communication?

Aristotle said that using metaphors well is a sign of genius and he was obviously talking about creative metaphors. Structural metaphors (such as life is a journey) reveal a lot about how we think, and we cannot help but use them all the time. By contrast, to think of a communicatively effective novel metaphor is something that requires creativity. If we want to explain a difficult and complex concept to non-experts, we have to systematically compare it with something with which the audience is familiar. And that is why in education and in popular science a metaphor can be a very good tool. The one thing that is not already given in the theory, however, is a good candidate to compare a complex concept metaphorically with that will do the job of clearly explaining that concept. In 1980, Mary Gick and Keith Holyoak discussed the problem of how radiologists treating cancer could avoid destroying healthy tissue by metaphorically comparing this process to soldiers who need to conquer a terrain without hitting the mines hidden there. A brilliantly insightful metaphor that helps find solutions to a complex problem.

We are continuously exposed to visual stimuli that we are constantly interpreting. How do images, in particular metaphorical images, contribute to better communication? To what extent does our evolutionary history participate in the decoding of current visual stimuli? For example, the association between the colour red and danger?

But that is a very cultural and contextual thing, isn’t it? I just returned from China, and there red is a good colour and dragons are good creatures, so red dragons are very good. By contrast, here in the West, the hero is the slayer of the evil dragon! We have to be very careful about colour symbolism. Connotations are much more cultural than we may think.

But anyway, if we talk about dark and light…

Yes, a student and I wrote a paper on «good is light, bad is dark» and of course that comes from our embodied experience. If we are lost in the dark, we panic: many bad things can happen to us. To come back to your question about visual metaphors, again we have to distinguish between creative and structural metaphors. The creative ones are often used by cartoonists and advertisers. Both want to persuade their audience of something: this is a good product, you should buy it; or this is a bad politician and you should not vote for him or her… This is persuasive communication and it helps to support a certain point of view that in itself is full of judgements and ideologies. The journey metaphor, which is not creative but structural, can be used to explain things because all difficult activities can easily be metaphorised in terms of a journey. It is very powerful. And its structural part can be enriched by creative aspects in each unique situation, so that it remains fresh and productive.

Photo: Paula Navarro

Do all cultures have their own metaphors? Do you think metaphors are something in human nature? Or do we have to learn the way to use them?

I think that some metaphors are probably universal. After Metaphors We Live By, many scholars started to investigate whether the metaphors discussed also occurred in their own language and culture, and if so, how. For instance, Ning Yu was the first scholar to take Lakoff and Johnson’s model and examine how it works in Chinese. By and large his conclusions were that we find the same metaphors, but with strong cultural components in them. To give an example, when I was in China somebody said to me: «You have a belly full of ink» and he meant something like «You are a learned guy». So in Chinese it is the belly rather than the head where thought is located. There is a basic, embodied component that probably people in the entire world will use in metaphorizing simply because we all have the same body and engage in the same bodily behaviour: we walk forwards not backwards, we do not fly, etcetera. That is the «nature» we share and it is the foundation upon which the «nurture» component is built. But what I see is that many of my colleagues in humanities departments immediately jump to the nurture part and ignore the nature part. When I mention this, they say: «Of course! But nature is not interesting! We want to see where ideologies creep in» and I respond «Well, but isn’t it fascinating that, actually, nurture is only the top of the iceberg, and that we share so much because we have the same bodies and basic needs? And that, to that extent, we naturally draw on the same metaphors?».

There is still a great gap between biology and linguistics.

Well, linguistics is a relatively scientific discipline within the humanities. Nowadays, linguists often work with corpora, they have clear research questions, their whole methodology is transparent… But in disciplines that focus on cultural objects, scholars often work with one individual datum, and they show how wonderful their analysis of that one piece is. Cultural Studies scholars have a different idea about what is considered an interesting research question than cognitivist-oriented humanities scholars.

And when you have a very scientific, materialistic point of view, you can be accused of being deterministic.

Exactly! And that is then the end of the discussion. I realise that for Cultural Studies scholars this is a difficult issue. I was educated in an English literature department and we were taught to look for whatever is unique in a literary text or in a writer. We read Shakespeare because he is better than all the rest. And the moment you do science the way you define science –namely, as pattern-finding– you need to do exactly the opposite: you have to forget about uniqueness when you want to detect patterns. I think that is something that many, many humanities scholars have a deep, emotional resistance to. Of course, I truly believe we also need to cherish and practise good humanities work that analyses art and finds the unique important! But we should do both: we should be critics, in the sense what we need to go to exhibitions, evaluate art, write reviews, etcetera. But we should also want to use our expertise in interpretation to try and help answer research questions that are central in social science and science departments –which means searching for patterns. And in order to do that, you have to do a very different kind of research. So, I am a bit worried for my colleagues, because if they do no start to think of trying also to help answer, on whatever modest level, the big questions that are facing humanity from all sides, by collaborating with scientists, I fear that they will become increasingly marginalized.

We can see very clearly what you are saying in the French school. If you see Metaphor and Symbol, it is quite difficult to find French researchers working on metaphors. Why is that? We could guess most of them are under the influence of postmodern ideas…

I think so, too! I rarely come across French scholars at metaphor conferences, either.

«I like working on animation films because I am intrigued by how complicated stories can be told without language»

Could you tell us about your current research topic?

A colleague and I are researching metaphors of depression in wordless animation films. With another colleague, I am working on metaphors in cartoons depicting the right-wing Dutch politician Geert Wilders, for a book about populist discourse edited here in Spain. With two Serbian comics scholars, I work on an experiment testing viewers’ recognition of emotions in drawn faces. But my big project now is about Sperber and Wilson’s excellent relevance theory; I think secretly that it is potentially the very best communication theory ever developed.

And what is your contribution in this area?

Relevance theory is based on spoken communication between two people. In a dialogue, I only need to be relevant to you, and you only have to be relevant to me, which already is complex enough. The relevance principle is rooted in evolution: Sperber and Wilson begin by saying that any species survives by paying close attention to what is relevant in the environment. Do I hear something there in the trees? Is it a tiger that might attack me? That is what they call the First, Cognitive Principle of Relevance. Nature, however, is indifferent to us, unlike conspecifics. The Second, Communicative Principle of Relevance presupposes that, in principle, people want to help each other. So you know that I aim to be optimally relevant to you. I may not succeed, but I try. The search for relevance is hardwired, I think evolutionarily, in our brains. In this new book I am trying to extend the theory by showing it can also work for visuals and multimodal discourse. Since it is rare for somebody to make a picture just for one other person, I have to discuss mass-communication as well. In this ambitious project I attempt to be as fair, honest, and truthful to the theory as I can. But then there comes a moment where I have to say to Sperber and Wilson: «Sorry, Dan, sorry Deirdre, but I’m talking about a different medium and I really have to take some liberties or tweak the theory to make it work for visuals».

Do you fear you might get a negative reaction?

Any model needs to adapt, it needs to evolve, otherwise it will die! In that sense, models are just like people. Unfortunately there is a tendency that once you have invested a lot of time and energy in your favourite theory, you are not likely to accept that it may have to be adapted. If you believe in the theory, though, and not only in your reputation as its father or mother, you have to accept that others will enter the debate and say «well, this works, but that does not». Dealing graciously with criticism is one of the most difficult things in life. But Sperber and Wilson are wise scholars, and I trust they see I am basically a fan trying to spread the good word.