| In the novel Around the Moon, Jules Verne describes the space voyage of three intrepid explorers, Barbicane, Nicholl, and Ardan, to which he gives this full meal after their landing:

They commenced with three plates of excellent soup, extracted from Liebig’s precious tablets, prepared from the best beef that ever roamed over the Pampas. To this succeeded several tenderloin beefsteaks, which, though reduced to a small bulk by the hydraulic engines of the American Dessicating Company, were pronounced to be fully as tender, juicy and savory as if they had just left the gridiron of a London Club House. Ardan even swore that they were «bleeding,» and the others were too busy to contradict him. Preserved vegetables of various kinds, «fresher than nature,» according to Ardan, gave an agreeable variety to the entertainment, and these were followed by several cups of magnificent tea, unanimously allowed to be the best they had ever tasted. It was an odoriferous young hyson gathered that very year, and presented to the Emperor of Russia by the famous rebel chief Yakub Kushbegi, and of which Alexander had expressed himself as very happy in being able to send a few boxes to his friend, the distinguished President of the Baltimore Gun Club. To crown the meal, Ardan unearthed an exquisite bottle of Chambertin, and, in glasses sparkling with the richest juice of the Cote d’or, the travellers drank to the speedy union of the Earth and her satellite. As evidenced by Verne’s novels, the world of the time was immensely different from ours. Geographical atlases still contained large undetailed areas, space travel was just a dream, and the conservation of food, a precariously solved issue. That is why the Liebig tablets, a technological innovation of the time, stand out in the feast. They were obtained through an arduous process that reduced beef to a water soluble extract that could be stored easily. They were sold as a tonic in pharmacies, with the promise of maintaining all the nutritional value of its expensive raw material. It is no wonder, therefore, that the product quickly became famous and entered the rations of armies and adventurers, as we can seen in the Franco-Prussian War of Henry Morton Stanley’s expedition in search of David Livingstone. It was a true revolution for the food industry, enough to launch its inventor to fame, if he needed to. When he developed the Extractum carnis Liebig, in 1847, Justus von Liebig was already the most important chemist of the time. His laboratories, first in the University of Giessen and later in the University of Munich, bustled with the activity of dozens of students from around the world. They were understandably drawn by a new teaching system that focused on experimentation and would end up being the model for the rest of university laboratories. Furthermore, they worked in a booming research field. Up to the mid-nineteenth century, the chemistry of living beings had been slowed down by the problems of analysing organic compounds. Liebig, who had fought against the limitation since he was a young pupil working under Gay-Lussac, had developed a device, the kaliapparat, which allowed to quickly and accurately measure the elemental composition of any sample. With this powerful weapon on his side, he faced problems that had hardly been addressed from a scientific point of view. Always with an eye on the practical possibilities that derived from his research, the German chemist had focused his efforts on the study of soils and on plant and animal physiology, contributing greatly to fields that were practically unknown at the time. He pioneered the use of mineral fertilisers and was the first to state that plants take carbon from the air and that nutrients oxidised within every cell in our bodies. He also dealt with human nutrition, and developed a new food classification regarding their nutritional value. The extract of meat stemmed from that research, but took its time to find a suitable application. In a Europe that suffered from shortages, as evidenced by the Irish Great Famine, any invention that needed cattle as raw material was a luxury within reach of very few people. So the extract was confined to a detailed description in specialised literature until Liebig received an unexpected visit in 1862. Georg Christian Giebert was a young German engineer based in Uruguay, who had witnessed an incredible event. In Villa Independencia, he had seen a tanning factory discard the meat of the cattle they sacrificed. Only the skin was used, the rest rot in the sun. Without a huge population to sustain and no effective way to preserve food, meat was practically worthless. One century later, the neighbouring Argentina was still proud that a hungry traveller across the Pampa could kill a cow and eat as much as they wanted provided they left the skin for the owners. The fact is that, until the appearance of refrigerated chambers, this meat was not used for much other than to prepare «charqui», an unpalatable jerky considered as sustenance for slaves. |

«When he developed the Extractum carnis Liebig, in 1847, Justus von Liebig was already the most important chemist of the time»

|

|

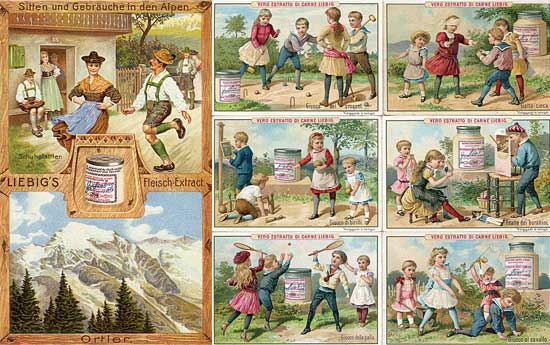

LEMCO Collectible cards edited by LEMCO. They show containers of the extract with Justus von Liebig’s signature on the label, included to differentiate it from possible copies. LEMCO Collectible cards edited by LEMCO. They show containers of the extract with Justus von Liebig’s signature on the label, included to differentiate it from possible copies. |

«The product quickly became famous and entered the rations of armies and adventurers, as we can seen in the Franco-Prussian War» | |

|

The extract of meat, apparently useless in Europe, found justification in South America. Or so thought Giebert, who crossed the Atlantic in order to advice Liebig on the creation of a factory. His boldness was rewarded, although the veteran chemist postponed his approval until he checked the quality of the Uruguay product. So Giebert went back to Villa Independencia, which would later be known as Fray Bentos, and managed to collect enough money to start his enterprise and produce an excellent sample, which he sent to Liebig. Thus was born the Liebig’s Extract of Meat Company (LEMCO), whose product was immediately successful due to its excellent flavour and affordable price, low enough for the emerging European middle class. Less than a decade after that, the Fray Bentos facilities grew to accommodate hundreds of workers who sacrificed over 2,000 heads of cattle a day. The meat obtained underwent a slow cooking process and was later steeped in cold and hot water to reduce 32 kilograms of raw material into just one kilogram of extract. Once packed, it was departed towards Europe from the pier in the Uruguay river, and the product was unloaded in Antwerp, where the company had its storehouses. The entire operation was controlled from the central offices in London, the world financial centre of the time. LEMCO had become a true food industry multinational in just a few years. The ceiling of the company was still very far, though. The sale of new products would allow it to grow exponentially until well into the twentieth century. First, in 1873, they launched Corned Beef Fray Bentos, brined canned beef cooked with vinegar. Later, in 1899, they started selling a cheaper, liquid version of the Liebig extract, named OXO. LEMCO sold more than 200 different items, using every single part of the animal. Fat was used for cooking, skin was turned into leather, tendons were used to produce carpenter’s glue and some bones were the material for household objects, the excrements were used as manure, the guts wrapped sausages and the tongues were a prized delicacy. The company catered to religious taboos as well; in India, they sold lamb extract for Hindu people. The French journalist Jules Huret aptly described the Fray Bentos factory as «the world’s largest kitchen». A «kitchen» that sacrificed millions of animals in its facilities, apart from the work in the other factories of the company in Argentina, Paraguay and Zimbabwe. They were always at the vanguard of technology. The first light bulb in South America was used in the factory, an evidence of the innovation they would also manifest in other fields, such as marketing. LEMCO’s advertising campaigns made history. For decades, they published more than 7,000 collectible cards that were exchanged in the retail outlets, and in 1902 they offered the first promotional present in history, a rattle for kids in exchange for an empty container. They were even pioneers in the sponsorship of sports events, such as the 1908 Olympics celebrated in London, where the marathon athletes received the OXO tonic. |

Mètode London’s famous OXO Tower, on the banks of the Thames, belonged to LEMCO. Mètode London’s famous OXO Tower, on the banks of the Thames, belonged to LEMCO. |

|

Elbetobm Original Corned Beef label from the «Frigorífico Anglo». Elbetobm Original Corned Beef label from the «Frigorífico Anglo». |

«The progressive generalisation of modern refrigerators transformed eating habits and canned meat lost its privileged position» | |

|

Shortly thereafter, World War I would mark the peak of LEMCO’s history. The OXO cubes, which had just replaced the liquid tonic, became one of the main food items in the front. One hundred million of these meat extract cubes were distributed, together with an ingenious carbon heating system – the OXO Trench Heater, which released no smoke so it could be used in the trenches. The Corned Beef Fray Bentos was also popular among the troops. So much so that they used the brand name to refer to something that is well done – just as «O.K.» during the next World War. The germinal extract of the company did not enjoy the same popularity and suffered the prejudice that inhabits every military conflict. The German origin of the Liebig surname could not be hidden, so it was frowned upon by the allies and had to be relegated. The name of the company suffered a similar fate. LEMCO, which hid the name Liebig’s Extract of Meat Company, was substituted by the name of their most successful product, OXO. The de-Germanisation process would conclude with the replacement of the name of «Saladero Liebig» in Uruguay for the more patriotic «Anglo Frigorífico». The name change evidences also the restructuring of the factory during that period. Between 1921 and 1924, an enormous five-storey building was built in Fray Bentos. It was completely refrigerated with a new ammonia compression cooling system and serves as meat storage. It was a revolutionary technological innovation at the time and would give new impetus to the factory, maintaining the company at the top until World War II, where it was, again, essential for the allied military effort. The end of the war, however, marked the start of the decline of the previously lucrative business. The progressive generalisation of modern refrigerators transformed eating habits and canned meat lost its privileged position in favour of fresh or frozen meat. The OXO company managed to adapt and stayed as a food multinational, but their current cubes have little to do with the ones they produced during a good portion of the twentieth century. As with most competitors, modern stock cubes are essentially a mixture of salt and yeast extract, obtained as a residual by-product in beer breweries. Without the need for large quantities of meat, the «Frigorífico Anglo» lost the reason for its existence. Their activity waned gradually and their facilities ceased to be updated. In 1971, it was purchased by the govern of Uruguay, but it closed eight years later. Fray Bentos is today a quiet town with 25,000 inhabitants, many of whom descend from the soldiers who emigrated from seventy different countries to work in the meat industry. Its port, for decades bustling with industrial activity, has been repurposed to serve the interests of tourism. The facilities of the «Frigorífico Anglo» found in this industry their last purpose. The factory is currently the headquarters of the Industrial Revolution Museum, where one can rediscover the past glory of this corner of Uruguay that was once the world’s largest kitchen. |

||

REFERENCES

Alonso, S.; Craciun, M.; De Souza, L. & E. Nisivoccia, 2010. «Frigorífico Anglo». In 5 narrativas, 5 edificios. 12ª Bienal de Arquitectura de Venecia. Montevideo. Available at: http://www.alonso-craciun.net/pdf/publicacion-bienal-venecia.pdf.

Boretto, R. & A. Olveira, 2005. «Carne de Cañón». VII Jornadas Internacionales sobre Patrimonio Industrial. INCUNA. Gijón. Available at: http://www.rionegrotodo.com/patrimoteca/CARNEDECA%D1%D3N.pdf.

Esteban, S. & J. Pérez, 2012. «Extracto de la carne: la invención de un químico». In Pinto, G. & M. Martín (eds.). Enseñanza y divulgación de la química y la física. Garceta. Madrid. Available at: http://quim.iqi.etsii.upm.es/vidacotidiana/EnsenanzayDivulgacion%282012%29.pdf.

Pharo, G. Taking Stock: The OXO Story. Available at:

https://hawkhurstkent.uk/images/hawkhurst/oxo/hawkhurst-oxo-story.pdf

Real Academia Nacional de Farmacia, 2003. Anales de la Real Academia Nacional de Farmacia, 69(4). Available at: http://www.analesranf.com/index.php/aranf/issue/view/64.

Solivérez, C. E., 2012. «Auge y decadencia de la carne conservada». Enciclopedia de Ciencias y Tecnologías en Argentina (ECYT-AR). Available at: http://cyt-ar.com.ar/cyt-ar/images/1/1b/Liebig.pdf.

Verne, J., 1870. Autour de la Lune. Pierre-Jules Hetzel. Paris.