A maverick’s glory in scientific research

Francesc Torrent-Guasp, the physician who revolutionised conventional cardiology

Techno-science currently comprises a complex system of knowledge production and transfer, of artefacts that constantly reshape social practices, with repercussions on people’s daily lives. The chemist, doctor, engineer, economist, or even the artist, are just another component of a complex network where social dynamics, knowledge, culture, technology and customs flow in ever-changing and transforming ways. Scientists, entrepreneurs, publishers, public administration, social demands, marketing… play a vital role –as never before– and determine the subject of investigation and define the final product. This is a far cry from the traditional image of the researcher, scientist, artist or physician as a solitary scholar, who, in their ivory tower and endowed with great intelligence, overwhelming intuition or obsessed with solving a problem, end up lighting the way for humankind, generously and selflessly. Indeed, current techno-science represents an entirely different organisational structure or model.

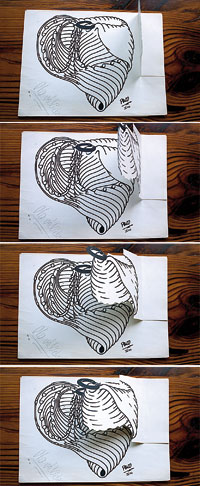

The doctor Francesc Torrent-Guasp studied morphology and physiology of the heart on his own. In 1973, he proposed a new description of the structure of the heart, as a single muscular band. Above, one of the doctor’s hand-drawn pictures from his study, kept by his family at his home in Dénia. / Photo: Ana Ponce & Ivo Rovira

Analysed from the logical viewpoint, like that of Karl Popper and Bertrand Russell, or from the sociology of knowledge –whose foundations were built by Max Weber, Karl Mannheim and Ludwik Fleck– or from the dynamics of change and transformation of knowledge –like Thomas Kuhn–, global twenty-first century techno-science comprises a network of institutions, laboratories, companies, conferences, publications, facilities, techniques, financing methods and industries that render the traditional image of the affable scientist quite unthinkable: science and technology constitute a plural and collective task. The works of Bruno Latour, Steven Woolgar, Steven Shapin, Dominique Pestre, among other analysts of our postmodern globalised world, demonstrate that techno-science currently represents a powerful instrument, the result of institutionalised collective work, in which a host of agents, both public and private, interact, legitimise and reinforce each other. Therefore, when a maverick or an outsider comes unexpectedly to the forefront, they jolt the system of relationships and interactions that legitimise knowledge and its products. Their vision of reality is not so conditioned by the conventions of scientists that are well-integrated in the system, who form a community and share a style of thought and ideas. The system rejects the independent researcher, reacting as dramatically and intensely as a living organism reacts against an external attack. Let us not forget that society is a complex reality, a living organism whose components react to novelty with recognition or rejection, with integration or intolerance.

Torrent-Guasp’s vocation for heart anatomy

Medical historians share the idea that since ancient times the macroscopic anatomy of the human body was constructed little by little from the observation of dead bodies. The most relevant contributions came from Herophilus of Chalcedon and Erasistratus of Cos, both from the School of Alexandria, and from Galen of Pergamum, and were finished off by the anatomists of the Renaissance, Günter von Andernach, Laguna, Colombo, Valverde and others led by Andreas Vesalius. This was a radically morphofunctional anatomy, where the distinction between form and function, between structure and dynamism was meaningless, two sides of one reality. Historians also agree that Vesalian anatomy revolutionised how the body was represented and, in the eighteenth century, topographical or surgical anatomy brought a new perspective to human anatomical forms. In short, for generations the cornerstone of our reasoning has never been questioned: descriptive anatomy is a building block of scientific knowledge; topographic anatomy is a restructuring, while evolutionary anatomy is the definitive understanding of the origin and organisation of anatomical forms. But let us not forget the Cartesian axiom of methodical doubt, according to which disbelief and suspicion are the quintessence of research.

Drawings of the heart, summarising Torrent-Guasp’s hypothesis. Original drawings by the cardiologist from Dénia, signed «Paco». / Photo: Ana Ponce & Ivo Rovira

Francesc Torrent-Guasp (1931-2005) appeared in the scientific arena when he was already a man of experience, having done his own research work –always outside academic and research institutions– on the morphology and physiology of the heart. Born in Gandia in 1931, he studied medicine in Madrid and Salamanca and even as a medical student, back in 1954, he discovered his fervent vocation for anatomy, for his desire to understand organic forms and in particular to understand the part of the body which, since ancient times, has been associated with the expression of life: the heart. For Aristotle this organ was analogous to the generative spirit, while for Galen it was the seat of the sensitive soul. Torrent-Guasp’s obsession was to reconcile anatomy with the logic of heart function, as a pump that draws blood and pumps. The metaphor of «engine pistons» was never far from his mind.

Torrent-Guasp doubted the idea that blood could enter the heart and penetrate the left ventricle alone without being sucked in by an active force. Obsessed by this enigma, at home he made a long phylogenetic revision of the heart of amphibians, apes, hominids, and made an in-depth analysis of the evolution of circular fibres in the hearts of vertebrates, even studying the embryogenesis of the human heart. After two decades of investigation and dissection, of myriad experiments on a variety of animals to solve a single problem, in 1973 he proposed a description of the heart structure as a single muscular band, beginning at the insertion of the pulmonary artery and ending up below the point of exit from the aorta, folding into itself in a helical manner. In accordance with this architecture, in 1997 he went on to advocate cardiac mechanics based on the progressive contraction of the muscular band, consistent with the suction and expulsion of blood, as two active movements of the cardiac muscle.

«The unorthodox work of Francesc Torrent-Guasp played a central role in the rejection of traditional doctrines, so long accepted by cardiologists»

Torrent-Guasp called this the muscle band or ventricular myocardial band, which folded into itself in a helical way. This description provided a new image of the heart, without dual ventricles, but rather a folding of the muscular band, which was wrung out like a cloth along its entire length due to successive contraction. His morpho-functional description of the heart broke with the traditional idea of a systolic movement understood as an active contraction, and a diastolic state understood as passive relaxation, a working model that had never convinced his critical eye. How was it possible for the heart to draw the blood through a simple movement of passive relaxation? For decades he devoted all his energy to proving the fallacy of the traditional model at his home in Dénia, his only research laboratory.

View of Torrent-Guasp’s study at his home in Dénia, where he worked upstairs, showing many pictures and other curious objects that made it a unique environment. / Photo: Ana Ponce & Ivo Rovira

Mixed reactions to his work

Despite his status as a lone researcher whose aim was to resolve a single scientific problem, in 1972 Torrent-Guasp received support from the Juan March research foundation to carry out his experiments. When his hypothesis was released, shortly afterwards, it was met with mixed reactions by the international community. Some criticised him for being speculative and unscientific while others took his ideas onboard and praised his boldness as something fitting of a great researcher. In 1974 he was awarded the Miguel Servetus prize in Geneva and Daniel Streeter incorporated Torrent-Guasp’s ideas in his Handbook of Physiology (1979). Moreover, Torrent-Guasp’s proposed description of the heart soon led to the development of new surgical techniques. Probably, cardiac surgeons were the most appreciative of his proposal and of the practical applications it facilitated. In fact, the surgeon Buckberg suggested the eponym pacopexia or pacopexy in honour of «Paco» (short for Francesc) Torrent-Guasp, to describe a surgical technique for ventricular remodelling, based on Torrent-Guasp’s description of mitral annular systolic contraction, and leading to Donald Ross’s design of valves with a ring. In 1996 Torrent-Guasp was awarded the gold medal by the Spanish Cardiology Society and in 2001 the Journal of the American Association of Thoracic Surgeons (AATS) dedicated a special issue to his work, entitled Seminars in Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery.

«For decades he devoted all his energy to proving the fallacy of the traditional model at his home in Dénia»

Although our doctor disseminated his ideas through conferences, and rarely through international scientific journals, his new vision of heart structure and functioning caused a strong impact in science worldwide. He also began collaborating with Francesc Carreras in the cardiac imaging unit of the Saint Pau Hospital in Barcelona. In 2002 the authoritative US National Institutes of Health organised a multidisciplinary international seminar inviting around thirty European and US scientists to discuss Torrent-Guasp’s ideas. Support for his ideas arrived in the form of analogical and digital images, provided by new imaging technologies applied to medical research, which further consolidated the Valencian doctor’s ideas. Soon he was organising international courses on cardiac structure and function at his home in Dénia, with the collaboration and participation of Japanese and American specialists.

Final recognition

Paco Torrent-Guasp died suddenly after delivering the closing conference of a meeting on electrophysiology and arrhythmia, held in Madrid in 2005. He gave his lecture sitting in a wheelchair, suffering from sciatic pain, but was happy to explain to electrophysiologists how the heart’s contraction mechanism begins in the myocardium of the right ventricular outflow tract and ends in the left ventricular apex. This dynamic action was christened «piston cardiology» by Pedro Zarco, of the Royal Academia of Medicine.

The heart dynamics postulated by Torrent-Guasp included three movements of the muscle fibres: a longitudinal shortening, circumferential narrowing and a twisting spiral motion, like wringing out a cloth, a metaphor used in the seventeenth century by the British anatomist Richard Lower. In a paper published in the Circulation Research journal, Brecher marked two milestones in proving that active filling of the heart takes place: Erasistratus, an Alexandrian anatomist from the third century BC, and Torrent-Guasp. According to Juan Cosín from the Hospital La Fe Research Centre in Valencia, Torrent-Guasp’s ideas are supported by consistent experiments; however, at the same time, they question the fundamentals of electrocardiography in relation to polarisation processes, action and relaxation, difficult to accept.

Thus, the unorthodox work of Francesc Torrent-Guasp played a central role in the rejection of traditional doctrines, so long accepted by cardiologists. He met with rejection that led to loneliness and resistance, but so too with recognition of the importance of his stubborn work and his imagination, spark of scientific research.