Under a white sky

Elizabeth Kolbert

Spanish translation by Lluís Riera. Crítica. Barcelona, 2021. 215 pages

Then God said, «Let us make humankind in our image, according to our likeness; and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the birds of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the wild animals of the earth, and over every creeping thing that creeps upon the earth». These are words from Genesis (1:26), and it seems as if mankind, both believers and non-believers, took them literally. Thus, the human species, for as long as it has existed, has not stopped exploiting the resources of our planet, right up to the industrial revolution, which accelerated it all: the unchecked increase in CO2 emissions, global warming, and global change, including the biodiversity crisis. Since the invention of the steam engine, the global average temperature has risen by 1.1ºC. It seems that reaching 2°C could be catastrophic, and it has been established that the increase should be limited to 1.5°C at most.

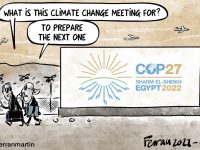

The most obvious solution is already known: reducing CO2 emissions to the point of practically eliminating them. But there are at least two problems. One is that they are very difficult to reduce, both in, say, rich countries, which are reluctant to change their model, and in poor countries, which aspire to the rich countries’ model. The other problem is that even if we were to stop them altogether immediately, the momentum of the current situation seems likely to push us over the dreaded 2°C threshold.

In her book Under a white sky, Elizabeth Kolbert reminds us of these facts. She then discusses a number of solutions, tested in the past and proposed for the future, to tackle global change and the biodiversity crisis. Some of the tested solutions proved to be worse than the problem. This is the case of importing predators to control certain pests, which have in turn become worse pests, which could be controlled by importing another predator… Or efforts to limit the spread of exotic freshwater fish (which is predicted to be disastrous) by electrifying stretches of rivers and canals….

But global warming continues, and radical solutions must be devised for the time when there are no others left. In the final part of the book, Kolbert talks about negative carbon emissions, i.e., removing CO2 from the atmosphere, for example by capturing it and literally turning it into stone. An expensive solution, but technically feasible. The author also explains, at the limit of creative solutions, the strategy of reducing solar radiation by scattering reflective particles (calcium carbonate, for example) in the stratosphere, so that less radiation reaches the sky. The colour of the sky would no longer be blue, it would be white, but perhaps we would manage to cool the planet.

It is worth knowing that these risky ideas exist, because one never knows. However, we must remember the mistakes we have made in past interventions in nature, and at the same time be aware that, if we apply global solutions, the consequences of getting it wrong will also be on a planetary scale. It will not be easy to make decisions on these new strategies. Kolbert explains them very well, but does not take sides. He probably leaves that to the reader. And he is right to do so.