Interview with Michel Maffesoli

«Our century will see the comeback of esoteric and mystical forms»

Professor of Sociology at René Descartes University – Sorbonne, Paris

Michel Maffesoli (Graissessac, France – 1944) leaves no one indifferent. Accustomed to stirring up controversy in his country, the sociologist of postmodernity known for spreading the concept of «urban tribes» has just published Homo eroticus. Des communions émotionnelles (2012), in which he discusses his theory about the prevalence of emotions and emotiveness in our society. A postmodern society –the most frequently repeated words in the interview– of which the sociologist considers the former French president Nicolas Sarkozy to be an example. This was stressed in his book entitled Sarkologies. Pourquoi tant de haine(s)? (Sarkologies. Why so much hatred?), published during the last French presidential election, from whose results we could infer that the French are still reluctant to fully enter into the postmodern era.

His relationship with power has raised qualms among French sociologists, but one of the most controversial episodes concerned an academic thesis. In 2001, Michel Maffesoli directed the thesis of a famous astrologer, Élizabeth Teissier, which earned the censure of many French sociologists as well as of scientists, who saw this work as a means of supporting astrology by academia. Indeed, due to this controversy, a group of sociologists and scientists (astrophysicists, physicists and historians of science) analysed the academic work, which they classified as a «manifesto of astrology» and «eulogy of astrological “science” ». Scientists thought this disquieting episode might be a prelude to introducing astrology into the university syllabus. Something the sociologist has always denied.

«Our society is witnessing a return to syncretism, the melding of astrology and pseudoscience. I am not saying that it is right or wrong, my position is one of absolute axiological neutrality»

Professor Maffesoli recently participated in an international symposium organised by Professor Domingo Pujante at the University of Valencia, entitled «Diverciudades: Visiones urbanas de lo cotidiano» (Fun-cities: Visions of the everyday urban) and he kindly agreed to give an interview at the central Ruzafa hotel where he was staying, and did not object to discussing this issue, or others related to his vision of our society today.

In his characteristic style, sporting an impeccable blue suit and matching bow tie, the Sorbonne professor of sociology is completely at ease, and patiently collaborates for the photo shoot, posing as the photographer requests. He is obviously used to interacting with the press. On sitting down, his trousers hitch up to reveal red socks matching his shoelaces. «They are cardinal’s socks», he says jokingly with the hint of a smile that does not vanish throughout the interview.

You have popularised the idea of «urban tribes», where does this idea that humans need to belong to a group stem from? Is it a biological need?

The tribe is a metaphor to show the step we are taking from modernity to postmodernity. It is the transition from a more rational concept of living together, towards a more emotional one. Large institutions characterised rational modernity, but now we have a fragmented social body that can be more closely linked with biology and is more reminiscent of our human animal essence. Among our instincts is the sense of belonging, which makes us seek proximity. For me, the main trend in our society is the one reminding us of the notion of our animal nature.

Photo: Miguel Lorenzo

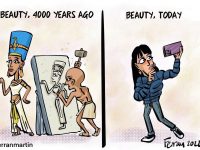

In your writings, you compare the icons of our society with the totems of primitive tribes. Do we need to have models to emulate or idolise?

Beyond the myth of progress that has characterised rational modernity, there is a return to the need for images. And yes, we need these icons. To some extent, modernity had banished these images, because they do not let the brain work properly. But suddenly, the images are rife on television, in advertising, video games… and we find a return to the icons, just like in primitive societies. This is a topic I have discussed in my book on iconologies: Iconologies. Nos idol@tries postmodernes (2008) (Our Post-modern Idolatries), where I talk about modern icons such as Harry Potter or football players like Zidane.

But what do we find in these icons? Why are they important to us?

Icons are a crystallisation –as the French novelist Stendhal would put it– of our ghosts. That is, icons are a caricature of the unconscious desires people have. And that reminds us that we need totems, around which primitive tribes gathered. And now, postmodern tribes according to their desires –be they sexual, religious, athletic or musical– also gather around a sexual, religious, athletic or musical totem. These are the totems, and they have an aggregate function.

Photo: Miguel Lorenzo

Some anthropologists and evolutionary biologists understand religion as an adaptive trait of human beings, which has allowed us to evolve as a society through group cohesion. What do you think of this evolutionary view of society?

Personally I am not entirely sure that evolution is linear. It is what I consider the false myth of progress. The evolutionary view tells us that humanity has progressed from point A –barbarism– to point B –absolute civilisation–. And yet we see a return to past tendencies. Tribes are archaic, they belong to primitive societies. In terms of social evolution, we might think that we had left behind these tribes precisely through large institutions created in the nineteenth century. But I demonstrated that there is a return to tribes. I like to illustrate it with the image of a spiral. There is not just an evolution, but also a regression. I think the word ingression is much more interesting, because we are a tribe, but with technologies like the Internet. We are returning to things we lived in the past, but with the addition of technological development. So I do not take an evolutionary stance in that respect.

In politics, you take Sarkozy as an example of postmodern man, why?

I found it amusing to highlight Sarkozy as a postmodern politician because he represents the eternal child. He has this playful, non rational aspect, which makes him accentuate the most emotional aspects.

I don’t know whether you are familiar with Spanish politicians, do you find a similar figure in this respect?

The truth is I do not know the real situation in Spain, I might say something silly.

What about Europe?

Italy’s Berlusconi would fit the same profile. A mixture of brain and passion. Also Lula in Brazil or Chavez in Venezuela. There is a return to the emotional facet. But the truth is that I do not know what it is like in Spain. For instance, I think Zapatero represents the opposite to postmodern man; he could be the example of rationality, the equivalent to Hollande in France.

«I am not entirely sure that evolution is linear. We see a return to past trends. Tribes are archaic, they belong to primitive societies»

You suggest this «emotionality» is a feature of postmodernity, could we say that we are less rational today?

In French there are two interesting terms. One is the social contract, the term coined by Jean-Jacques Rousseau, which has characterised the way we live in society. A social contract involves an agreement between two rational people to make policy. And now there is a shift from contract to pact. A pact is much more emotional. A contract implies something long-term, while a pact is pure passion. So yes, I think there is a return to collective emotions in all areas. But this does not imply a denial of reason. I wrote a book called Éloge de la raison sensible (1996) (In Praise of Sensible Reason), which, although apparently an oxymoron, is what I want to show: how reason and passion are mixed. The affections and feelings take on an increasingly important role. And for me this is what characterises postmodernity.

So, is it in this context that you speak of Homo eroticus in your latest book?

Yes, in this book I return to the idea that social eroticism exists. For me, eroticism is not just sexual, but rather it has to do with good vibes. The term to describe this is «in tune», there is a sports or religious grouping… and in this fusion we see that the main aspect is shared emotions. I think the same happens in Spain as in France, where every occasion is used to generate collective vibrations.

Photo: Miguel Lorenzo

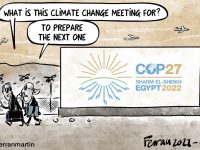

What place does science hold within this more emotional and less rational society?

Postmodernity is not a denial of reason, but rather it is complementary to reason and the senses, what I said: sensible reason. And from this perspective, science and technology have their place. I wrote a book showing that, thanks to technology and to scientific applications, we are witnessing a new enchantment. Science and modern technology have re-enchanted the world. There is a place, obviously, for science in our society from the perspective of this enchantment or new fascination.

In a 2009 interview you stated that a sociologist’s work is not just in books, but also in bars. Did you want to say that the university has moved away from society?

Yes, and for me it is one of the problems of the university. University academic-based knowledge has been abstracted, it has become disconnected from reality, and hence this response regarding «books and bars». We must find a balance between academic thinking, which is important, and at the same time the ability to «smell» society. Smell the bar, the market, the street… which for us is the field of observation. Let us not forget that the university was founded in the Middle Ages, and is organically rooted in the life of that epoch. But since then, little by little, it has become more rational, too abstract, and therefore I believe there is a need for knowledge to dig new roots in current daily life. At the Sorbonne I run a research centre –founded over thirty years ago– on everyday life in the present time, so for me everyday life is very important.

«Postmodernity is not a denial of reason, but rather it is complementary to reason and the senses. And from this perspective, science and technology have their place»

Is that why you directed a dissertation on astrology in 2001? It sparked a great debate at universities and in French academic circles, didn’t it?

Quite so, a huge controversy arose. I have directed three dissertations on astrology, but one had great impact because the author was a very popular astrologer –well known publically– and this is what sparked so much controversy. At my Centre, we are atypical in that we study subjects that universities do not touch on. For example, I was the first person to direct a thesis on homosexuality, which was not a trendy topic at the time. But I have also directed dissertations about restaurants, about partner-swapping parties… I have tackled subjects that conventional science is afraid to analyse. But also within the realm of interpretive sociology, a social fact can become a sociological fact. For me, sheer existence is enough, and from the moment something exists, it must be studied. Fifty percent of French people consult the horoscope in the press, and that is enough for me to base my argument on, because this constitutes a social reality. And finally, if there is someone involved in the issue in question who wants to study it, as was the case with this astrologer. For me there is no such thing as absolute objectivity. For example, a priest can do a thesis on the Church or a political activist can do one about politics. And likewise, an astrologer can write a dissertation on astrology. There was a lot of controversy because French intellectuals –and sociologists in particular– always consider things in a moral light. I mean, they think how the world should be, while my position is that the world is. Personally, I have no interest in astrology, but at the same time I cannot deny that it is a social phenomenon.

«Fifty percent of French people consult the horoscope in the press, and that is enough for me to base my argument on, because this constitutes a social reality»

One of the things you were accused of was having let astrology into the university syllabus.

No, absolutely not. It was a study of astrology. Nobody actually read the dissertation or knows that its title was: The Epistemological Status of Astrology through Rejection / Fascination Ambivalence in Postmodern Societies. That is, how the media, in particular newspapers, are attracted by astrology. This was the thesis topic. The goal was not to teach astrology at the Sorbonne.

Photo: Miguel Lorenzo

But surely the dissertation, and specifically one of the annexes, maintained how stars influence people.

One of the annexes, and thus peripheral to the thesis itself, gave a description of the astrological signs. But the dissertation was not about that, but rather about the media’s fascination with astrology.

Does this fascination with astrology –and pseudoscience in general– have any connection with the growing emotional undercurrent that defines our age?

Yes, we could say that we are witnessing a return to syncretism in our society, which could be the melding of astrology, American New Age, pseudoscience in its many forms… Again I am not saying that it is right or wrong, my position is one of absolute axiological neutrality, but we observe and analyse from the sociological standpoint. But it is true that there is a growing need for sacredness, for religion, in our society. Our century will see many of these somewhat mystical or esoteric forms returning. And we must analyse this, it is no good denying that these phenomena don’t exist. And this is the goal of sociology. Any social fact can become a sociological fact.

The Proust questionnaire

The Proust Questionnaire is a personality test, which became famous owing to the responses given by the French writer Marcel Proust. Mètode thought it would be interesting to reveal the personal facet of our interviewee.

Your favourite virtue: Tolerance.

Your favourite quality in a man: Lucidity.

Your favourite quality in a woman: There’s no difference, lucidity too.

Your favourite occupation: Reading.

Your chief characteristic: Courage.

Your idea of happiness: The good life.

Your idea of misery: The loss of loved ones.

Your favourite colour: Blue.

Your favourite flower: Fleur de lis, the lily.

If not yourself, who would you be? A cardinal [he laughs].

Where would you like to live? I’m happy in Paris [he laughs].

Your favourite prose authors: The German philosopher Heidegger.

Your favourite poets: Nineteenth century poets, Victor Hugo.

Your favourite painters and composers: Similar, I really like nineteenth-century painting, somewhat classical painters.

Your heroes in real life: The people would be my hero.

Your heroines in real life: The same, society.

Your heroes in fiction: Ulysses.

Your heroines in fiction: She would also be from mythology, Venus.

Your favourite food and drink: [He laughs.] I have so many. Let’s say my favourite food is a French dish called cassoulet, from Toulouse … and I love white wine.

Your favourite names: Hélène.

What pet do you dislike? [Thinking aloud.] I have cats, so I could say I don’t like dogs … I couldn’t really say…

What characters in history do you most dislike? Dictators, Stalin.

What is your present state of mind? Optimistic.

For what fault have you most toleration? Weakness.

What is your favourite motto? Always the explorer.