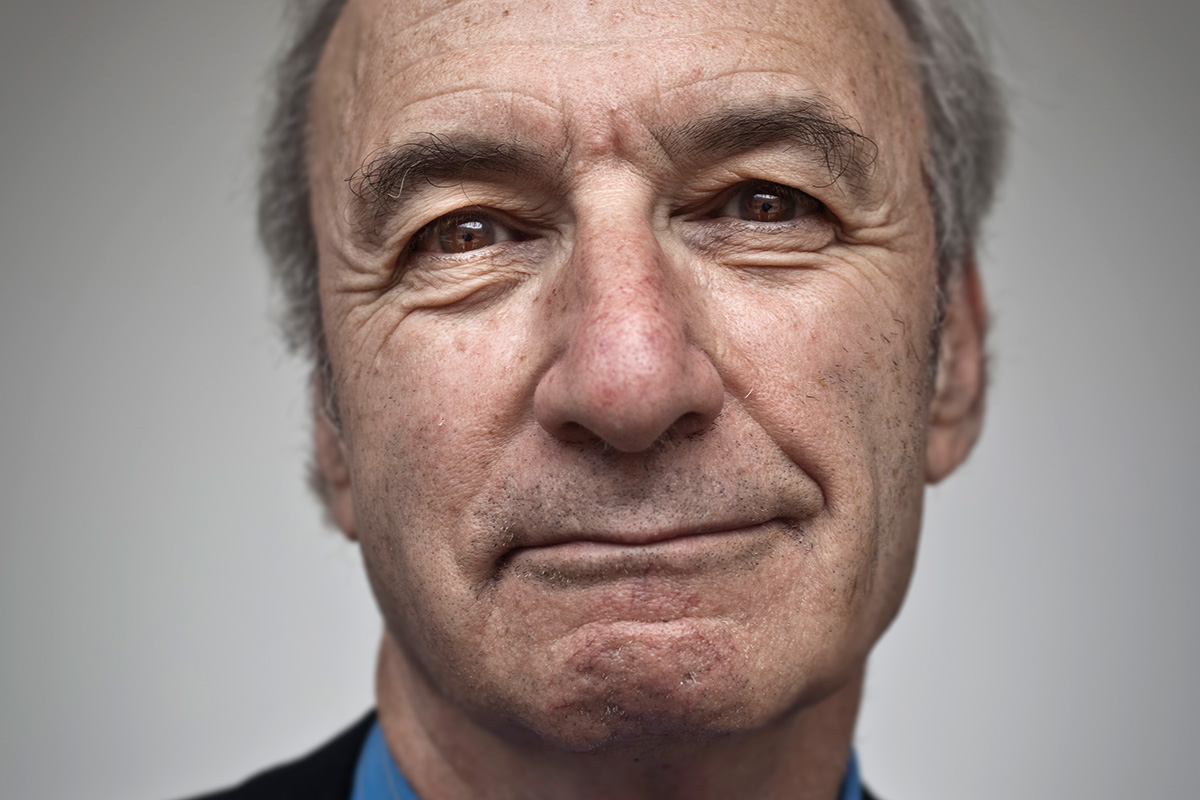

© M. Lorenzo

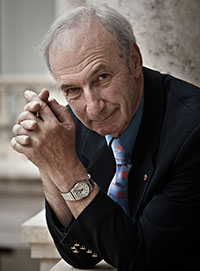

Thomas Glick is a professor of Medieval History at the University of Boston, and holds an honorary degree by the University of Valencia. For more than forty years, he has been coming to Spain in order to carry out researches on the reception of scientific ideas, mainly Darwinism, psychoanalysis and the theory of relativity. In the last years, he has devoted himself to the study of the history if technology in Valencia, especially regarding irrigation, and has become a tireless defender of the Valencian farmland. He is a member of prestigious institutions, such as the Reial Acadèmia de Bones Lletres de Barcelona (Royal Academy of Belles Lettres of Barcelona) and the Spanish Society of History of Science, among others. His work as a Hispanist has been recognised with awards like the international prize Geocrítica (2004), the research Serra d’Or Critics Prize in 1987 and the Academic medal of the Mexican Society of the History of Science.

He came to our interview wearing a cowboy hat, keeping his promise of being easily recognisable. «Nobody wears a hat anymore», he complains. The thing is that Glick, as any historian, can’t help feeling a longing for the past.

Many people finish their History studies thinking that the only way to make a living out of it is teaching. In the beginning, was it very difficult for you to find ways for funding your projects?

No, it was easy. I don’t think it is easy nowadays, but back then it was. When I came back to the USA from Barcelona, the government would pay students for studying unusual languages asking for nothing in return. I was paid for two years. After that, I was given another grant so as to come here to carry out my researches. This happened in the middle of a period of expansion of the university system in the USA. They were constantly creating new jobs. This ended around 1972 or 1973. Universities were expanding and money was available. I remember that, one day, in the University of Texas, where I had my first post in the Institute of Latin-American Studies, its director started shouting, “Does anybody need money?”

© M. Lorenzo

Regarding Valencia, in the last interview held with Mètode, you said that its farmlands had only fifteen years left. Seven years have passed since then. Has its situation improved?

You can check it with your own eyes. What is happening is terrible. There is no awareness among the general public of the rarity of peri urban farmlands. In Damascus, farmlands are virtually dead; in Palermo there was a farmland that no longer exists. To me it is like witnessing the extinction of a species. In this case, this species is a kind of human settlement historically important, and it is a pity that not even an area has been preserved as a National Historic Area, for instance.

The reasons for its preservation are historical, then?

Traditional irrigation channels have been demonised as inefficient —they sell water at a loss, etc. But something curious happens here, the dominant idea among land labourers is that shallow irrigation channels have to be eliminated, and pipe water and use controlled drip irrigation. There are two problems here. The first one is that this interferes with the natural refill of water resources, which is done thanks to the filtration of water in these irrigation fields. The second, is related to evapotranspiration. Water evaporates, which makes raining possible; and the scientist Millán Millán has demonstrated that in the last decades, the moment areas with functional irrigation systems are abandoned, due to the expansion of the cities or to the desiccation of marshes, the result is less rain. This is counterproductive. If we go on with the piping, rain will decrease even more and will fall on different areas. It is a disaster. Maybe it is too late for the Valencian farmlands. By the Xuquer’s riverbanks, piping was started having no guarantees of an increment in the production, and at a great cost. On the contrary, keeping the traditional irrigation channels is cheap. Who benefits from this?

Why do they do it, then?

Because it is in vogue. They have the idea that drip irrigation is more efficient, and maybe this is the case, but it depends on how you define it. Perhaps, in the case of aquatic plants, but with less rain and less refills? It makes no sense.