According to legend, King Solomon possessed a magic seal ring that endowed him with the ability to speak to animals, which made him wise and powerful. As it turns out, fascination for animal behaviour is inherent to human nature. Animals have been feared and admired, sometimes despised, sometimes worshiped, and remained indifferent to no human culture. Since our very own origins as humans, the observation of animal behaviour has been fundamental to our existence; for example in allowing us to develop better hunting and defensive techniques. Some experts go as far as to hypothesize that evolution has ingrained our minds with a tendency to interpret animal behaviour, making us all believe we are «natural» experts in animal behaviour (we’ve all heard it: «my dog does this and that, because of this and that»).

But, despite common lore, behaviour is arguably the most complex and variable of biological traits, as is the job of studying it. An animal’s behaviour reflects a complex interaction between its genetic, physiological and morphological levels, as well as between these and the environment in which it develops. To one degree or the other, a comprehensive understanding of animal behaviour demands an integration of these levels of biological organization. Furthermore, behaviour is the first and foremost trait on which selection acts (probably because it is also the most plastic), and its central importance as a driver of adaptation is becoming increasingly clear.

From a more practical point of view, understanding animal behaviour is vital to understand us as humans. As we will (hopefully) illustrate in this section, the study of animal behaviour is helping us understand what makes us human (and what doesn’t) by enlightening questions we not long ago thought were inscrutable to biology, such as our sense of beauty, our moral, our mathematical abilities, and «diseases» such as obesity or anxiety.

«Fascination for animal behaviour is inherent to human nature. Animals have been feared and admired, sometimes despised, sometimes worshiped»

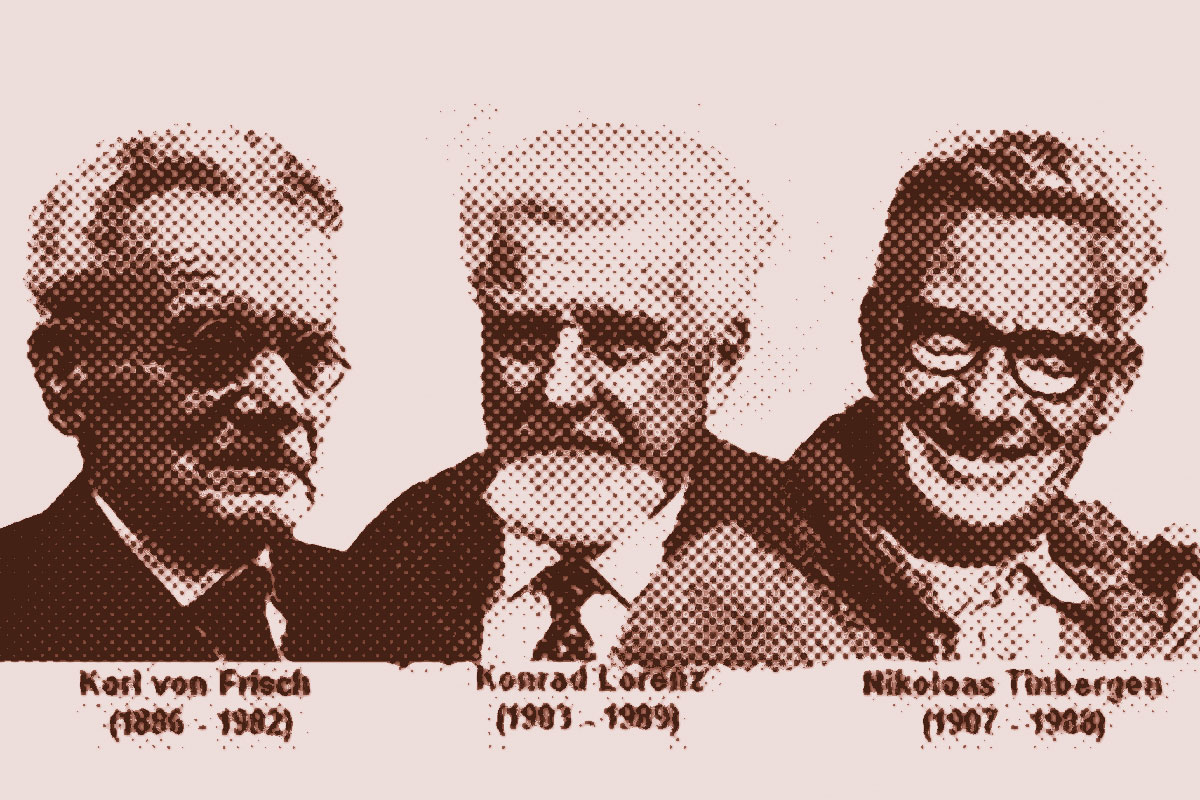

In 1973, Niko Tinbergen, Konrad Lorenz and Karl von Frisch were awarded one of the most unexpected (and deserved) Nobel prizes as co-funders of modern Ethology, thereby marking the coming of age of Animal Behaviour as a modern biological science. We’ve come a long way since then. The modern Ethologist is, in many respects, far from the romantic image of a dusty ruffle-haired Niko in muddy field boots and binoculars in hand, and much nearer to a scientist with fairly specialized yet interdisciplinary studies and skills in a range of sophisticated analytical techniques. In other respects, the modern Ethologist is (fortunately) still Tinbergian in essence, sharing something of the utmost importance with the fable of King Solomon’s ring: the first steps in any serious approach to the study of animal behaviour are tread by observing animals in a natural environment, the only true source of inspiration to ask the correct questions to unforeseen answers. It is perhaps due to this naturalistic marrow that Ethology is still too often despised as a softy among its more senior fellow sciences, but it is also this which endows it with a most unique beauty.

How and why did evolution bring along such awesome diversity of movements and colours, such unimaginable array of ways to perceive, think and act, as those showcased by the «entangled bank» of species that dwell in our planet? How and why do aphids and ants cooperate, does the nightingale sing, or did consciousness evolve? Few scientific endeavours appear as fascinating and puzzling. If you care to join us, from here on we will devote this section to explore its paths.