If we turn our gaze on the past of medicine we will immediately see how medical diagnoses –the terms identifying illnesses– are arbitrary and change over time. After all, diagnoses are just conceptual categories identifying similar processes; we should not mix them with natural realities. The names of illnesses contain concepts created from symptoms and signs of lesion, of injury, of happenstance factors or evolution of processes.

In the middle of the 20th century, psychiatry manuals contained very different diagnosis criteria, depending on the psychopathological orientation of the author. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), first published in 1952, is the reference psychiatry manual.

Even if this could very well be applied to any pattern of illness, the conventionalism seems more obvious in the field of mental illness. Evidently, there can be no science without negotiated agreements such as naming, nomenclature, terminology and taxonomy. Otherwise polysemy, synonymy and neologisms would make science and communication between scientists impossible. A certain amount of lexical order is essential for communication.

In the field of psychiatry, naming of mental disorders stands as a historical problem coming from very diverse and unspecific traditional conceptions and terminology (insanity, mania, moral insanity…) and also the great variety of approaches that psychiatry and psychology developed to deal with the study and interpretation of mental illness. Neurobiology, sociogenic, behavioural and culturalist doctrines, rational thought or unconscious psyche conceptions turned categories of mental illness into complicated, heterogeneous territory, where it is difficult to get to an agreement. Adequate nosology rules to define illnesses using anatomical pathology, pathophysiology or aetiology, among others, were not applicable in this case.

In the middle of the 20th century, psychiatry manuals contained very different diagnosis criteria, depending on the psychopathological orientation of the author. In order to advance with an agreement and standardize psychiatric diagnosis, in 1952 the American Psychiatric Association (APA) published for the first time the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), in which mental disorders were grouped in less than one hundred descriptors from clinical tradition with influence from other fields such as psychoanalysis. Because of the initiative, as well as the international influence of the APA, the DSM turned into a model, and a source of controversy. The second edition, or DSM-II, was edited in 1968 and had only changes from the previous version, but the 1980 and 1994 editions marked a new era, with a stronger focus on casuistry that multiplied the number of disorders spectacularly. In fact, the DSM-IV currently lists 297 illnesses grouped in big categories that serve as a model for the diagnosis of individual patients, mark the starting point for epidemiological studies and the clinical basis for the research of new drugs to treat the almost 300 illnesses: antidepressants, tranquilizers, antipsychotics…

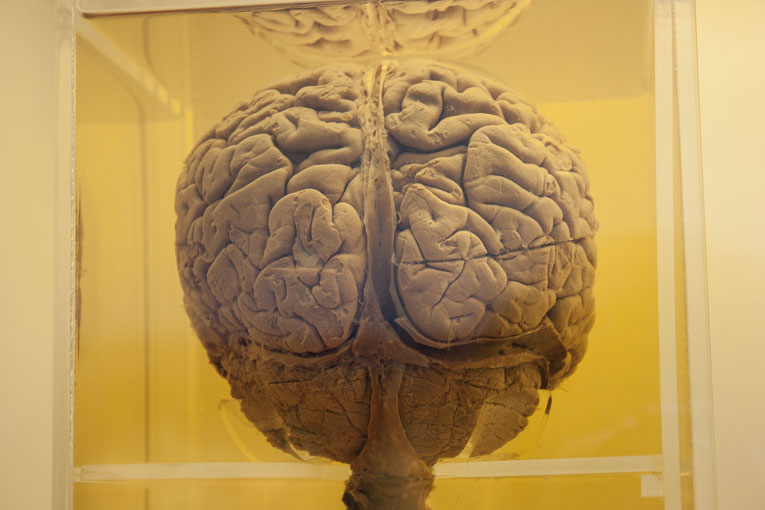

While I write this article, in late May, the APA Meeting in San Francisco is being held, and they will pass an updated edition of the list of mental illnesses: the DSM-5. The preliminary and provisional version has been available online for a couple of years now in order to gather suggestions. The process leading to the current proposal started approximately 10 years ago with the creation of thirteen workgroups made up of professionals from many countries. The present proposal modifies the previous one by adding the use of new diagnostic technologies through brain imaging, as well as genetics studies. It allegedly cost APA around twenty million euros.

«In the field of psychiatry, naming of mental disorders stands as a historical problem coming from very diverse and unspecific traditional conceptions and terminology»

However, the proposal aroused controversy and even opposition from the director of the previous one –DSM-IV–, Allen Frances, and the explicit rejection of the North-Anerican National Institute of Mental Health, the biggest funder in the world for research on mental health. In addition, an anti-DSM collective was created in France three years ago in the psychoanalysis field. Such overwhelming criticism follows three main points: firstly, there is an attack against the tendency to unify and standardize in manuals like the DSM; secondly, it is censored for serving the economic interests of the health industry (pharmaceutical and diagnose industry…), who benefit from the specificity of new mental disorders with new specific remedies; and thirdly, it is thought to medicalize human conduct, helping fabricate new mental illnesses.

Social and political use –not only clinical– of the DSM is very diverse, and in some countries such as the USA or Australia, the DSM manual is a determinant model for the approval of public funding of certain treatments; it also provides expert report criteria for litigation and is a powerful argument in insurance companies assessments. As you may see, there is great controversy, and consensus –the only fundament of science– seems impossible for the moment in this key issue. We have walked a long way. We have moved from obsession to OCD –Obsessive Compulsive Disorder–, from euphoria to mania, from sadness through melancholy to depression, from agitation to hyperactivity disorder, from discomfort to post-vacation blues, from tiredness to weakness… The Quebec philosopher J. C. St. Onge recently published a book devoted to questioning the medicalizing trend that brings the most common of human situations to the field of pathology. There is a lot written on the matter, but this book is named Tous fous? (“Everyone Insane?”). And it is not a simple pun. Beware!