Philip II of Spain was instructed in humanism, was an Erasmus reader and a loved magic and occultism books. He had a soft spot for architecture and geometry, he knew the works of Dürer and Vitruvius, and Pico della Mirandola. In his library, you could find Copernicus’ De revolutionibus, Marsilio Ficino’s Corpus Hermeticum, Pliny’s Natural History, Agricola’s De re metallica and hundreds of books on magic, Hermeticism, and Kabbalistic astrology, which «became necessary to appoint a special censor to purge the El Escorial library, in order to the Inquisition at a distance in 1585».

However, Philip II’s interest in science was not only due to his frame of mind. According to J.A. Maravall, it must be analyzed considering the role of royal power in the organization of science in the sixteenth century. Philip II collected scientific instruments, although the inventory was lost in the conflagration of 1671. He had a collection of a hundred and fifty astrolabes and he was inclined to alchemy –the procedures to obtain silver and gold. In the Monastery de El Escorial pharmacy, distillation techniques were applied to obtain essences, oils, magisteria, tinctures, solutions, coagulations and salts for medicinal uses amongst many others.

«The Monastery of El Escorial shows one of the first political conceptions of science as an instrument of control and power»

He was also fond of natural history. Ever since his youth, he was liked animals, botany and cartography. By Philip II’s initiative, the first botanical gardens in Aranjuez, Casa de Campo and El Escorial were created, following the advice of humanist and physician Andrés Laguna. One of its applications was the cultivation of medicinal plants. Joan Plaza, Professor of Herbs at the University of Valencia, was one of the main suppliers of botanical species and birds from the Albufera to the royal gardens. His successor, Jaume H. Pomar, continued the collaboration and received an Atlas of Natural History preserved in the Historical Library of the University of Valencia in appreciation.

Philip II organized the first scientific expedition to the New World led by Francisco Hernández, who was an Erasmist, Doctor of the Guadalupe Hospitals and Director of their botanical garden. The aim was to study the natural history of New Spain and the Viceroyalty of Peru. Unfortunately, many materials of the Hernández expedition such as sheets and drawings disappeared after a conflagration in 1671. They were not printed and we only have a reduced version published years later in Italy.

Philip II’s interest in science was not only due to his frame of mind. It must be analyzed considering the role of royal power in the organization of science in the sixteenth century. Philip II, 1551. Oil on canvas, 111 x 193 cm. / Museo Nacional del Prado

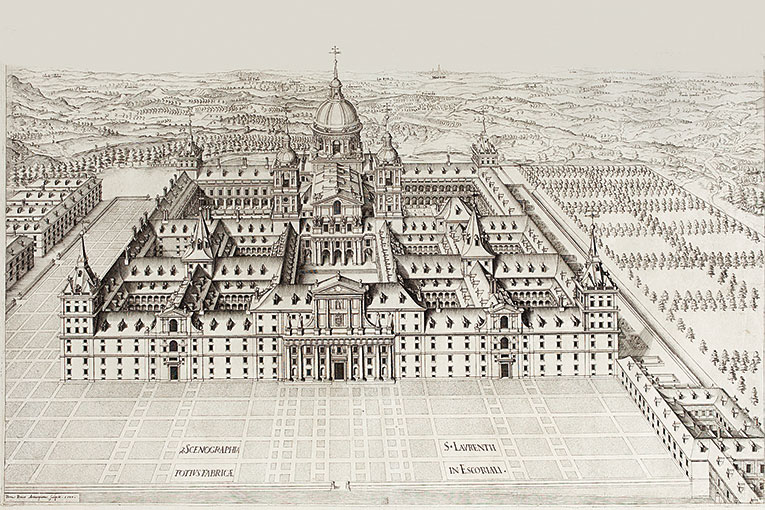

EL ESCORIAL, ARCHETYPE AND SEDIMENT OF RENAISSANCE MEDICINE

The Library wanted to be a synthesis of encyclopedic knowledge and the Monastery was supposed to be a setting for scientific practice with hospitals, pharmacy and botanical gardens. At Páez de Castro’s Memorial, he suggested the library rooms to be filled with sea charts, geographical maps and scientific inventions. The idea of gathering all the wisdom in the Library took shape after transferring monastic libraries, buying books to European printers, several donations from scholars and humanists or the confiscation of private noble libraries. Benito Arias Montano, one of the key figures in the process of putting the Library together, made a first inventory of books. Arias Montano had lived in Antwerp between 1568 and 1575 and had lived among the main focuses of European science. He kept a close relationship with Frisius and Mercator, with printer Plantin and with botanist Carolus Clusius. He sent many astrological and geographical measuring instruments from the Netherlands to Spain, and gave Philip II Clusius’ Index Plantarum and Ortelius’ Theatrum Orbis. After making a stop in Rome, he settled in Spain and due to his influence, Francisco Arceo’s surgery book and Simón Tovar’s drug compound book were printed in Antwerp. Arias Montano was the intellectual link between the European scientific humanism and El Escorial. Among the manuscripts of the Library of El Escorial, a Citopeya or philosopher’s stone was found. It was a sixteenth-century codex that began with a treaty by Stephen of Alexandria about the art of making gold followed by 33 treaties on alchemy. There were about 130 Arabic manuscripts, the works of Averroes amongst them; hundreds of medical manuscripts and works by Ramon Llull and Arnau de Vilanova.

Arias Montano, Doctor Francisco Vallés and Ambrosio de Morales advised Philip II on the scientific activities of El Escorial and organizing its library. Leonardo Fioravanti, Bolognese physician of the viceroy of Naples, carried out chemical experiments. During his stay in Spain between 1576 and 1577, it is said that he was the main Paracelsist linked to the activity in the pharmacy. Diego de Santiago also worked in the pharmacy of the monastery.

Philip II wanted to create a great centre of knowledge in El Escorial. His support of science and technology is one of the first political initiatives taken by the royal power, as well as his cousin Rudolf II did in Prague. The Monastery of El Escorial shows one of the first political conceptions of science as an instrument of control and power.