Contrary to what happens with literature, we do not often read the classics of science; time is limited and science advances by leaps and bounds. We already know what ancient scientists achieved through the distillation offered to us in the introductions of textbooks and digital encyclopaedias. But by taking this shortcut, we miss out on a world of ideas full of rich nuances, a loss that very often limits and narrows the horizons of thought.

Among the forgotten people of science is Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, whose scientific achievements beyond his failed proposal of evolution I have already discussed in this section. Le chevalier de Lamarck died poor, blind and forgotten, and has been reduced to a story about giraffes that has to be repeated every time someone tries to explain his ideas about the process of evolution. In his Zoological philosophy, Lamarck briefly cites the example of the necks of these animals as one of a long series of cases in which he tries to convince the reader of the proof of his zoological principle, according to which the organisation of animals undergoes modifications produced by the influence of the circumstances of their habitation and of acquired habits. By a curious circumstance of historical narrowness, we always read the same example, when in fact Jean-Baptiste was careful to provide a varied range of zoological histories. Varied and sometimes, with today’s knowledge, delirious.

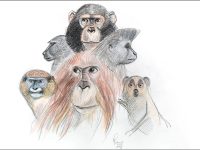

It is worth knowing the other examples that Lamarck gives throughout his magnum opus to explain the structure of animals based on their «habits». There are truly marvellous and imaginative explanations for the feathers of birds, the boneless, cartilage-free body of octopuses, the radial structure of sea urchins, the shape of flatfish such as turbot, the strange hopping gait of kangaroos, or even the stomach of people who drink alcohol. As ideas for textbook writers, here are some specific examples: the elongated, legless body of snakes is, according to Lamarck, a consequence of their «habit of crawling on the ground» and their «passing through narrow spaces»; the large size of herbivores such as elephants and rhinoceroses is due to their «continually consuming large quantities of food material» and of «making only moderate movements», so that their body «has greatly thickened, become heavy and massive». These same animals, because of their clumsiness, «are reduced to butting each other with the crowns of their heads», which explains the origin of horns and other similar structures, since this «causes an additional flow of fluids to that region, with a deposit of horny matter: hence the development of horns and antlers». For its part, «the bird of the water-side which does not like swimming (…) is continually liable to sink in the mud», so «it makes many efforts to extend and lengthen its feet, having gradually obtained long bare legs». Moreover, this same bird «wants to fish without wetting its body, and is thus obliged to make continual efforts to lengthen its neck», which «must have resulted in course of time in a remarkable lengthening». Like giraffes, but for a different reason.

However, Lamarck himself warns at the beginning of his work that «to avoid any error of imagination let us everywhere consult nature’s own works». Years later it was Charles Darwin, standing on the shoulders of giants like our imaginative gentleman, who made the most astute inquiries.