Each domain of knowledge has its own language, content and method. They give it character, and whenever a field of knowledge advances, it is thanks to one of them. Language is very important for science, but is not necessarily a priority. Old language can lead to new science. That is not a problem, no one is offended by that. Einstein’s special relativity theory was revolutionary when it was published in 1905, but those equations had already been used by Lorenz for his famous transformations, and his language was the same Maxwell used for the fundamental laws of electromagnetism. However, superstring theory is now debating the use of new mathematics, because the current one is not enough. Unlike in art. Content always orbits topics related to the human condition. No one is offended when modern works of art come back again and again to the beauty of a sunset, to passionate love, to an existential void, or to death. Nevertheless, in artistic creation, language takes charge. Art is classified and sub-classified through language: painting, sculpture, poetry, music… And in painting, for instance, we still talk about languages when we mention cubism, surrealism, impressionism or dadaism. Science lights an intellectual enjoyment that does not reach the mind directly through the senses. Conversely, the emotion of art does: painting uses sight, music uses hearing, sculpture uses what we could name visual touch… Each sense favour a different abstraction. Music, for example, is already an abstract art as it is. Perhaps that is the reason why realist music sometimes seems trivial or superfluous. But there are degrees: Beethoven’s Sixth Symphony or Vivaldi’s Four seasons evoke nature, but the abstraction is significant nonetheless, much larger than the scare suggested by the music of a horror film (watch one in silence to check this). There is sublime music that directly evokes reality, such as Pictures at an Exhibition by Modest Musorgsky, but it is the abstract component that turns music into art. Oddly enough, painting is the opposite case. Painting is itself a realistic language, so an excess of abstraction is trivial in this case. How can one reach the truth about the human condition through the paintings of Wassily Kandinsky or Jackson Pollock? Is it not a decorative discipline?

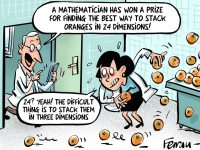

In science, we have a similar discussion regarding pure mathematics; that is, mathematics as a mental construction that does not depend on reality. Mathematics can be inspired by reality and successfully applied to reality, but owns nothing to it, because nothing in reality can refute, correct or discredit a mathematical structure or theorem. A scientist can make mistakes, exaggerate or lie when he reports an experiment. So there are frauds in science, but they are rare. However, no one commits professional suicide by publishing false, incoherent or misleading mathematics. Mathematics can be confirmed or refuted with pen and paper. So there is something in mathematics that is neither science nor art. Absolute and eternal truth exists, but only in mathematics. A mathematician is the only intellectual who deals every day with absolutes, with the eternal and infinite. The mathematical truth is clean, perfect, coherent, autonomous, necessary, beautiful, round and, above all, universal. No one has the privilege of mathematical authority, representation of profit. That is why mathematics may be the domain of knowledge where creators do not negotiate with anyone attempting to handle their truth. Perhaps they are the only ones who, annoyed, reject awards, positions, honours and privileges for love to that absolute and beautiful truth. This is the case with mathematicians such as Srinivasa Ramanujan, Alexander Grothendieck or Grigori Perelman, and with the first rationalist thinkers like René Descartes or Baruch Spinoza.