Back to nature

Landscape in the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and the Arts and Crafts movement

By the mid-19th century, the United Kingdom had reached the peak of industrialisation and economic expansion, while also revealing the first drawbacks of progress: social inequality, urban overcrowding, and aesthetic discontent as a result of production techniques. In this context, and in opposition to the prevailing academic art, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was born. In paintings prior to Raphael and medieval legends, they sought the authenticity they considered had been lost in their time, directing their attentive gaze towards nature. From the outset, the Brotherhood had the support of the art critic John Ruskin. Indeed, his writings on a new economic ethics and the creative and dignifying value of craftsmanship marked his «disciple» William Morris and the Arts and Crafts movement.

Keywords: John Ruskin, Pre-Raphaelites, Arts and Crafts, landscape, decorative arts.

The beauty/nature pairing is multifaceted and inviting. It can evoke a multitude of images: the Parthenon in Athens; Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater in Fayette County (USA); Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man; the Delphos gown by Mariano Fortuny; Jill Sherman’s Instagram account Fashion Biologique; the lion hunt from the palace of Nineveh; George Stubbs’ swift thoroughbred Whistlejacket; the metamorphosis of butterflies by Maria Sibylla Merian (Schmidt-Loske, 2009); the landscapes by Santiago Rusiñol or Joaquim Sunyer (López Blázquez, 1996); Ralph Vaughan Williams’ Sinfonia antartica; Dmitri Shostakovich’s Song of the forests; Antonio Machado’s Fields of Castile; Miguel de Unamuno’s poem «To Gredos»; Émile Gallé’s glass vases covered in dragonflies and lilies; the arabesques decorating the Medina Azahara; Eero Saarinen’s organic furniture; or designs based on biomimetics such as the Eastgate Centre in Harare, the capital of Zimbabwe, which is passively cooled through tunnels and is modelled on the natural ventilation of termite mounds in the desert. Of all these manifestations of nature-inspired beauty, and thousands of others we could choose from, I will focus this article on the landscapes of Pre-Raphaelite artists and the designs created by the Arts and Crafts movement. However, I would like to insist that what follows is only a small sample from among many possible ways of dealing with this issue.

«The three of them knew»

«The three of them knew». Thus begins Jorge Luis Borges’s «Ein traum» (‘A dream’) (Borges, 1978), and so did the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in London in 1848. Its three founders – William Holman Hunt (1827–1910), John Everett Millais (1820–1896), and Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882) – «knew» that only through a respectful and profound study of nature, «rejecting nothing, selecting nothing, belittling nothing» (Ruskin, 1883), would they achieve beauty and renew the dominant academic art of 19th-century England. These three young rebels, aged between 19 and 23 and enrolled at the Royal Academy of Arts in London, set a new style based on the direct observation of nature. On their excursions into the countryside, the three of them carrying their easels on their backs and painting the landscape au plein air just as it appeared before their eyes, they revolutionised 19th-century Victorian painting. The Brotherhood sought the simplicity and truth that they considered had been lost since Raphael – hence their group’s name – through an art of light, vivid colours, and poetry (Fahr-Becker, 1996). Their principles intertwined the beauty of nature with the seduction of simplicity, while aspiring to recover values that had long since disappeared.

John Ruskin and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

By then, the three young men were already familiar with the example of the Nazarenes, a group of German Romantic painters including Johann Friedrich Overbeck and Peter von Cornelius that, from 1810 onwards, turned their gaze to 14th- and 15th-century Italian art to connect with nature and artisanal tools in order to revive the Christian art of the Middle Ages (Gibson, 2006). But it was the art critic and social reformer John Ruskin (1819–1900) who really inspired and gave credibility to the Pre-Raphaelite movement. In his work Modern painters (1843), he assigned the art of the early Italian and Flemish artists at the highest level of excellence because of its authenticity. In his writings, Ruskin defended the idealistic aim of the Brotherhood: the study of nature to recover the aesthetic innocence of the art of those centuries.

Thus, Pre-Raphaelite art came to flourish through its depiction of landscapes and female portraits in themes inspired by mythology and ancient and medieval literature (Birchall, 2018). Their style would be characterised by extraordinary precision and, according to their aesthetic postulates, their works should always be absolutely beautiful and plausible.

Scientific observation of the landscape

The Pre-Raphaelites, before the Impressionists, set up their easels in the open air, through wind, cold, or rain, because the most important thing for them was to observe nature with almost photographic precision. This was possible thanks to the invaluable help of the newly invented tin roll-up paint tubes (1841). Previously, oil paint could only be kept fresh inside a pig’s bladder and was very difficult to transport once opened. With the attention of a scientific illustrator, the Pre-Raphaelites recorded what they observed with realism and accuracy: they transferred every little detail to the canvas, with absolute fidelity to the model, and left aside anything that was deemed anecdotal, exotic, or picturesque. In some cases, they used magnifying lenses to appreciate the smallest variations in shape and colour. Reproducing nature faithfully became an obsession for the Brotherhood. Their work was characterised by filling every inch of the canvas with the same intensity and paying the same attention to every element, both the main and secondary ones. The Pre-Raphaelites spent hours, days, and even weeks to finish a part of the work. Everything was considered important, and everything had to be painted just as it looked, without idealising or adding anything, because nature, they argued, is beautiful in itself, just as it is. There was no need for artifice. Many of their creations are pure landscapes, with nature as the only subject; in others, the landscape is a stage upon which the story unfolds. For works in this second category, the artists worked in two phases: they painted the landscape outdoors – to soak up the light and the nuance of natural forms – and then added the figures in their studio.

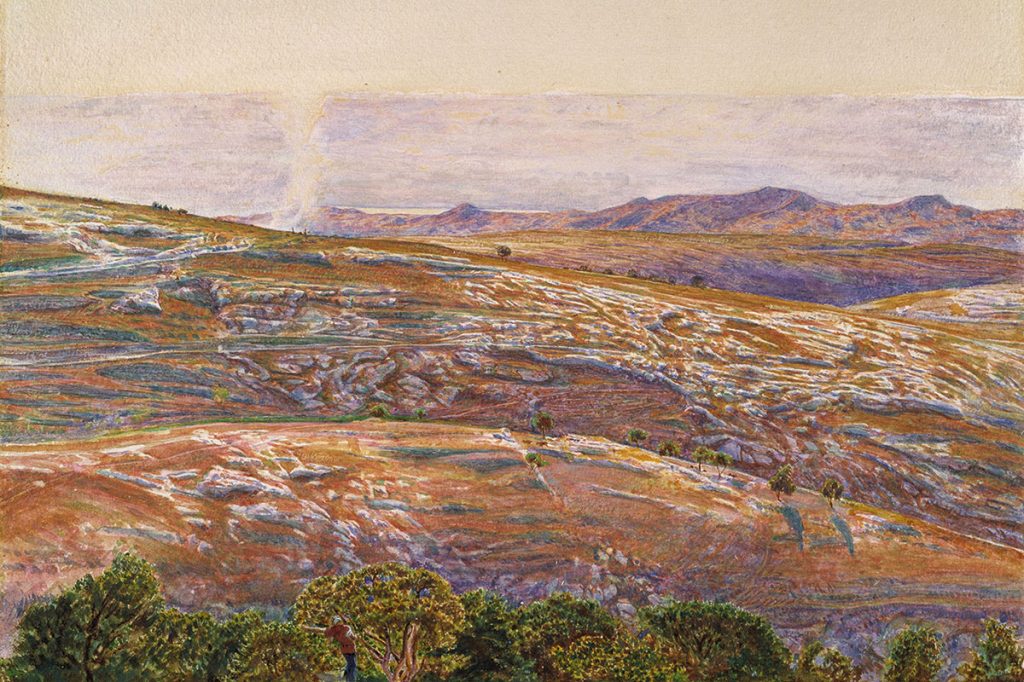

Figure 1. William Holman Hunt. The Dead Sea from Siloam (1854–1861). Watercolour, 34.8 × 24.8 cm. William Holman Hunt, striving to be faithful in his depiction of nature, created a new way of approaching the incidence of light on the landscape based on the use of light shades on a white background. The work was produced in the Holy Land and depicts a view from the Mount of Offence – the southern and lowest peak of the Mount of Olives – in the south-east of Jerusalem, looking towards the Dead Sea and the mountains of Moab. / Birmingham Museums. Public domain

William Holman Hunt and William Dyce

William Holman Hunt was the first to see landscape as a means to break with academic art and approach the essence. He was the only member of the Brotherhood who, over time, remained true to the original principles. Holman Hunt painted everything: the coast, countryside, forests, rock formations, animals, and skies of England, but he also left precious views of the white light present in Egypt and the Holy Land, where he had travelled on several occasions with his companion Thomas Seddon (1821–1856), another Pre-Raphaelite landscape painter. In The Dead Sea from Siloam (1854–1861) (Figure 1), Holman Hunt’s deep spirituality is reflected in the detailed incidence of light on the gentle hills of the Moab. Over time, Holman Hunt took a new approach to landscape without forgetting the beauty of the lines and form of his masters. His process was based on the use of light shades on a white background, in a commitment to be faithful to the representation of nature. His preference for drawing and his self-demanding character would lead him to work on multiple sketches of the same subject, to which he returned again and again until the work was completed. One example of this is his breath-taking view from the Mount of Offence overlooking the Dead Sea and mountains of Moab, a piece he worked on for seven years until he considered it finished. To paint it, he got up before sunrise, day after day, and on trip after trip, each made at the same time of the year to try to capture the same exact light every time. Looking for the same light, the painter and sculptor Antonio López commented in his latest interview in El Cultural: «Some things do not depend on me, the models, the sun, the moon… It is only up to me to get up every day at the same time…» (Espino, 2022). Holman Hunt’s watercolours are an example of why the Pre-Raphaelites are recognised as pioneers in the observation of contrasts of light and colour in nature. This observation was copied two decades later by the French Impressionist painters.

Figure 2. William Dyce. Culver Cliff, Isle of Wight, 1847. Watercolour, 26.2 × 17 cm. William Dyce reproduced the physical reality of the English coast in detail. The artist used men picking up the remains of a ship’s hull and some fishermen on the shore to depict the length of Sandown Bay, with the eroded white chalk cliffs of Culver Down clearly visible in the distance. / The Met. Public domain

When portraying nature, nothing was left to memory; all the elements had to be present in situ and reproduced in scientific detail: a bramble, insect, or crests of the waves. «Microscopic» observation of the natural environment was a requirement. Every detail mattered and had to be translated accurately onto the canvas. These artists meticulously reproduced everything that was presented before them. Thus, while working on a royal commission for Osborne Castle on the Isle of Wight, William Dyce (1806–1864) – whose style was very close to that of William Holman Hunt – painted, for his own pleasure, Culver Cliff, Isle of Wight (1847) (Figure 2), a watercolour in which he copied the eroded surface of the white chalk cliffs of Culver Down with the rigour of a geologist. If he introduced figures on the canvas, it is only to bring the viewer’s gaze even closer, if possible, to the magnitude of Sandown Bay.

Figure 3. John Everett Millais. The blind girl, 1856. Oil on canvas, 62 × 83 cm. Two girls rest under a cloudless sky; it has just rained. The smaller one admires the landscape and the double rainbow, while the older one, deprived of sight, cannot enjoy the natural beauty around them, including the small tortoiseshell butterfly resting on her cape. The scientific precision pursued by the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood can be seen in how accurately the order of the colours in the double rainbow are represented. When this phenomenon occurs, the arrangement of the colours is reversed in the outer arc, and this is how Millais depicted it. / Birmingham Museums. Public domain

John Everett Millais, Evelyn de Morgan, and John Brett

In Ophelia (1852), John Everett Millais painted the willow, nettles, and daisies, as well as the necklace of violets worn by Hamlet’s lover, all with the exhaustiveness of a botanist. Moreover, the scientific precision that preoccupied Millais and the other painters of the Brotherhood can be seen in the order of the colours in the double rainbow in his work The blind girl (1856) (Figure 3). Once the painting was finished, the artist was warned that, in double rainbows, the outer arc reverses the order of the colours. Millais had originally painted the colours in an identical arrangement in both rainbows, but quickly altered the order of the second to achieve the desired accuracy in copying nature.

In the same line of determination and finesse, but 40 years later, Evelyn de Morgan (1855–1919) – who, at the beginning of her career posited herself as a Pre-Raphaelite – depicted the Roman goddess of nature in front of a fruit-laden loquat tree with two goldfinches and a chaffinch perched on its branches in her painting, Flora (1894) (Figure 4), which was clearly reminiscent of Sandro Botticelli’s Allegory of Spring. The level of detail in the flowers, birds, and clothing is of a naturalistic precision and beauty reminiscent of the Italian Quattrocento, the movement that inspired the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (De Osma, 2015).

When John Brett (1831–1902), one of the most landscape-centred Pre-Raphaelites, painted Kynance (1888) (Figure 5), he not only expressed his adherence to Ruskin’s principles of beauty and the sublimation of nature, but also his interest in and knowledge of geology (Morel, 2015). This work depicts The Bishop rock at Kynance Cove, one of the most beautiful natural sites on the Cornish coast, known for its impressive rock formations. The purplish rust of the rocks in the foreground contrasts with the pale, autumnal grass in the background and the bright colours of the foamy waves at the foot of the painting.

At first, the scientific observation of nature promoted by the Pre-Raphaelites attracted numerous imitators, but enthusiasm soon waned because of the laborious technique that this type of research required. Even Millais, one of the founders of the Brotherhood, was already painting more freely and with less stylistic precision only four years after the group’s foundation – with notable exceptions such as The blind girl. His justification was that to support his large family, he could not invest so many hours in completing every small section of each canvas. Rossetti also moved away from the Pre-Raphaelite ideal of faithfully depicting nature, but for different reasons: he became more interested in the typical themes of medieval poetry. However, both Millais and Rossetti continued to fill their works with beauty and seduction.

Why the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood?

Figure 4. Evelyn de Morgan. Flora, 1894. Oil on canvas, 88 × 199 cm. In this painting, inspired by Sandro Botticelli’s Allegory of spring, we see a fruit-laden loquat tree with two goldfinches and a chaffinch perched on its branches, as well as the roses and camellias that Flora holds in her hand alongside the various flowers at her feet. Every detail is of such remarkable naturalistic precision and beauty that they remind us of the Italian Quattrocento, the movement that inspired the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. / De Morgan Foundation. Public domain

In the difficult definition of the concept of beauty, we find patterns that are repeated in nature: proportion, regularity, harmony, repetition, and symmetry. Think, for example, of the radial symmetry of the arms of a starfish or the lateral symmetry of a butterfly. Think also of how the meanders of a river curve again and again, or of the collection of pockets of gas that form foam. When these patterns occur in objects, they are often perceived as beautiful. The Pythagorean school spoke of mathematical beauty, and symmetry was one of its qualities. Classical Greek architecture is also based on these principles, on balance and the harmony of proportions, on order and geometry. Furthermore, although nature is not always literally symmetrical and its forms are not always geometric, it does have regular, repetitive, and ordered patterns whose contemplation is a source of inspiration for creating beauty. As the Roman poet Juvenal said: «Never does nature say one thing and wisdom another».

From the Greece of Pericles to the present day, with greater or lesser intensity depending on the period, artists have looked to the proportions and rules of nature and tried to achieve beauty in their creations. For the Brotherhood, beauty consisted in capturing natural reality, by which they meant everything that exists and is determined by its own laws, excluding human-made artificial objects.

John Ruskin and the Brotherhood emerged in the Europe of steam engines and industrialisation, at the zenith of mass migration from the countryside to cities (or to colonies). Their postulates were born at a time when, for the first time in human history, humankind was turning its back on nature and separating itself physically from the rural environment. The 1841 census revealed that, in the north of England, there were already more people living in towns than in the countryside. Factories changed and spoiled the skylines of the cities. The abrupt metamorphosis of everyday life and that new relationship with urban order – organised according to economic criteria, turning its back on nature and traditional values – were the trigger for Ruskin’s and the Pre-Raphaelites’ vindication. But Ruskin went further by looking back to Gothic architecture, the beauty of medieval buildings, and the craftsmanship of the artisans who created them, as opposed to modern mechanised production, which denied individual creative freedom and dehumanised their work.

William Morris and the Red House

In the second third of the 19th century and with the second generation of Pre-Raphaelites, including the emblematic painter Edward Burne-Jones (1833–1898) and the architect and designer William Morris (1834–1896), the aesthetic concerns learned from Ruskin reached the world of decorative arts. Burne-Jones and Morris were close friends and collaborators throughout their lives, both vindicating the value of applied arts through their work.

In 1859, Morris commissioned his partner, architect Philip Speakman Webb (1831–1915), to build a house in Bexleyheath, south-east London, for his wife Jane Burden (1839–1914) whom he had married that same year. Burden, a young woman of humble origins, embodied the ideal of Pre-Raphaelite beauty: tall, slender, with long dark curly hair, large eyes, and a natural elegance. At the age of 18 she became the muse not only for Morris, but especially for Rossetti, who chose her as the model for many of his works, such as Proserpine (1874) and Astarte Syriaca (1877).

But let us go back to the Red House, so called because of the colour of its brick walls. The house – simple, functional, and integrated into the landscape, and described by Burne-Jones as the most beautiful place on Earth – was entirely decorated by Morris, Webb, Burne-Jones, and other Pre-Raphaelites because Morris and Burden had found it difficult to find manufactured goods to fit their taste. This was the Brotherhood’s first global work of art. The architecture, furnishings, wall paintings, tapestries, and stained-glass windows in the Red House all reflected a deep respect for artisanal work. Morris’s home can be seen as a paradigm of this doctrine: art and beauty born from craftsmanship.

The Red House experience encouraged this group of friends united by a common ideology – to regenerate craftsmanship by creating simple, useful and beautiful pieces – to set up their own decoration company. The Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. firm, also known as The Firm, started to produce and sell wallpapers, furniture, printed fabrics and embroideries, tapestries, ceramics, tiles, and stained glass in 1861, and was later renamed Morris & Co. when Morris became its sole owner in 1875. Morris & Co. specialised in wallpaper prints and textile works (figures 6 and 7). The tapestries, based on Burne-Jones’s sketches, are considered the most beautiful of the period.

Figure 5. John Brett. Kynance, 1888. Oil on canvas, 35.9 × 17.8 cm. John Brett, known for his geological knowledge and his meticulous depictions of the natural world, embodied John Ruskin’s creed in his works: to be true to nature. This work depicts the Bishop rock at Kynance Cove, one of the most beautiful natural sites on the Cornish coast, known for its impressive rock formations. The purplish rust of the rocks in the foreground contrasts with the pale, autumnal grass in the background and the bright colours of the foamy waves at the foot of the painting. / The Met. Public domain

Morris focused on nature and craftsmanship and was probably the one who did the most for art education in his country. He adopted and developed Ruskin’s and the Brotherhood’s main aim: he made everyday objects beautiful by incorporating plant and animal elements in rhythmic, organic forms taken from nature into decoration, together with motifs from medieval ornamentation.

The Arts and Crafts movement

It was in this context – with paint coming out of the canvas and into everyday life – that the Arts and Crafts movement arose. The name was first used in 1887. The movement brought together architects, designers, and craftsmen who shared Morris’s ideas and concerns regarding the negative impact of industrialisation on working conditions and traditional crafts, and his thoughts on the ugliness of objects born of mechanisation. The members of the Arts and Crafts movement, who organised influential exhibitions between 1888 and 1916, revived obsolete crafts by studying the nature of materials and giving them new possibilities: wood, natural (non-synthetic) dyes, ceramics, blown glass, embroidery and tapestry, metal and leather embossing, plasterwork, enamelling, and bookbinding. Each object and element had to be designed as part of an organic whole: a total work of art (Figure 8). Unsurprisingly, for Morris, next to a beautiful house, the most important work of art was «a beautiful book» (Fontán del Junco & Zozaya, 2017). This was Morris’ last achievement – the founding of Kelmscott Press in 1891 – a printing house in which he designed typefaces, hundreds of covers, capital letters, frames, and other minor ornaments, always of natural and medieval inspiration. Together with his closest and dearest collaborator Burne-Jones, he edited carefully illustrated books (such as Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury tales) that were considered the peak of publishing craftsmanship.

Figure 6. Strawberry thief (1883) is perhaps one of William Morris’s most recognisable and successful textile designs. It is a tribute to the thrushes in the garden of his summer home Kelmscott Manor, in the south of England. In this piece, Morris began to experiment with natural dyes and revived the printing technique known as «indigo discharge», which consists of first dyeing the fabric completely blue and then bleaching particular areas to be printed in other colours using woodblocks. // Figure 7. William Morris designs (Pink and rose, Wilhelmina, Willow bough and Golden lily) for wallpapers produced between 1877 and 1890 and marketed by Morris & Co. The lilies, tulips, willow leaves, roses, carnations, acanthus, and honeysuckle leaves that inspired his abundant and orderly creations are still reproduced today in a variety of objects, such as this delicate tableware.

Although Arts and Crafts was an essentially urban movement, the longing for rural life and manual labour were its two main ideals. With this movement, nature went from being observed and replicated with scientific precision to becoming a source of inspiration, both for materials and for ornamental motifs, including flowers, leaves, twisted stems, fruits, peacocks, pigeons, and deer. The goal was to create that beautiful house and that beautiful book that Morris spoke of.

Figure 8. Philip Webb’s The backgammon players (1861), ornamented with a leather painting by Edward Burne-Jones, is a masterpiece of the Arts and Crafts movement and its attempt to avoid the evils of industrialisation. This cabinet is an example of a beautiful and functional piece of furniture combining fine and applied arts. Philip Webb’s simple design in the outer casing of the piece emphasises the structural elements that would start the revolution of design in the following century. / The Met. Public Domain

At the end of the 19th century, the time of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and the rigorous precepts of John Ruskin seemed a long way off, but we must recognise the considerable influence that the Brotherhood, born of the three non-conformist spirits of William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, exerted on the advent of modern English art and the Arts and Crafts movement. They imbued it with many of the movement’s characteristics, including the most poetic symbolism and an artistic current which emerged at the turn of the century, and which was given different names in different countries: Modernismo in Spain, Art Nouveau in France and Belgium, Jugendstil in Germany, Modern Style in Great Britain and the United States, or Sezession in Austria. Thus, these movements incorporated the beauty of nature into their creations with the same fervour the Pre-Raphaelite artists had.

References

Birchall, H. (2018). Prerrafaelitas. Taschen.

Borges, J. L. (1978). La moneda de hierro. EMECE.

De Osma, G. (2015). Fortuny. Nerea.

Espino, L. (2022, 14 March). La gran entrevista a Antonio López: «Otros se obsesionan con la muerte, yo por el dinero». El Cultural. https://www.elespanol.com/el-cultural/arte/20220314/gran-entrevista-antonio-lopez-obsesion-muerte-dinero/656434564_0.html

Fahr-Becker, G. (1996). El modernismo. Koneman.

Fontán del Junco, M., & Zozaya, M. (Coord.). (2017). William Morris y compañía: El movimiento Arts & Crafts en Gran Bretaña. Fundación Juan March.

Gibson, M. (2006). El simbolismo. Taschen.

López Blázquez, M. (1996). Joaquim Sunyer. Ediciones Polígrafa.

Morel, G. (2015). Les préraphaélites, de Rossetti à Burne-Jones. Éditions Place des Victoires.

Ruskin, J. (1883). Modern Painters, Volume 2. Orpington.

Schmidt-Loske, K. (2009). Maria Sibylla Merian: Insects of Surinam. Taschen.