Interview with Sydney Brenner

«The most important thing is motivation»

Promoter of the deciphering of the genetic code and Nobel Prize for Medicine in 2002.

Although he later became a naturalised British citizen, it was in his native South Africa (Germiston, 1927) that scientist Sydney Brenner, drawn by plants pigments, discovered his interest in the natural world and in experimentation. His growing curiosity and an amazing intellectual ability led him to be accepted in the public school two years early. He was only 15 years old when he enrolled in the Medicine Faculty, influenced by the fatherly dream of a humble family. The studies in anatomy and physiology brought him closer to cells and their functions. He was the pioneer of a yet non-existent science, molecular biology. The display of DNA structure in 1953 became a milestone in his career and an impulse towards the deciphering of the genetic code, his greatest breakthrough. He was awarded the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 2002, together with John Sulston and H. Robert Horvitz, because of their discoveries on genetic regulation of the development of organs and programmed cell death (apoptosis), a late reward as an exceptional figure in biology and genetics. Currently a scientific director in a laboratory in La Jolla and another one in Singapur, Brenner has received different prizes such as the Louis Jeantet de Medecine in Switzerland, and honours like the one awarded by the Max Planck Society or the one by the Academie des Sciences. Despite the titles, he prefers his work to speak for itself.

Motivation is probably Sydney Brenner’s elixir of youth. He is 77 years old and still keeps his enthusiasm towards scientific research and a lucid brain to advance a career full of new drive and devoid of obstacles, despite having already achieved the greatest scientific prizes. He is a rebel, non-conformist researcher whose highest aspiration was to understand the functioning of the most complex machine: our brain. From an early age, Brenner, a tireless reader, found in science communication and philosophy an endless source of knowledge, as well as the excitement to carry out the first experiments in his father’s shoe repair shop.

«When I formulate a hypothesis, I never think I’m describing unreal or impossible things, I wait for nature to confirm it»

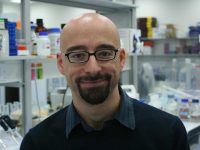

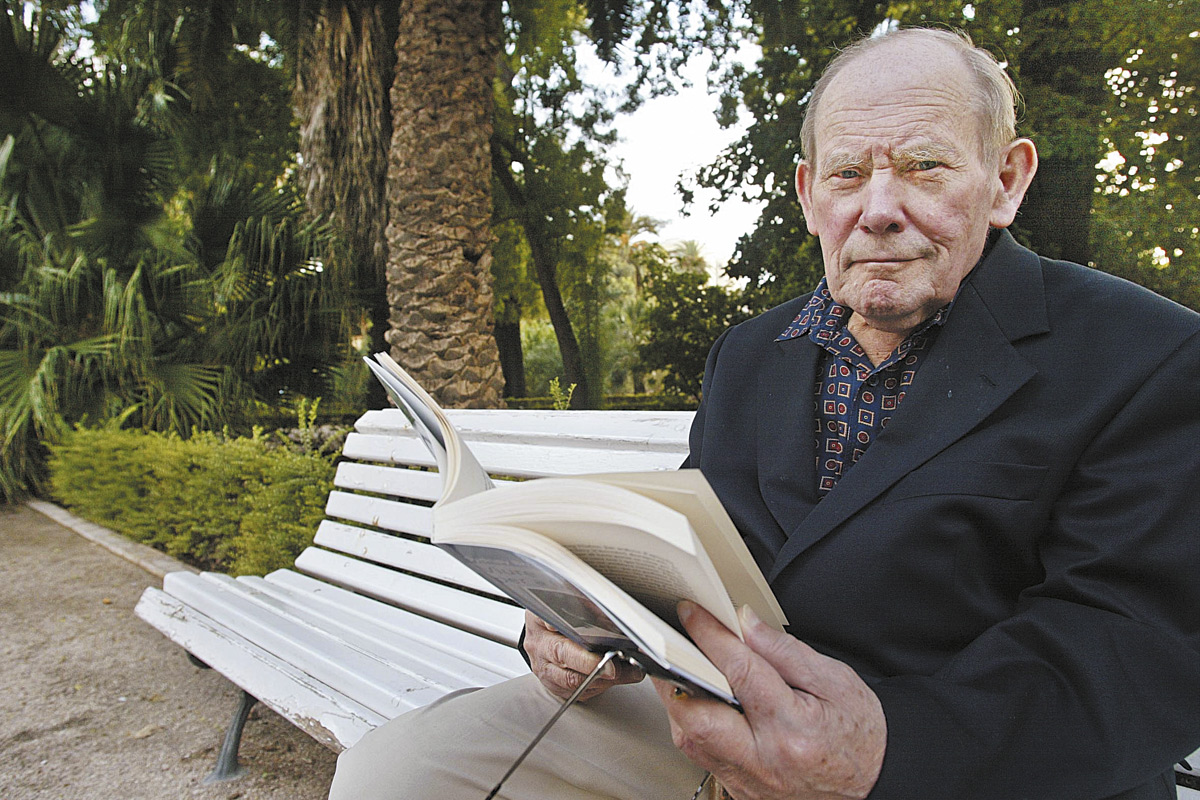

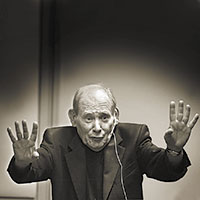

Brenner keeps his restless spirit and wit perfectly. He became one of the most outstanding people in the second half of the twentieth century with his discoveries about the genetic code. His eyes, enervating and bright blue, transmit the curiosity with which he observes what lies around him, and his thick and stiff eyebrows raise as he speaks and when he suddenly whispers a sour joke. His words are a mystery for the interviewer, and his next spurt of critical humour.

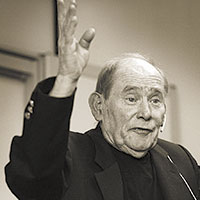

He is a passionate talker, he likes spending is not easy to guess nights entwined in conversation, circling new ideas, questioning and answering himself, clumsily gesticulating with his large arms. In fact, he considers his autobiography «My Life in Science» a «biophony», a transcription of his long conversations with embryologist Lewis Wolpert.

With his cane and without his characteristic tiny sunglasses, he waits for us in an armchair in the Astoria hotel, where he is lodged while he teaches a course in the UIMP about how to read genomic sequences and presents his autobiography invited by the Chair for Scientific Dissemination of the University of Valencia. He wears a black, loose shirt that goes down past the waist, earth-brown summer trousers and brown deck shoes. He receives us friendly yet without a handshake, inviting us to look for a more private place to avoid the bustle of the hotel reception.

Photo: M. Lorenzo

In your book, you define yourself as a self-educated person, who learned thanks to reading and experimenting. ¿What is the role of these two activities for the new generations?

I thinks reading and self-learning is a feature of my generation. I mean, learning alone and trying to experiment with what the books teach you. However, current North American students are lazier and they just follow a specialised academic course in a subject, or they have everything prepared in a computer. That is one of the consequences of the industrialisation of science! Everything is taken for granted.

But the true scientist needs to work in the lab. In Cambridge and Oxford people start working in the lab right away, while in the United States young students have to pass two or more quality courses before, during which professors just teach their lessons. Nonetheless, I always tell my students that they «need to start working in the lab». It’s easy to learn a new subject by yourself, even if people think you have to follow a course and study it.

In fact, I think the interest of young people in science disappears when teachers say «this is the syllabus, these are the questions». At first, many young kids are interested in the natural world, but by the time the finish school, they lose their inquisitiveness because they take everything for granted and they do not work in the lab.

Are scepticism, curiosity and motivation the keys to push scientific research forward?

The most important thing for me is motivation. If someone comes to the lab and has no curiosity for researching, trying and experimenting, I’m not interested in him. In my laboratory I had an Argentinian student who was not qualified for the subject, but was always asking for more things to do and paying attention to the lessons. Today he is an excellent scientist. However, we don’t simply give jobs to North American trash just because they studied the five years of the degree. The important thing is for them to be motivated, and I have a special instinct to detect the ones who are interested and want to improve.

«The greatest achievements will come from the field of brain structure. We currently have no idea how it works»

Is it maybe this interest for experimentation and problem solving that led you to formulate the «don’t worry hypothesis» (Brenner, 2011)?

The «don’t worry hypothesis» is an interesting thing, because it forces you to keep going without losing your mind over mechanisms. My classical example happened when, after observing DNA structure, I suddenly thought the two acid strands would unfold to copy the structure through enzymes. Many people said, though, that what I was claiming was absolutely wrong, because it was impossible for the strands to unfold.

Nevertheless, I said «don’t worry», let’s leave that issue apart for the moment, because the cell does it one way or another. And, in fact, DNA helicase was later found, as well as other proteins with the function of unfolding the double helix. When I formulate a hypothesis, I never think I’m describing unreal or impossible things, I wait for nature to confirm it.

You say: «I think outsiders who have not researched a specific method are the ones who can see things differently and take a new step forward». Is this the case with molecular biology?

On most occasions, being an outsider, as I was in biochemistry, enables you to work better, free from rules and the status quo. Actually, the biochemistry Establishment saw us, molecular biologists, as intruders; they said we were biochemists working «without a permit». I now realise that immigrant students, trained outside the American system, in places such as Singapore and Shanghai, experts in engineering and computer science, are really good because they have a lot of practice with machines and know how to take advantage of them in a field they do not know, biology. As a matter of fact, I bet they are the future generation that will work in this scientific field. They don’t have any pre-established opinions or ideas, and they are really fast learners. If I were twenty years youngers, I would have that attitude. Asking about things is the best attitude.

Photo: M. Lorenzo

What is the best incentive to work in science?

A man once tried to take me to his television programme, one with a huge audience, to explain why I did science, and I said, «let me tell you, it’s not for the money, it’s for the women!» [He laughs, obligingly]. «Are you serious?», he exclaimed, shocked. «Of course!» I said, «Who wouldn’t want an ambitious man who works for humanity?» I have to admit, in the end I was not in the programme.

Honestly, I like solving problems and science is a good way to do it. Expanding knowledge motivates me. Every one has different motives. Others want science to be successful, but I think the most interesting thing in life is to work in something you like. Around 95% of scientists are not allured by science, they just want their salary, which they use during the weekend in whatever they really like.

What did the Nobel Prize mean for your professional career and your personal life?

Nothing! No changes. That is true, I’m honest. One of my complaints is that you have to do a lot of interviews when you win a Nobel, it is a waste of time! [We laugh together]. In addition, you know the awards are given on the day that Alfred Nobel died, around November. In this sense, I think the doctors should have planned his death for six months before or after, because it is too cold in Stockholm in November! In a nutshell, the Nobel didn’t even deserve my opening a bottle of 1964 Vega Sicilia!

Your book reflects your interest in philosophy from an early age. What is the role of philosophy in science?

I think one of the best things that happened to me when I studied in South Africa was the History of Science Philosophy course I attended to. I had a good teacher who transferred her interest on the development of the scientific method and knowledge structure to me. Everything from medicine to sociology must be integrated on it. The most important thing is to put together all the points of view and creating an integrated knowledge, as well as studying humanities. I think all the politicians would have to attend this course and know these ideas, even if it was only during the first semester.

Actually, with the progressive evolution of technologies, I think the big problem to deal with in the future will be the loss of knowledge philosophy. Philosophy is like wine [Brenner is a big lover of the wine culture], it should not be consumed quickly, you need to taste it slowly.

Philosophy helps scientists to be conscious and to think about what they are doing. Because of that, it should enjoy more attention in biology studies, and in science in general.

Many scientists are still active at an age that other professionals decide to retire. What is the secret to keep yourself young and active at the age of 75? Is research the elixir of youth?

No, I think it is the urge to survive! The most important thing is to keep going, to keep thinking of new things to do, not to waste any time. True, I’m not as young as I was, but as long as my brain is clear and useful, thing will work out fine.

Photo: M. Lorenzo

Mètode’s issue 44 contains a monograph on the concept of ageing. Some authors consider ageing as part of the development process of an organism. Do you agree with this opinion?

Well… it is not exactly like that. In fact, I think the whole idea of the development process of an organism and ageing is a fraud. In reality, if we use scientific terms, the idea should become a myth because evolution worked quite hard to survive and develop and, as we can observe, generations are increasingly young. Over time, there will be such specific technologies that they will even prolong life and erase the idea of generation.

Besides, the USA wants to push us towards immortality, to live equally and forever, like gods. There is an opera called «The Makropulos Affair» by Leoš Janáček, in which the leading character is an opera singer who lived more than 300 years thanks to an elixir that gave her extraordinary longevity. In a point of the opera, another character asks: «What is the meaning of life if you can never die?» It is an interesting philosophy. Death is the energy pushing you to live.

Valencia is one of the Spanish cities where mother cell research has advanced the most. However, research finds obstacles to keep going, because of the Catholic Church and some conservative political lines. What is your opinion on therapeutic cloning?

Ethics has always justified that some people are victims and only one holds the power: God. But I ask myself, where is that psychopath we call God? I’ve never seen him. And if there is a God, it is one we cannot trust, because if he’s meant to protect us, how can he let millions of people die every day? Is there not enough God for everyone? Maybe he needs more staff.

Anyway, I don’t see the problem with therapeutic cloning. There is no reason not to do it, because if we establish that we can theoretically create clones, there will someone who goes further and creates real clones. Actually, everything grows thanks to change, and change pushes things forward. You can’t go back from a moment of change. The chicken won’t turn into an egg again. These are natural changes, so cloning doesn’t need to have a civic aspect. Animals practice this cloning, look at salamanders, who used mother cells much before we happened to think about cloning.

«The whole idea of the development process of an organism and ageing is a fraud»

What are the difficulties today for genetics research?

Blabbermouths, people who talk too much and do too little. I think genetic research today finds lots of opportunities and has spectacular state-of-the-art technology. New signification opens for the field, because now, apart from the strength of science they have the support of technology.

Which biology area do you think will see the most spectacular breakthroughs in the twenty-first century?

In this century? It is too soon to say! We have only walked 5% of the way! It is clear, though, that the greatest achievements will come from the field of brain structure. We currently have no idea how it works. This has been, and still is, the main issue. A lot of young people talk about these studies as the most interesting point in today’s research, that is, to be able to understand how the brain is built and how it works.

But what do you mean with the most spectacular? For me that means to be able to build, helped by genetic engineering, the centaur that the Greeks imagined, a hybrid animal with thoracic duplication and with the strength of two pairs of upper extremities. However, I wonder why the Greeks did not design any female centaur, and focused only on men. It is a fantasy speculation, but it gives us a deeper approach to possible genetic breakthroughs. However, the problem in this century is that new sorts of institutions force us to understand things differently. They have access to genetic manipulation, and the money to carry it out, and they actually respond to the desires of a new age.

Photo: M. Lorenzo

Such is Brenner’s taste for conversation that were it not for because of the presence of my notebook and the boredom he shows for interviews and media coverage of science, he would continue discussing without limit. The double significance of his answers and the sharpness of his wit reveal a scientist full of great ideas to express. His profound motivation and instinct have opened a new chapter in the interesting life of this practical and experimental scientist, who directs with his gaze on the future the Lynx company, a company that offers genetic analyses of products and innovation for the pharmaceutical, agricultural and biotechnological industries. His life is, possibly, devoted to a never-ending quest for knowledge.

Brenner, S, 2001. My Life in Science. The Science Archive Ltd. Gran Bretanya. [Versió catalana de Juli Peretó, Alzira, Bromera.]