«Detailed evidence shows that Nietzsche passed through each of the three stages: the chancre of primary syphilis; the terrible pox, fever and pain of secondary syphilis; and the dreaded third, paresis»

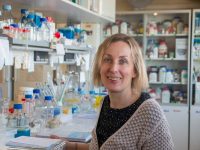

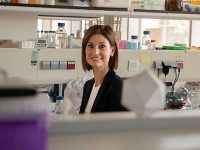

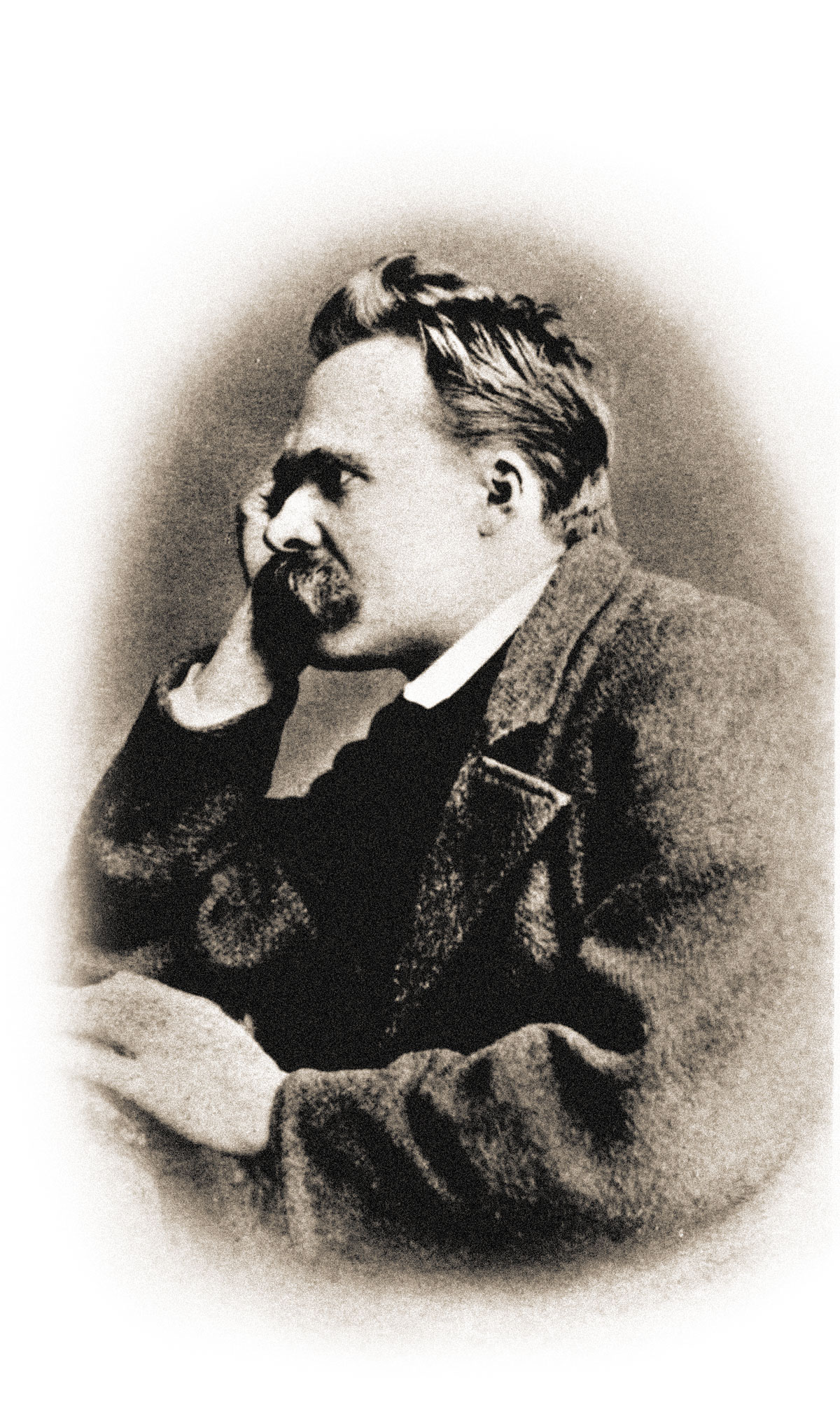

In the foothills of the Italian Alps, on a snow-draped piazza in Turin, on January 3, 1889, a driver was flogging his horse when a man flung his arms around the poor beast’s neck, his tears soaking its mane. The horse’s savior was the German philosopher Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (Prussia, 1844). His landlord later found him collapsed in the Squire and brought him back to his room, where Nietzsche spent the night writing a flurry of bizarre postcards. As soon as his friend and colleague Jacob Burckhardt received one of these crazed letters, he convinced his close friend Peter Gast to go and accompany Nietzsche on his return to Basel. Much of the rest of the century, the last eleven years of his life, Nietzsche spent in an incoherent madness, crouching in corners and drinking his urine. The most productive year of his life had been immediately prior to the psychotic break. After it, he wrote no more philosophy. Deborah Hayden, in her book Pox: Genius, Madness, and the Mysteries of Syphilis, summed up the famous incident:

The story of Nietzsche’s sudden plummet from the most advanced thought of his time to raving dementia is often told as if there were a razor’s edge demarcation between sanity and tertiary syphilis, as if on 3 January armies of spirochetes woke suddenly from decades of slumber and attacked the brain, instead of the biological reality that paresis is a gradual process presaged over many years.

Hayden’s case to prove that Nietzsche indeed suffered all his adult life from syphilis is as strong as any posthumous medical history can be. He was diagnosed at a time when clinical familiarity with the disease abounded. Detailed evidence shows that he passed through each of the three stages: the chancre of primary syphilis immediately after infection; the terrible pox, fever and pain of secondary syphilis that emerges from months to years later; and the dreaded third, paresis. Paresis, like the word syphilis itself, refers to a syndrome. An acronym, it expands to Personality disturbances, Affect abnormalities, Reflex hyperactivity, Eye abnormalities, Sensorium changes, Intellectual impairment and Slurred speech. Paresis often begins with a dramatic delusional episode, but in the following months and years, dementia alternates with periods of such clarity that there seems to have been a cure.

In the mid-twentieth century, after the introduction of penicillin in the United States, there was a general belief that syphilis could be easily eradicated. The efficacy of penicillin for early treatment, improved hygiene, condom use, and attitudes that lead the afflicted to seek help for venereal infection conspire to bolster the common myth that syphilis has disappeared. We are deceived; the spirochetes¹ that cause it are still among us and many people suffer from syphilis called by other names.

Sickness, inspiration and creativity

Nietzsche’s letters from 1867 until his breakdown in 1889 provide a vivid account of the suffering of secondary syphilis. He complains of the pain, skin sores, weakness and loss of vision that typify the repertoire of the disease. In his last years, his letters give evidence of euphoria. His published works show the grandeur and inspiration that tertiary syphilis sometimes brings to brilliant and disciplined creative minds by removing inhibition as brain tissue is destroyed. In Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1884) Nietzsche wrote, «The Earth, he says, has a skin, and this skin has a sickness. One of these sicknesses is called “man.”» What terrible insight Nietzsche must have had into the devastating horror of pox!

Multiple sources indicate that he was treated for syphilis in 1867 at the age of twenty-three. Seeking medical treatment for eye inflammation, a frequent syphilitic symptom, he consulted Dr. Otto Eiser, who reported not only on Nietzsche’s penile lesions but that he had engaged in sexual relations several times on doctor’s orders! Years later, in 1889, when Nietzsche broke down and was taken to the clinic of a paresis expert, he was admitted with the diagnosis: «1866. Syphilit. Infect.»

«His published works show the grandeur and inspiration that tertiary syphilis sometimes brings to brilliant and disciplined creative minds»

In 1888 Nietzsche’s productivity was, by any standard, extraordinary. He completed his philosophical project: Twilight of the Idols, The Antichrist, Ecce Homo, and The Case of Wagner. The style of these works is apocalyptic, prophetic, incendiary, and megalomaniacal, leading many scholars to claim the excesses of these works was due to incipient paresis. Now, after more than a half millennium of the study of syphilis and more than a century after Nietzsche’s breakdown, our research suggests that the philosopher really did plummet abruptly into madness; armies of spirochetes did awaken suddenly from decades of slumber and literally began to eat his brain.

The origin of syphilis

Many claim syphilis was known in Europe prior to the return of Columbus, but as Hayden describes and I agree, it is more likely the insidious venereal infection was a new gift of the Americas to the people of Europe. Columbus and his crew returned to Spain with a novel set of symptoms that soon spread to Naples and France. From that first year, 1493, the disease was described in detail, beginning with the physician who treated Columbus and his men, Dr. Ruy Diaz de Isla. Diaz de Isla reported, «And since the Admiral Don Cristobal Colon had relations and congress with the inhabitants … and since it is contagious, it spread.» Eventually it affected the waterfront prostitutes of Barcelona. Diaz, in a work published in 1539, wrote that infected sailors were accepted both into the army that Charles of France brought to besiege Naples in 1495 and into the forces Ferdinand of Spain employed to defend Naples. Ferdinand’s army alone is estimated to have had five hundred prostitutes among its camps followers. Soon after the victorious entry of Charles’s army, the Great Pox of Naples erupted. His multinational mercenaries brought infection back to every European country. By the next year, the disease spread across the continent, puzzling physicians with its novelty.

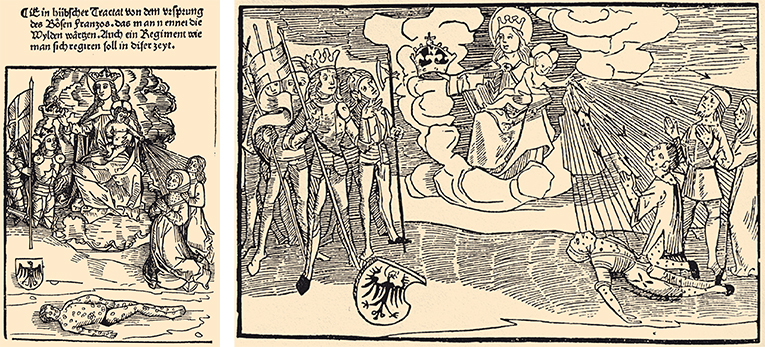

On the left, drawing from Joseh Grünpeck’s commentary on Brant’s pamphlet on syphilis (1496), on Sudhoff, Zehn Syphilis-Drucke. On the right, drawing from 1496, by Sebastian Brant, published in a pamphlet on syphilis, on Kark Sudhoff, Zehn Syphilis-Drucke aus den Jahren 1495-98 (Milan: Lier, 1924). The image shows a closed community of syphilitics, composed of three men and a woman, being punished with the flagellum Dei or Scourge of God, because of their sexual transgressions. The arrow represents the martyrdom of the sick, who suffer because of the fall of Adam and Eve. The figure of the baby Jesus indicates, however, the power of healing. In the image on the left, the figure of the sick man is instead presented in isolation. This emphasis creates the illusion that this man represents the exemplary patient, focused on his suffering and trying to reach the knowledge of the nature of the disease. This man is portrayed as the main victim of syphilis.

Poques dècades després dels primers contagis, entre un 5 i un 20 per cent de la població europea estava infectada de sífilis. La malaltia rebé diferents noms i un dels més difosos fou el de morbus gallicus, el mal francès, perquè les tropes de Carles de França eren considerades –potser encertadament– les causants de la introducció de la malaltia a Nàpols. Les obres dels metges que poc després del gran brot epidèmic de Nàpols escriviren sobre la malaltia en llatí, que era la lingua franca de l’època, tingueren una gran difusió. El 1530, Girolamo Fracastoro escriví un tractat en vers sobre la malaltia, que titulà Syphilis sive Morbus Gallicus, en què el protagonista, un pastor anomenat Syphilus, és el primer que pateix la malaltia com a càstig per la seva incredulitat. L’epònim aviat arrelà i el nom de sífilis és el que ha perdurat.

«Syphilis came to be called the French malady. Charles’s army was blamed for its introduction to Naples»

Within the first few decades of the contagion, in cities across Europe physicians reported that between 5 and 20 percent of the population suffered. Variously named at first, it came to be called morbus gallicus, the French malady. Charles’s army was blamed for its introduction to Naples – perhaps rightly. Physicians, who published in the lingua franca of Latin, soon after the disease’s great outbreak in 1495, drew international attention. Girolamo Fracastoro, in 1530, wrote a verse treatise on the disease entitled Syphilus sive Morbus Gallicus in which the eponymous protagonist, a shepherd, is the first to bear the disease, as a punishment for impiety. The name stuck.

Syphilis has been surprisingly well documented since its outbreak in the closing years of the fifteenth century, as microbiologist and sociologist of science Ludwik Fleck (1896-1961) wrote in his masterpiece about the genesis and development of scientific facts. From the sixteenth century trough the end of the nineteenth century the prevalence and peculiarities of syphilis led to publications from scientific arcane to torrid novels. In 1905 Erich Hoffman (Germany, 1868) send a genital chancre specimen to German microscopist Fritz Schaudinn (Germany, 1871), who confirmed the etiology. He aptly called the lively, translucent, thin, corkscrew-shaped bacterium he observed «thin, pale thread»: Treponema pallidum. Treponema pallidum spirochetes were found in the brains of patients that manifested tertiary syphilis symptoms by Udo J. Wile (New York, 1882) in 1913.

Syphilis has gained attention again because of its disputed relationship to AIDS. Today, although physicians rarely record cases of tertiary syphilis, the earlier two stages of the disease seem on the rise. AIDS patients who had a record in their past of syphilis and who were apparently cured by antibiotics succumb again to syphilis. «Syphilis in patients affected with HIV is often more malignant with a greater disposition for neurological relapses following treatment,» the scientist, not a physician, Dr. Russell Johnson of the University of Minnesota medical school, a world expert on the Lyme disease spirochete, said to me in his usual cautious manner. Dr. Peter Duesberg (California, 1936), one of the discoverers of the machinations of the retroviruses, rejects exclusive focus on HIV as the cause of AIDS. In his excellent book Inventing the AIDS Virus, he questions a prevalent assumption that, as a contagious virus, HIV is even the main cause of the lesions, tumors, rashes, arthritis, pneumonia, and other severities that accompany immunosuppression. These symptoms, including the detection in tissue of both the HIV antibody and the virus itself, may, as in other opportunistic infections, be the consequence he suggests, not the sole cause of AIDS. Joan McKenna, a physiologist with a thermodynamic orientation, wrote:

Because spirochetes can be harbored in any tissue for decades and can move from latency to reproductive stages, their survival in any host and despite any known therapy is nearly certain … [We also] know that unknown factors will activate the microorganism [Treponema pallidum] from latency into an aggressive infection…

McKenn went on to remark the relationship between syphilis and AIDS, that «no symptoms show up in AIDS that have not historically shown up with syphilis and the history of these populations [where AIDS is rampant] includes a high incidence of syphilis.»

Clinical confusions, misdiagnoses, anomalous symptoms, conflated multiple infections, abound from 1495 in the early work of syphilology until now. Yet many studies confirm the variety and severity of symptoms attributable to the Treponema pallidum spirochete. The malady remains idiosyncratic in its course, with variability in the timing of the stages and, even now, the absence of any reliable test or single diagnostic. Still, the evidence suggests that the virulence and severity of the disease have diminished dramatically sin the initial violent pox outbreak. No anomaly here needs explanation; rather, this behavior is expected of pathogens in first exposure to naïve populations. Syphilis in Europe showed the same pattern that measles and smallpox did when first introduced to the Americas by Europeans. As early as the first few decades that followed the Pox of Naples, subsequent generations of Europeans were more resistant. Pathogenic microbes maximize not by rapid lethality but by conversion to chronic disease that lasts a lifetime and subtly affects behavior in the stricken animal.

Since the late nineteenth century the Wassermann blood test has often been touted as the best diagnostic test for syphilis. The fear of syphilis transmission was once so common that the Wassermann test was, and often still is, legally mandated in many places, required prior to marriage. However, as shown by Fleck and others, the Wassermann reagent does not measure the presence of Treponema pallidum. It indicates, and not even 100 percent of the time, the exposure of a patient to unspecified infectious bacteria. A Wassermann positive test shows that a person makes antibodies against certain blood-borne bacteria that may include the syphilis treponeme. Furthermore, the test in known syphilitics in advanced stages of the syndrome converts: it is negative.

On another front, to preclude contagious mother-to-infant transmission of syphilis during parturition, drops of silver nitrate, thought to suppress the syphilitic spirochete, were placed in the eyes of most new-borns. This practice occurs in some regions even now and even when blood tests for syphilis in the mother are negative. These irrational practices measure residual fear of the contagion of syphilis.

Arsphenamine, better known as Salvarsan, was said to improve the health of syphilitic patients in the twentieth century. Often it made people sicker. After 1943 came the miracle drug: the claim was that a single or few massive doses of penicillin cured the body permanently of the dreaded treponeme. After hefty antibiotic treatment in newly detected patients the insidious corkscrews disappeared. Though tiny, shiny round bodies, the apparent remains of «dead» spirochetes, might sometimes be found in tissue, the moving treponeme was declared gone. A researcher in Paris in the 1950s, J. Pillot, after whom the beautiful large spirochete Pillotina was named, «proved» that the round body remnants of the lively corkscrew were not dead. The confusion comes from the fact that – penicillin or not – during the long latent phases of the disease after the primary chancre, moving corkscrew treponemes are not seen in tissue in any case. Many years and studies later we can say that whether or not any treponemes are visible in the patient, penicillin, except when given appropriate dose very early in the course of the disease, is not an effective and permanent cure.

«Since the late nineteenth century the Wassermann blood test has often been touted as the best diagnostic test for syphilis»

Some physicians still insist that penicillin and strong immune systems definitively eliminate this disease, while others claim that treponemes «hide» in tissues inaccessible to antibiotics. Some speculate that tertiary syphilis occurs when the syphilis treponemes finally manage to spread, after decades of invisible stealth, and penetrate the blood-brain barrier. Alas, most physicians and syphilis scholars (and scientists such as I) simply don’t known the relationship between Treponema pallidum, syphilis symptoms, the immune response, secondary infection, sexual behavior and the putative cures.

Spirochetes, microscopic corkscrews

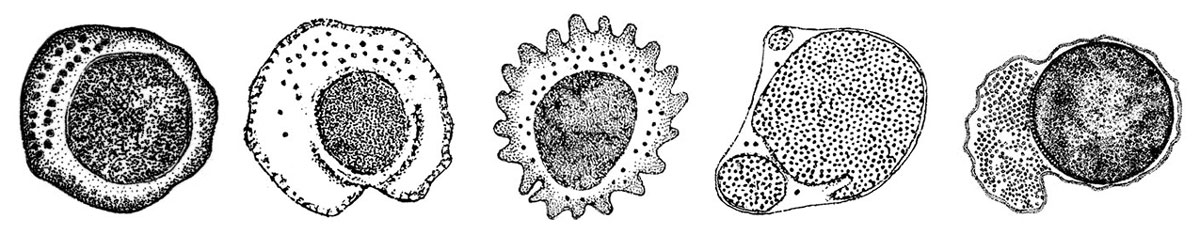

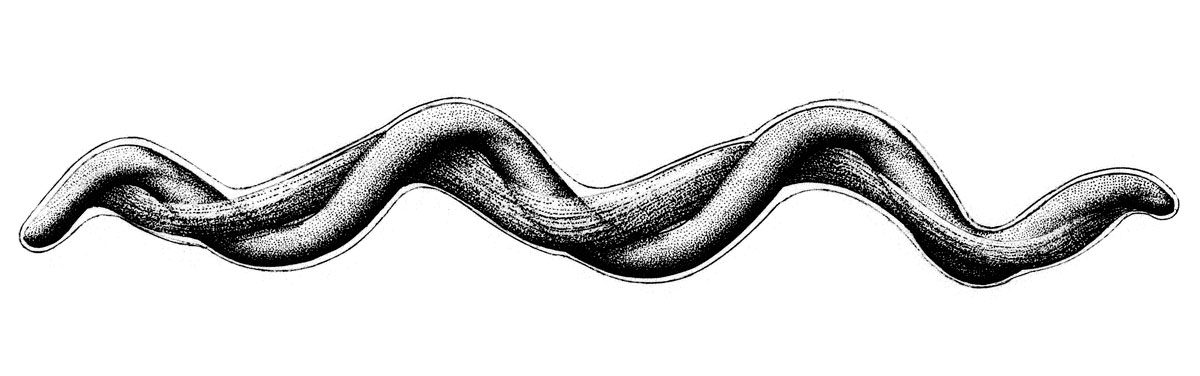

Syphilis symptoms are caused by venereal infection with a spirochete bacterium called Treponema pallidum. The treponeme family of spirochetes consists of corkscrew-shaped bacteria, all of which swim and grow in animal tissue. The bacteria flagella, encased within an outer membrane, are inside the cell. Spirochetes, like other «gram positive» bacteria (for their response to a type of stain) have two cell membranes (the inner and the outer membrane), which are separated by a space (periplasmic space) where the flagella rotate. Smaller spirochetes such as the syphilis treponeme have only two to four such flagella, whereas some giant spirochetes have more than three hundred. The efficient screw-wise motion into genital and other tissue requires this flagella arrangeement.

Treponema pallidum is one freak among a huge diversity. The vast majority of spirochetes live peacefully in mud, swamps and waterlogged soils all over the world. Benign, free-living spirochete relatives of Treponema pallidum are everywhere. They thrive where food is plentiful: lake shores rich in decaying vegetation, marine animal carcasses, hot sulfurous springs, intestines of wood-eating termites and cockroaches, and the human mouth. Most kinds are poisoned by oxygen, which they swim away from to avoid. Very few cause illness. Nevertheless, ticks infected with the Borrelia burgdorferi spirochete of Lyme disease can induce serious arthritis and other enduring symptoms. Yet another spirochete nearly indistinguishable from the Lyme disease Borrelia is a healthy symbiont in the intestines of termites. A treponeme similar to that of syphilis is associated with «yaws», a tropical infection of the skins which can also affect bones and joints. Leptospirosis, a systemic and sometimes fatal infection found usually in fishermen, is due to spirochetes that are carried in the kidney tubules of rats that urinate into nearby water. The fishermen acquire it from fish hook cuts and other skin lesions. And, of course, there is syphilis.

Finally, in 1998, the description of the entire genome of Treponema pallidum, at about 900 genes in total one of the smallest bacterial genomes known, was published. Two other spirochete genomes are known: that of the even smaller Borrelia burgdorferi, with some 1,100 genes, and that of Leptospira, with nearly 5,000 genes. Spirochetes like Leptospira that are capable of life outside the body have at least five times as many genes as the Borrelia spirochete. The leptospires all by themselves internally produce all their necessary components (proteins, lipids, vitamins, and so on), whereas Treponema pallidum does very little by itself; it survives only on rich human tissue as its food. For this reason it is likely that both the Borrelia burgdorferi and the syphilis treponeme lost some four-fifths of their genes as they became obligate parasites.

To identify any bacterium, the microbiologist needs to separate it and grow it by itself, that is, in isolation (axenic or pure cultures). Despite the specific genome knowledge of the single treponemes strain investigated, the routine growth of any Treponema pallidum in isolation (outside the warm, nutritious, mammalian body) has not been achieved. Whether in organic mud or changing human tissue, these spirochetes depend utterly on their immediate environment. Unfortunately, no one has been able to induce round bodies of Treponema pallidum to form an isolation in a test tube and then, in isolation, to test them for viability, that is, for their ability to resume growth in tissue.

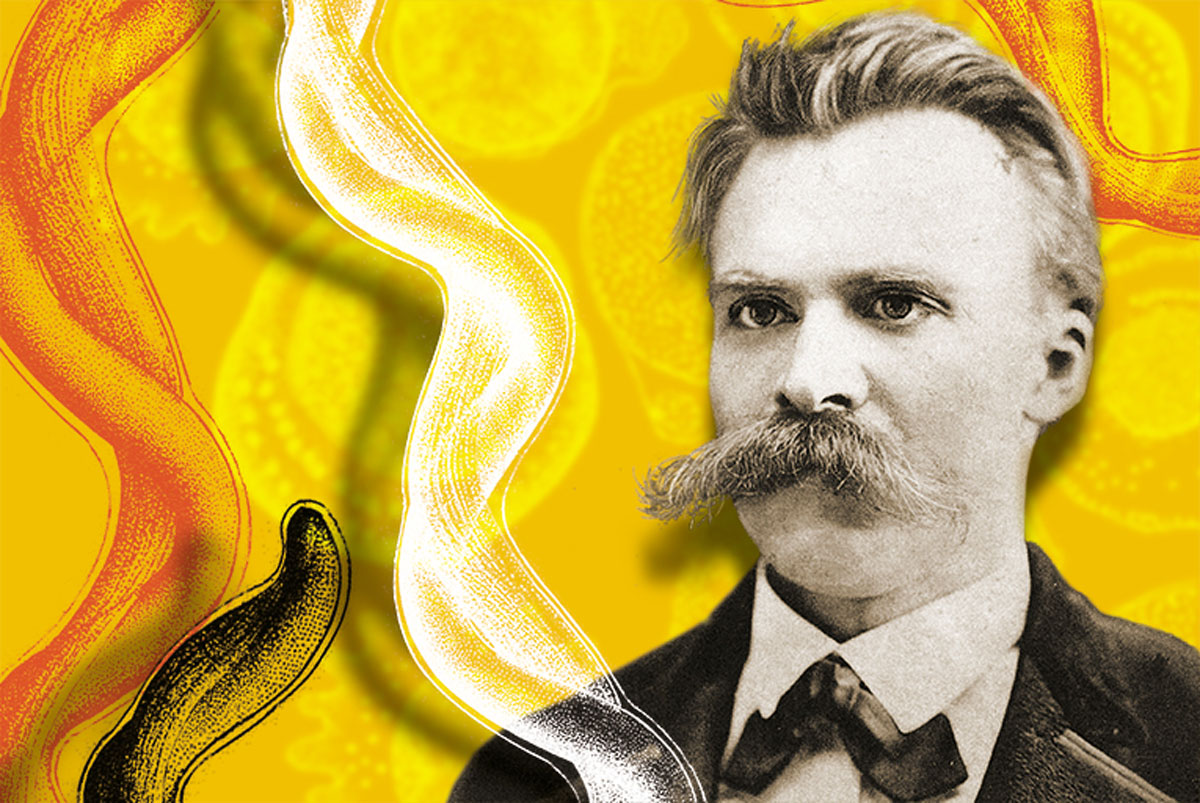

My students and colleagues and I are not experts on any disease bacteria, or even illnesses where symptoms are associated with visible spirochetes. Rather we have been living closely with spirochetes for very different reasons. Our interest is in the possible role these bacteria played in evolution of larger forms of life. Attempts to reconstruct the evolutionary history of the nucleated cell (eukaryotes, the kind that divides by mitosis), had led us to study harmless spirochetes.

I suspect that the mitotic cell of animals, plants and all other nucleated organisms (algae, water molds, ciliates, slime molds, fungi, and some fifty major groups included in the Protoctista kingdom) share a common spirochete ancestor. I believe that with much help from colleagues and students, we will soon be able to show that certain free-swimming spirochetes contributed their lithe, snaky, sneaky bodies to become both the ubiquitous mitotic apparatus and the familiar cilia of all cells that make such moving hairs. Our lab work, coupled with that of other scientists, reveals that certain spirochetes when threatened by death can and do form immobile, shiny round bodies. Furthermore, these round bodies can hide and wait until conditions become favorable enough for growth to resume. Since 1977 a group of scientists and students have been traveling to Laguna Figueroa, near San Quintin, Baja California Norte, Mexico, to study microbial mats. These communities of organisms resemble ancient ones that left fossils in rocks. They are among the best evidence we have for Earth’s oldest life-forms. Many times we brought microbial mat samples back to our lab and left them, as bottles of brightly colored mud, on the windowsill, where photosynthetic bacteria powered the community. On several occasions the bottles were assiduously ignored through semesters of classes and meetings. From time to time we took tiny samples from the bottles and placed them in test tubes under conditions favorable for growth. Spirochetes of different kinds did begin to swim and grow; we suspect they emerged from round bodies after they were put into fresh, clean, abundant liquid food. These spirochetes, mostly unidentified, persisted live but hiding in these bottles and jars for at least ten years.

Today, in our lab at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, we study another microbial community sample collected at Eel Pond, Woods Hole, Massachusetts. It is in a 40-liter glass jar to which we add no food and only «rain» (distilled water), but with sunlight as energy source an abundance of life still thrives. Long after no spirochetes were seen in any of these samples we added bits of either wet or dry mud to food and water known to support activities of spirochetes, swimming and growing. Within about a week armies of spirochetes awoke from at least months of slumber.

We have observed and filmed spirochetes rounding up to form inactive bodies from all over the world. Continuation of work on spirochetes led to continued collaboration with two Catalan research groups with muds from the Ebro delta. Professors Ricardo Guerrero, from the University of Barcelona, and Isabel Esteve, from the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona had begun a strong research project. One stake, a stick in the mud in the western part of La Banya, in the southern arrow of the Delta, marks a site on a microbial mat that somehow seems exceptional. Many different fascinating organisms were taken from that place but none as interesting as the large spirochetes we named Spirosymplokos deltaeiberi. Whenever these easy-to-see spirochetes are confronted with harsh conditions such as liquid that does not support their growth, water that is too acid, sugars they cannot digest, or a temperature that is too high, they make round, dormant bodies like those Pillot and nearly all his successors argue are dead.

The spheres of Spirosymplokos deltaiberi we studied look just like the round bodies published by Norwegian microbiologists Oystein and Sverre-Henning Brorson. (They called them cysts.) The Brorsons showed that under unfavorable conditions the Borrelia burgdorferi spirochete of Lyme disease makes round bodies. After weeks of dormancy, no growth, and no sensitivity to antibiotics and other chemical insults, these round bodies revive. At high magnification they look just like those of Spirosymplokos deltaiberi, only smaller. The Borrelia burgdorferi round bodies convert to form swimming spirochetes all at once and begin to grow easily as soon as they are placed into proper liquid food at the right temperature.

«Nietzsche was inoculated in his early twenties. The wily spirochetes, many as dormant round bodies, had been living in his tissues for over thirty years.»

The Brorsons confirmed what we suspected: spirochete round bodies, like the spheres of Spirosymplokos deltaiberi, are fully alive. Either mixed up with other mud organisms or growing by themselves in isolation, just supply them with what they need to grow and within minutes they revert into swimming, active, feeding corkscrew spirochetes. Armies of them awake from months of slumber. This is the ancient secret of spirochete success: persistence via round bodies.

Nietzsche’s brain on January 3 acted like transfer of microbial-mat spirochetes into new, fresh food. Our interpretation is that they transformed from dormant round bodies to the swimming corkscrews in a very short time. Deborah Hayden, however, is also correct. Nietzsche was inoculated in his early twenties, as his longstanding condition was confirmed both by the physician’s diagnostic on the medical record and, at his death, by pox scars on his private parts. The wily spirochetes, many as dormant round bodies, had been living in his tissues for over thirty years. But on January 3rd in Turin hungry armies of revived spirochetes insinuated themselves into his brain tissue; the consequence was descent of Nietzsche the genius into Nietzsche the madman in less than one day.

NOTES

1. Spirochetes are corkscrew-shaped bacteria that move in a screw-wise motion. (Return to text)