Cinema as spectacle is addressed to the public with diverse purposes, such as entertaining, indoctrinating, distracting or educating, among others. While some films seem to be designed to obtain the maximum benefit, others become a piece of art which becomes part of the history of cinema. Very frequently these purposes are mixed up, as film genres themselves do, making it difficult to classify films under a single label.

Since its beginnings, cinema has shown all sorts of professionals, although police officers, detectives, lawyers, teachers and doctors have been among the most recurrent. In the context of illness, the figure of the doctor is usually associated with that of a nurse (Cano and Rofes, 2014; Gordon and Johnson, 2004). From this fact is derived the purpose of this article: to explore the treatment that the seventh art has given to the nursing profession. For this purpose I will focus on the role of nurses who have a leading role in three films: In love and war (1996) by Richard Attenborough; Wit (2001) by Mike Nichols; and The death of Mr. Lazarescu (2005) by Cristi Puiu.

«The films In love and war, Wit and The death of Mr. Lazarescu review the role of nurses»

These three titles that look over the evolution of the role of the nurse from the first half of the twentieth century to the first quarter of the twenty-first century. In the film In love and war, the main character acts in a scenario that recreates the conditions and resources of medicine before the era of antibiotics. She takes care of wounded soldiers and follows orders from the head nurse and a military doctor. In Wit we see an oncology nurse working with the techniques and resources of a pioneering medical research hospital where her attitude towards a terminal patient humanizes the scientific evidence of the protocols and clinical guidelines, which are so valuable in the second half of the twentieth century. In The death of Mr. Lazarescu we find a versatile nurse who, in the course of an emergency, takes care of patient in his own home. The film shows the effort of a professional to overcome bureaucratic obstacles and the indolence of a healthcare system in crisis, which we could place in the first quarter of the twenty-first century.

The differences between the three feature films, besides those of the time of the action, are also observed in the sex of the patients, two men and one woman, and at the end of the story: one survives, the woman dies and in the third, it is left unknown. Naturally, coincidences or common topics can be identified: in all titles, the co-stars are competent nurses who take care of patients to whom physical pain is added to their loneliness and fear of losing self-sufficiency. In all cases, the main characters interact with other health professionals: in a complicit way with their colleagues and in confrontation with the doctors (Icart, Delgado & De la Cueva, 2015). This aspect makes it clear that the relationship between all of them is complex, a matter which is not concealed in any of the chosen titles.

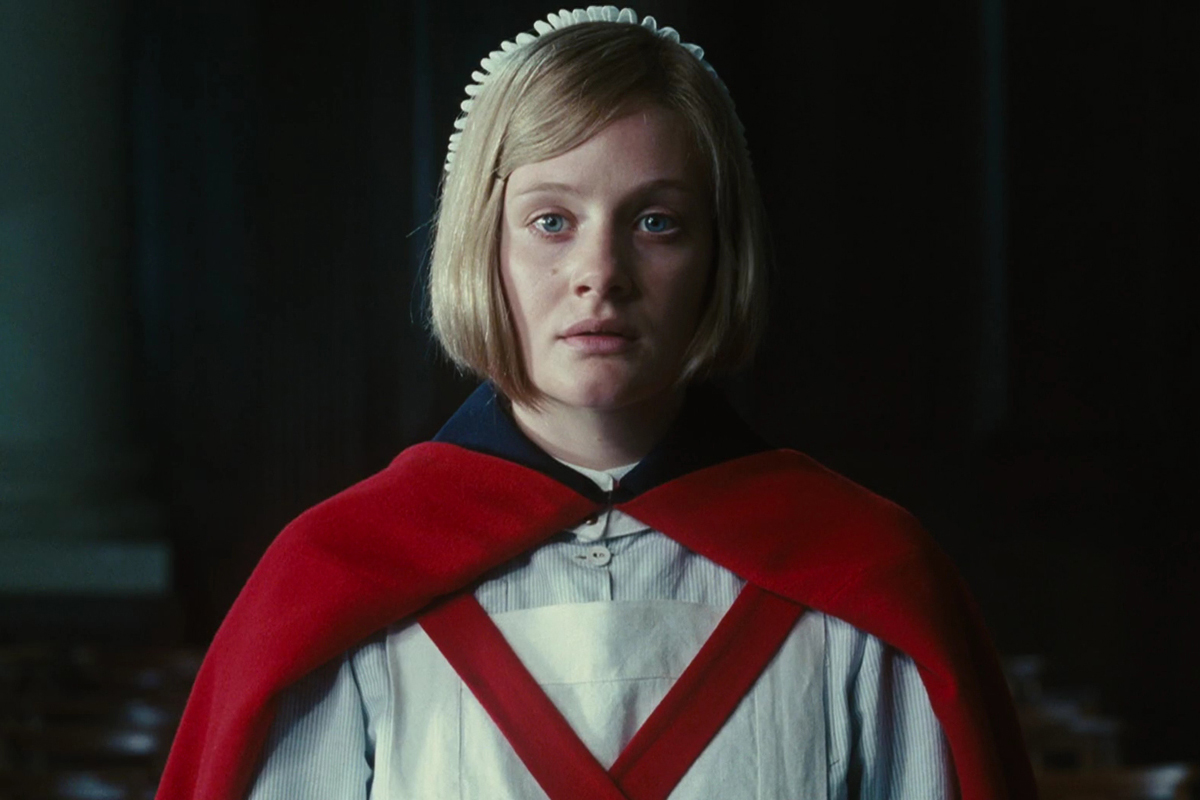

Portrait of Agnes von Kurowsky dressed in the uniform of the Red Cross. The photograph was taken in 1918 during the First World War in Milan (Italy). After his meeting with Ernest Hemingway, Von Kurowsky continued to work as a nurse, first in Haiti and later in the blood bank of New York during World War II. / Image: Ernest Hemingway Collection. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum in Boston.

Agnes von Kurowsky: The nurse who made Ernest Hemingway fall in love

The relationship of the North American nurse Agnes von Kurowsky (1892-1984) with Ernest Hemingway (1899-1961) inspired the novel Hemingway in love and war: the lost diary of Agnes von Kurowsky (Villard and Nagel, 1989). The book was the base of the script for In love and war, which narrates the encounter and the brief love relationship between Agnes and the young Hemingway, who years later would become one of the referents of American literature of the twentieth century.

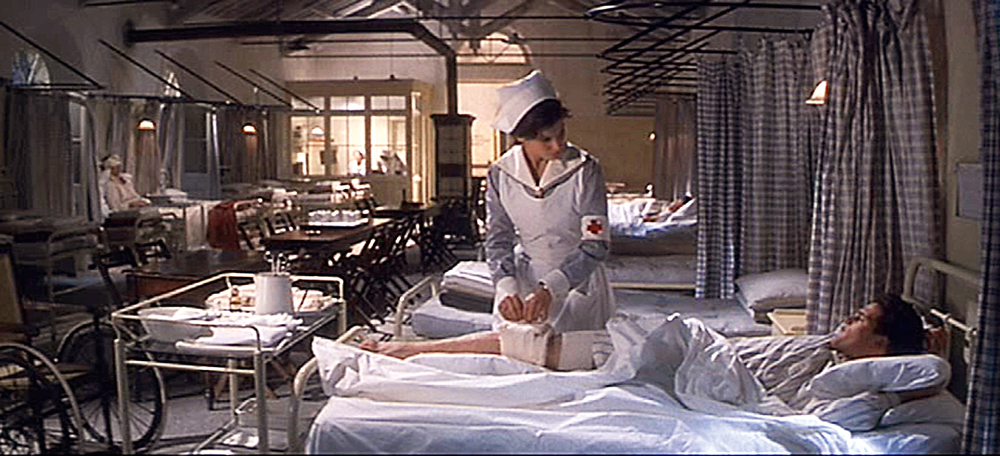

The film starts with the arrival of a group of American Red Cross nurses to the region of Parma (Northern Italy) at the end of World War I. The group is received by the head nurse, Katherine de Long, who reminds them about the prohibition of fraternizing with the wounded: young Italians fighting against the coalition of central empires (Ottoman Empire, Austro-Hungarian Empire, Germany and Kingdom of Bulgaria) facing the Triple Entente (Britain, France, Russia), which was joined by Italy in 1915 and the USA in 1917.

Among the nurses arrived to the hospital of Parma stands out Agnes Von Kurowsky, a twenty-six-year-old woman who has just ended a love relationship, a story she will repeat with Hemingway, an eighteen-year-old journalist whom she affectionately calls «Erni».

Von Kurowsky is a nurse who acts in a warlike context and who has initiative, like when she applies, without a medical order, the Dakin’s solution (sodium hypochlorite buffered) to the wound Hemingway received while evacuating an injured soldier. Possibly, this solution used as a bactericide prevented the amputation of the writer’s right limb. The nurse’s courage will make the military doctor, who is determined to amputate and with whom she evidences her disagreement, finally ask her to collaborate with him to build a hospital on the rubble of an old convent, an offer she will reject (as well as his marriage proposal).

Another example of nurse in warlike cinema with a main role is Evelyn Johnson in Pearl Harbor, directed by Michael Bay in 2001, who organizes the sifting of the wounded soldiers who, after the bombardment of Japanese air forces, arrive en masse at the gates of the military hospital. Johnson uses her ingenuity to mark with lipstick soldiers who have already received morphine and transmits serenity and order to the team that has to act in a situation of maximum tension.

Other warlike films in which nurses have a main role dedicating all their efforts and knowledge to the care of wounded soldiers are: So Proudly We Hail! (1943) by Mark Sandrich, or Atonement (2007) by Joe Wright. However, in general, they are given a secondary role that ends up making them another prop of the story. Their presence is used to make the hero’s suffering more plausible, and less solitary, or they are the sentimental companions of the true protagonists, as is the case of the nurses of The last days of Patton (1986) by Delbert Mann, Born on the fourth of July (1989) by Oliver Stone, and Forrest Gump (1994) by Robert Zemeckis, among many others.

«The main characters interact with other health professionals: in a complicit way with colleagues and in confrontation with doctors»

A feature that is repeated in these films is that the nurses are young, beautiful, aligned with the «good ones» and wear impeccable uniforms until they are stained with the blood of events typical of field hospitals, trenches or the battlefield.

In love and war recreates an episode from the life of Agnes von Kurowsky, who worked as a librarian before graduating as a nurse at Bellevue Hospital in New York. Agnes broke her marriage commitment to Hemingway by claiming she was to get married to an Italian officer instead, something that never happened. However, she married twice and was always committed to her profession, first serving in the Red Cross in Northern Italy (scenario of In love and war), then in Haiti and, during World War II, in the blood bank of New York. She died at the age of 92 and is buried in the cemetery of the American Army in Washington, D.C.

Ernest Hemingway won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1954. It seems that his relationship with Agnes influenced his following relationships, as he married four times, the first time with a woman eight years older. Agnes would have inspired the character of the nurse Catherine Barkey, who, in the novel Farewell to arms (1929), falls in love with an ambulance driver. With the same title, Farewell to arms, two films were made, directed by Frank Borzage in 1932 and by Charles Vidor in 1957.

Susie Monahan: The compassionate nurse

The evolution of the nursing profession is evident in films like Wit, directed by Mike Nichols in 2001. Here we find nurse Susie Monahan, who accompanies a woman suffering from stage IV of an ovarian cancer in the last days of her life. The script is based on the theatrical piece Wit by Margaret Edson, who won the Pulitzer Prize in 1999 (Larson, 2015).

In Wit, a brilliant professor of English literature, Doctor of Philosophy Vivian Bearing, 48 years old, an expert in seventeenth century poems, is diagnosed and treated for cancer during eight months. At the beginning of the process the protagonist uses her ingenuity and sarcasm in an environment, the hospital, of which she ignores everything.

She will spend the last few months in the aseptic coldness of a high-level hospital, pioneer in medical research, where she will be subjected to an experimental treatment of unknown efficacy. Susie Monahan, an Afro-American nurse in her thirties, will help the patient to cope with the uncertainty and fear that invades her as the end approaches. We do not know any details about Monahan’s persona life, but her expertise on oncological care is evident: she performs procedures (measuring liquids, taking vital signs, administering drugs, preparing material, etc.) while humanizing the relationship with the patient.

Her humane bedside manner makes her different from other professionals who mechanically perform diagnostic tests and gynecological explorations, while researching new treatments in Vivian’s body at the same time. Thus, Monahan’s performance contrasts with that of doctor Kelekian, a renowned oncologist, and with that of the young Posner, a resident determined to make merits; curiously, the latter had been a pupil of Professor Bearing, whom he remembers for his excellence and rigour in the study of the poet John Donne (1572-1631), famous for his verses on death.

In the hospital, Vivian Bearing meditates on the difference between the poetic abstraction of death and experiencing it, finally recognizing that the time has come to abandon academic arrogance and admit that in order to face it, other resources such as those offered by Monahan are needed. The nurse helps her adapt to the loss of autonomy and control over vital functions, lets her know her availability («Call me when you need me») and that she will take care of Vivian until the end. However, most of all, she gives her tools to feel that she has control over the events: for instance, deciding not to be resuscitated. In this regard, she informs her about the options available in the event of cardiac arrest: resuscitation and transfer to intensive care until it is stabilised or not applying the resuscitation protocol (Bayes, 2006).

Susie’s empathy is evident in the affectionate tone of her voice and the treatment of a relationship that begins with a «Mrs. Bearing», to the more personal and intimate «Vivian». She uses kind words during the gynaecological examination and sits next to her patient offering her an ice cream to alleviate the stinging of the mucositis caused by chemotherapy.

But Monahan is also assertive, she empowers herself by defending Vivian’s rights, who has refused to be resuscitated, and ends up pushing the resident doctor who wants to resuscitate Professor Bearing when she is dead. It is a scene that shows the contrast between the ability to face the end of life and the inexperience, arrogant and frightened, of those who do not acknowledge the limits of medicine (Cambra, 2017). Susie prevents therapeutic brutality to continue and when she manages to make common sense prevail over the stubbornness of the resuscitation team, she covers the naked body of the protagonist and manages to alleviate the pain and impotence that has been invading the spectator.

The proactive role of the nurse that goes beyond the uncritical compliance of medical orders is also showed in the films Johnny got his gun (1971) by Dalton Trumbo, or The English patient (1996) by Anthony Minghella. In the first case, a nurse, whose name we do not know, will be the only human being capable of understanding the despair of Johnny, the young soldier who has been left isolated and cut off from the world by multiple wounds. In the second film, Hanna will put an end to the suffering of count László Ede Almásy, with burns all over his body, for whom life has become a painful memory.

Mioara Avram: The nurse against a sick health system

The death of Mr. Lazarescu (2005) by Cristi Puiu, is surely the film that best reviews the daily life of a twenty-first century nurse who works in our environment. Gone are the religious, sacrificed and vocational nurses of Black narcissus (1947) by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger; Ana (1951) by Alberto Lattuada; The sins of Rachel Cade (1956) by Gordon Douglas, or The nun’s story (1959) by Fred Zinnemann. Or the heroines of the warlike genre such as Nurse Edith Cavell (1939) and Dawn (1928), both by Herbert Wilcox, or So Proudly we hail! (1943) by Mark Sandrich, among others.

«The death of Mr. Lazarescu is surely the film that best reviews the daily life of a twenty-first century nurse who works in our environment»

In The death of Mr. Lazarescu, the nurse Mioara Avran is a woman in her fifties who has been working for sixteen years in the emergency service of Bucharest (Romania). Avram is the one who accompanies a poor, alcoholic old man through the four hospitals he will visit in one night (Icart-Isern and Icart-Isern, 2016). The journey begins when Avram arrives at the home of a man who lives with his three cats. Avram observes him, explores him, records his anamnesis, takes his blood pressure and temperature. Finally, after giving him an analgesic by intravenous route and seeing that the pain continues, she decides to transfer the old man to a hospital.

The film shows the relationship of the nurse with members of the health staff: the driver of the ambulance as well as colleagues and eight doctors from different specialties who diagnose and treat Lazarescu. All the interactions serve to know more about Mioara: for example, that she has an eighteen-year-old daughter and a twenty-six-year-old son, father of a girl and whom she criticizes for not getting married. She is a skilled professional in the management of a difficult patient and also knows the details of a health system in which personal relationships are worth more than the urgency of having an essential test to initiate treatment.

An arrogant behaviour full of contempt is constant on the part of the doctors; a treatment that is aggressive towards the patient, like the one dispensed by Dr. Ardelean: «Get him out of my sight. Send him home, what are you waiting for?». Or the one by Dr. Bresalus: «Considering the state og Mr. Lazarescu, you could have injected him with compote. He is dying, poor man». No less contemptuous is Dr. Miriaca when he addresses Mioara: «[…] if you want, you can stay, but please keep your mouth shut […]. Nurse, shut up at once». Mioara shows an extraordinary patience, she defends herself and the patient, whose neglected appearance displeases the doctors.

The complaints of the nurses of the last hospital to which Mioara and Mr. Lazarescu arrive are, probably, that many professionals in our centres would express: «At the last minute always comes some drug addict, drunk or wounded, just in the change of shift»; situations and experiences that Mioara summarizes: «What a horror, two more days like this and in the end you will have to admit me». In spite of her tiredness, this professional is an example of the generous and honest effort of those who want to restore the condition of human being to a patient in need of understanding and welcome, and brings us into the reality of an oversaturated health system in which bureaucracy makes the resolution of health problems heavier (Crespi, 2012).

As The death of Mr. Lazarescu, other films also show nurses working in different contexts from the usual hospitals, such as the community (The World According to Garp, 1982 by George Roy Hill; Miss Evers’ Boys, 1997 by Joseph Sargent), school (A Map of the World, 1999 by Scott Elliott), home (Passion Fish, 1992 by John Sayles), or in places as particular as an oil rig (The Secret Life of Words, 2005 by Isabel Coixet).

In this text we have omitted porn, gore or B films because we consider that they do not represent the reality of the nursing profession. The stance taken by nursing professionals with regard to these films is diverse. On the one hand, one might think that to criticise certain films is to forget that cinema is a fiction that seeks to capture and maintain attention, even if it is at the cost of mocking or belittling the protagonists, and for this reason it would make no sense to waste time analysing and discussing titles that devalue the image of the nursing profession. On the other hand, it is possible to replay that certain images that denigrate professionals must be criticized and denounced, whatever the cinematographic genre.

The examples chosen are a representative sample of how the figure of the nurse has evolved in the cinema through the last decades: from the beautiful and young nurse that make patients and doctors fall in love of her, to the professional that shows empathy, empowers the patient and keeps a committed attitude in people-centred healthcare.

Bayes, R. (2006). Wit. En A. Casado, & W. Astudillo (Eds.), Cine y medicina en el final de la vida (pp. 121–130). San Sebastián: Sociedad Vasca de Cuidados Paliativos.

Cambra, I. (2017). La autonomía al final de la vida. In I. Cambra, & J. J. Michel (Eds.), House y la cuestión de la verdad (pp. 105-108). Buenos Aires: Letra viva.

Cano, P. L., & Rofes, S. (2014). Sobre médicos, enfermeras y enfermedades en el cine. Barcelona: LaEditorial.es.

Crespi, R. (2012). Ficción y reflexión: Comentario al film La muerte del Sr. Lazarescu. Retrieved 15 October 2017 from http://roycrespi.blogspot.com.es/2012/03/ficcion-y-reflexion-comentario-al-film.html

Gordon, S., & Johnson, R. (2004). How Hollywood portrays nurses. Report from the front row. Retrieved 15 October 2017 from http://www.truthaboutnursing.org/research/orig/gordon/gordon_johnson_revolution.pdf

Icart, M. T., Delgado, P., & De la Cueva, L. (2015). Las enfermeras en el cine. Imágenes de una profesión. Barcelona: Edicions Universitat de Barcelona.

Icart-Isern, M. T., & Icart-Isern, M. C. (2016). La muerte del Sr. Lazarescu. Moartea domnului Lazarescu (2005): efectos de la recesión económica en el sistema sanitario. Revista de Medicina y Cine, 12(1), 3–11.

Larson, S.A. (2015). Wit – A film review, analysis and interview with playwright Margaret Edson. The Journal of Humanities in Rehabilitation. Retrieved October 22, 2017 from https://scholarblogs.emory.edu/journalofhumanitiesinrehabilitation/files/2015/08/Wit.pdf

Villard, H. S., & Nagel, J. (1989). Hemingway in love and war. The lost diary of Agnes von Kurowsky. New York: Northeastern University Press.